"After completing TAFE in 2005 I applied for many junior positions where no experience in sales was needed – even though I had worked for two years as a junior sales clerk. I didn’t receive any calls so I decided to legally change my name to Gabriella Hannah. I applied for the same jobs and got a call 30 minutes later."

∼Gabriella Hannah, formerly Ragda Ali, Sydney.

---

A few years ago, I heard about an experiment in which Australian researchers sent out a bunch of identical job applications, differing only in the ethnicity of the applicants' names. The goal was to see how those with non-Anglo names would fare compared to those with Anglo Saxon-sounding names. The study found applications with non-Anglo names were significantly less likely to receive a call back from potential employers.

As someone from a non-Anglo background who has experienced plenty of racism in Australia, I was intrigued and wanted to read the actual study. However, cursory searches on the Internet failed to locate it (the Sydney Morning Herald seems to have been the only major media outlet that bothered to report the study). It was not until recently, while searching for another paper, that I stumbled across it.

To save you hours of fruitless web searching, the paper can be freely accessed here:

Does Ethnic Discrimination Vary Across Minority Groups? Evidence from a Field Experiment

So what did the experiment involve?

Well, in 2007, Australian National University researchers Alison Booth, Andrew Leigh and Elena Vargonova randomly submitted over 4,000 fictional applications for entry-level jobs (hospitality, data entry, customer service, sales) advertised on the internet. The applications were identical, save for the racial origin of the supposed applicants' names.

The experiment involved three Australian cities: Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney.

Overall, applicants with Chinese names fared the worst, having only a one-in-five chance of getting asked in for interviews, compared to applicants with Anglo-Saxon names whose chances exceeded one-in-three.

Based on the results, a Chinese-named applicant would need to put in 68 per cent more applications than an Anglo-named applicant to get the same number of calls back. A Middle Eastern-named applicant needed 64 per cent more, an indigenous-named applicant 35 per cent more and an Italian-named applicant 12 per cent more.

There were some differences between cities. Sydney was the most discriminatory towards Chinese and Middle Eastern names, but more accepting of indigenous names. Brisbane was the most discriminatory towards Italian names.

Melbourne, meanwhile, provided the only exception to the rule. In that city, Italian-named applicants actually had a 7% greater likelihood of getting a call back. However, the difference was not statistically significant.

"But what it does allow you to say," said Dr. Leigh, "is that there is no statistically discernible discrimination against Italian names in Melbourne. They are as well-regarded as Anglo names.

"This could be because Melbourne has a higher share of Italians than other Australian cities, and has had for a long time. Discrimination tends to be higher when you have a recent influx of arrivals, as Sydney has from China and the Middle East.

"Or it could be because many of the jobs we pretended to apply for were waiter and waitressing positions in bistros, bars, cafes and restaurants."

On a personal level, in all my years of visiting and then living in Melbourne, no-one ever called me a racist epithet. The same, sadly, cannot be said for Adelaide, Sydney and the Gold Coast (which sits around 70km south of Brisbane). Melbourne is by far the most cosmopolitan of Australian cities, with significant Greek and Italian populations.

Asked whether the study had found that Australian employers were racist, Dr Leigh said it was clear they discriminated on the basis of the racial origin of applicants' names. "There is no other reasonable interpretation of our results," he said.

The fake applications had made clear that the supposed job-seekers had completed secondary schooling in Australia, making it unlikely the employers assumed the non-Anglo applicants could not speak English.

Employers were given the choice to respond to applications via email or phone. The researchers set up phone lines with an answering machine, all of which had a message left by a person with a regular Australian accent. The researchers did this because applicants were supposed to differ only by their racial origin, not by their English language skills, and they wanted to guard against the possibility of a prospective interviewer simply hanging up if they heard a foreign-sounding voice. If the researchers had used voicemail accents to match the ethnicity of the names, then it's quite possible the difference in call back rates would have been even more pronounced.

If you're looking for work in Australia and have an accent then, regrettably, it might be wise to have an Australian-sounding acquaintance record your voice message for you.

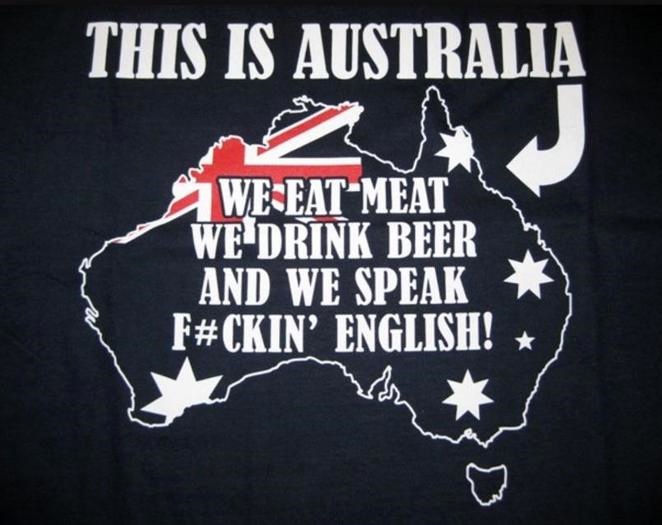

And we take lots of f#ckin' drugs! (Australia has the highest per capita rate of illicit drug use in the world). Meanwhile, in many other parts of the world, people eat meat, drink beer and can often speak English in addition to their native language.

And we take lots of f#ckin' drugs! (Australia has the highest per capita rate of illicit drug use in the world). Meanwhile, in many other parts of the world, people eat meat, drink beer and can often speak English in addition to their native language.

Other Countries

In their paper, Leigh et al also tabulated the results of similar studies from around the world. Of those studies conducted during the same era (specifically, between 2001 and 2008), the results were as follows:

USA: To get a call back, African-Americans needed to submit 1.5 applications for every application submitted by someone with an Anglo-Saxon name.

Canada: Indian, Chinese and Pakistani applicants had to submit 1.31, 1.46 and 1.44 applications, respectively.

Ireland: Africans, Asians and Germans had to submit 2.44, 1.80 and 2.07 applications compared to Irish applicants.

Sweden: Middle Eastern and Arabic/African applicants needed to submit 1.50 and 1.80 applications, respectively.

A series of studies conducted in the UK between 1969 and 1997 also showed widespread employer discrimination, however direct comparison with the above-mentioned results is precluded by the differing time periods.