Something real strange happened in the eighties.

No, I’m not referring to the proliferation of fluorescent clothing and polished cotton disco pants. Or the popularity of applying eye-liner before a night out on the town – among heterosexual males.

Nor am I referring to the beyond-boofy hairdos of the era that sported fringes so large they gave more shade than a Stratco verandah.

Nope, I couldn’t care less about any of those fads, because their lifespans were relatively short. But something else arose in the eighties whose global impact was to be far more severe and far longer lasting.

That something was low-fat mania.

Due to the stunning realization by health authorities and certain authors that carbohydrates yielded around 4 calories per gram, while fats supplied around 9 calories per gram (something actually known to scientists for decades prior), these busy-body authorities decided – during what must have been a very drunken brainstorming session – to start urging the world to eat less fat in order to prevent obesity.

This overly simplistic and, quite frankly, patently stupid strategy was based on the premise that human beings –not exactly known for their temperance and moderate behaviour – would obediently lower their fat intake, and make no attempt whatsoever to compensate for the decreased caloric intake and decreased satiety by consuming greater amounts of alternative macronutrients.

But they did. And how. To make up for the lack of taste and satiety imparted from the now departed dietary fat, they not only began adding more sugar to their cereal and squeezing more syrup onto their pancakes, they began consuming a far higher quantity of carbohydrates overall. In fact, they just couldn’t get enough of those sweet, delectable carbohydrates, so to squelch their between-meal carb-cravings, they began guzzling down ever-greater amounts of sugar-laden juices and soft drinks.

And that was the folks who actually lowered their fat intake. Many did not, but consumed extra carbohydrate anyhow, convinced by all the “fat-makes-you-fat” hysteria that extra carbohydrate calories were somehow inconsequential.

Amidst this burping, flatulent orgy of carb-binging, food manufacturers quickly realized a golden opportunity was staring them in the face. They began pumping out low-fat, carbohydrate- and sugar-rich foods en masse, and a multi-squillion dollar industry was born.

All around the world, people were gorging themselves on the kind of caloric and carbohydrate intakes that would do many professional athletes proud.

There was just one wee problem: Most of these people weren’t professional athletes. In fact, most didn’t even exercise, let alone compete in triathlons. The 1980s, in effect, was the era in which normal-weight sedentary people all around the world began doing what anyone commencing regular strenuous training in a glycogen-dependent sport should do: increase their caloric and carbohydrate intake to cover the increased energy demands imposed by their new training regimen.

They just left out the training regimen. Sedentary housewives and businessmen were eating more carbs and calories, but they remained sedentary housewives and businessmen.

The result: Planet Earth promptly became home to the fattest and most diabetic population this world has ever known.

The moral of the story? Excess calories are real and have consequences, whether they come from protein, fat, or carbohydrates. If you are going to emulate the dietary macronutrient composition of a pro athlete, then you better damn well train like one.

Stupid Is as Stupid Does

The story doesn’t end there folks. Oh nooooo, not by a long shot. Because in the late 90s, something else really strange happened.

No, I’m not talking about the cigar-based antics of a certain ex-President and his chubby intern, the screwballs who blamed Columbine on Marilyn Manson albums, or the share price of Pets.com.

No, I’m referring to the rise of a creature every bit as deluded and simple-minded as the authorities who convinced the world to go low-fat.

The name of this Do-Do-like creature?

The low-carb guru.

The low-carb guru was typically a cardiologist or family physician who realized far greater fame and fortune was to be had in becoming a “diet doctor” than prescribing warfarin and treating coughing, wheezing, carbuncled Medicare recipients. The low-carb guru usually looked like he himself could sorely use some good fat loss advice, but this hardly mattered to a population beleaguered with obesity and diabetes and desperate for the next novel-sounding quick-fix.

If it was a novel magic bullet the population wanted, then the low-carb gurus were more than happy to give it to them. So in response to the myopic and simple-minded war on fat, they presented their revolutionary solution:

A myopic and simple-minded war on carbohydrate.

Bloody brilliant!

Well, not really. Truth be told, it was bloody moronic. Some people lost weight on the low-carb diets by unwittingly lowering their caloric intake, just as some folks lost weight on the low-fat diet when they were able to refrain from consuming extra carbohydrates.

But, just like many folks in the low-fat era believed carbohydrate calories were without consequence, many of the newly-converted low-carb devotees became convinced that fat and protein calories were inconsequential. Only carbohydrates needed to be restricted, they were told, because carbohydrates caused insulin release, which by some magic voodoo process caused fat gain.

I say “voodoo” because real science showed that in real life humans, isocaloric high- and low-fat diets cause no meaningful difference in metabolic rate (when there is a slight increase in metabolic rate, it is almost invariably seen with high-carb meals and diets) and no meaningful difference in de novo lipogensis (creation of new fat). Tightly controlled metabolic ward studies in which the likelihood of non-compliance was greatly reduced, and in some instances made virtually impossible, repeatedly showed no difference in fat-derived weight loss between isocaloric low- and high-carb diets.

This of course, mattered little to the low-carb gurus and their gullible followers. The gurus simply ignored the tightly controlled human dietary research and instead cited ad nauseum very short-term studies in which intravenous insulin infusions, or administration of insulin to adipose cells in petri dishes, caused suppression of lipolysis and stimulation of lipogenesis. From these largely irrelevant studies they built a virtual religion whose fundamental tenet was “Carbs raise insulin, insulin makes you fat”.

To give the impression that these unnatural experiments actually had relevance in humans, they cited the half of free-living studies comparing low- and high-carb diets that showed greater weight loss in the former. The remaining half that found no difference were simply ignored, as of course were the multitude of metabolic ward studies that completely failed to show any difference.

Bah, impartiality and conflicting evidence…who needs it?

The poor schmucks who soaked up this bullshit, that’s who.

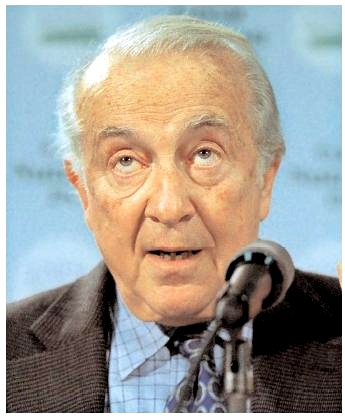

The nineties: When serious athletes started taking nutrition advice from blokes who looked like this.

The nineties: When serious athletes started taking nutrition advice from blokes who looked like this.

Thanks to their belief in the nonsensical metabolic advantage spewed forth by the high priests of low-carb, millions of low-carb devotees endured constipation, bad breath, lethargy, and a socially awkward diet in the hope of weight loss that never materialized. They slashed their carb intake even further, pissed on their Ketostix even more fervently (“turn purple, you bastard! PURPLE dammit!!”), but still no weight loss aside from the 2 or 3 kilos of electrolyte-flushing water loss they experienced at the start of their low-carb misadventure.

Low-carbing turned out to be a big disappointment. Nary a dent was made in obesity rates, and as Generation Quick-Fix waddled off in search of the next overhyped load of bollocks, the lucrative low-carb empire collapsed. Atkins Nutritionals went bust, the follow-up to the best-seller Protein Power bombed, and unwanted copies of Dr Atkins New Diet Revolution, The South Beach Diet, and Protein Power started appearing on shelves of charity shops faster than you could say “Low-carb pasta tastes like soggy sawdust – only worse”.

“Good riddance!” exclaimed a disillusioned and fat-as-ever population.

However, they spoke too soon, for not all the low-carb demons had been exorcised. Along with the rise of the low-carb gurus beginning in the late 90s, something else really bizarre happened.

It was this: swayed by the low-carb hypebole, many highly active strength and endurance athletes started eating low-carb diets, despite the fact that a literal mountain of research has shown that high-carbohydrate diets were the far superior choice for glycolytic activities.

Intelligently applied non-ketogenic low-carb diets (in other words, not the kind recommended by the low-carb gurus) were actually a viable short-term choice for diabetic and totally sedentary folks (however, the negative effects of keto and non-keto low-carb diets on T3 levels makes them a questionable long-term option). But for athletic folks, they were a terrible choice, period.

So while in the eighties sedentary folks started eating diets with macronutrient and caloric profiles more akin to those of serious athletes, the opposite was now occurring: Many serious athletes were consuming diets with a carbohydrate content suitable only for diabetics and inactive people.

And they were suffering for it.

Don’t Run a High-Octane Machine on Low-Octane Fuel

Activities like boxing, cycling, mixed martial arts, running and even high volume weight training are dependent on a steady supply of carbohydrate to replace the muscle glycogen that would otherwise be exhausted during these glucose-dependent activities. As research has repeatedly shown, low-carbohydrate diets are simply incapable of maintaining optimal glycogen levels and vastly inferior to high-carb diets when it comes to improving performance.

While those pursuing weight loss were hoodwinked with the “carbohydrate-insulin” hypothesis, athletically-inclined folks were reeled in with an equally unscientific theory known as the “fat adaptation” theory. According to this hypothesis, your performance and mood may suffer during the first week or so of a low-carbohydrate diet (this much is actually true), but after this adaptation phase, your body will become wonderfully adept at running on fat and performance in your chosen sport will skyrocket. You won’t have to worry about glycogen depletion or “hitting the wall”, because your newly fat-adapted body will just keep drawing on body fat to power your workout into the next millennium.

This theory is utter rubbish.

Before I detail the science showing exactly why, let’s take a look at some real life examples of what happens when endurance athletes are suckered by the fat adaptation hogwash. Here’s an email I received from Kevin, an avid marathon runner who attempted an ultra-endurance event after months of low-carbing. He recounts what happened, and it wasn’t a very happy experience:

Hi Anthony,

I've followed you for years going back to the Active Low Carb website, which has banned me. I have The Great Cholesterol Con and The Fat Loss Bible.

Preface: The lowcarb approach to diet is insidious. That the initial weight loss is all water doesn't make much difference to most, including me. But I have a story that explains why I finally quit the lowcarb bull:

I'm a marathon and ultramarathon runner. A couple years ago I ran the Antelope Island 50 mile race. Antelope Island is the largest island in the Great Salt Lake of Utah. Months of diligent lowcarb eating had caused me to lose 20 pounds by race day. Initially I felt I was running slower than my norm but attributed it to the cold. The race was in March and in Utah it tends still be winter-like in March. As the day warmed I tried to increase my pace but still lagged below my normal pace.

The island is a bit over 25 miles long. Runners start at one end, run to the other end then turn around and come back. The island has a small mountain dead-center. The course requires running to the top each way. When I was climbing it for the second time, my energy level was so poor I was unable to run and instead was trying to race-walk. By the time I got back down to level ground I was having leg cramps and shivering from the cold. Runners passing me were wearing shorts and t-shirts so it wasn't that cold. This was around mile-40. By mile-45 the cramps had progressed to my ass, lumbar back, shoulders, triceps and neck. I ultimately finished, dead last among the 200 runners.

But the story doesn't end there. I had put up a tent near the start-finish line the night before the race. I slept in the tent and was first on the course on race day. I'd planned to sleep in the tent after the race rather than make the 6 hour drive home. Crawling into the tent I was shivering from the cold. The shivering aggravated the cramping. I lay in the sleeping bag trying to get warm enough to stop the intense shivering and horrific cramping. Around midnight I couldn't take the it anymore. I crawled out of the tent and crawled to my car. It took several minutes to unlock the door and get myself seated in the passenger seat. Then I turned the heater on full-force. I sipped gatorade all night and the cramping didn't stop til dawn. The entire night was a wide-awake nightmare.

So I learned the hard way. Low carb proponents want to lose weight without controlling their diet. Some, like me, try to get around it with intense exercise. But as the body becomes more efficient it loses less weight through exercise. That's the closest thing to a true metabolic advantage. And it was an advantage during famines, I imagine.

Thanks for continuing the fight, although you won't convince anyone unless they've gone through an ordeal similar to mine.

Kevin

Kevin’s experience is being played out by misguided exercisers the world over. Serious strength and endurance athletes, suffering from an irrational fear of carbohydrate, go to great lengths to avoid the very macronutrient they actually need the most. When their performance inevitably dives, they first attempt to rationalize it away, figuring they’re “having a bad day”, or that it “must be the headwind slowing me down”. After several months of persistent bad days, even when the weather is fine and a nice strong tailwind is blowing, reality starts to sink in. A deeply unsettling feeling that something’s just not right begins dominating their thoughts every waking moment.

That something is a lack of carbohydrate, which causes glycogen depletion, which in turn leaves muscles unable to get the glucose they need to produce ATP, the ultimate cellular fuel source.

I’m intimately familiar with this whole scenario, because I’ve been through it myself. In what now seems like a lifetime ago, when I was far less wiser than what I am now, I figured I’d prove to the world that ketogenic diets could indeed adequately fuel glycolytic activities. I ‘d been following a low-carb diet for several years, and a ketogenic intake for around a year, so the usual objections trotted out in response to clinical studies about lack of fat adaptation did not apply. During the final 18 months or so of finishing my book The Great Cholesterol Con, I had been doing very little bike riding and had been maintaining my strength and fitness on a “skeleton” regimen comprised of weight training and a couple of hours of MMA training on the weekends. After escaping from a suffocating marriage, then finally finishing the book, I decided to reward myself with a brand new Scott CR1, a game-changing machine that at the time was setting new benchmarks in carbon fiber bicycle frame technology.

I bought my new bike and began eagerly hitting the hills. At first, I was able to zip up the hills with little problem. "Ha!", I thought, "who says low-carb ketogenic diets can't power high level physical activity?"

It wasn't long before reality came knocking. Hard. My energy and performance started tanking. My times got slower. And slower. My rides progressively felt harder and harder. It felt like someone was slipping an invisible and increasingly heavier weight vest over my shoulders with each and every ride.

Off the bike, my legs started feeling heavy and tired - classic signs of glycogen depletion. My arms and torso felt fine, indicating that the cycling was tapping into my leg muscles' glycogen stores much faster than what my low-carb diet could replace them. The problem wasn't insufficient calories or fat, as I was eating plenty of both and maintaining my weight.

The final straw came one day as I was riding up a route well known to Melbourne road cyclists as "The Wall". When I was passed by a cyclist with thighs not much bigger than my forearms, I immediately sought to rectify the situation by catching up, slipstreaming, then passing him. But no matter how hard I tried, I simply couldn't catch the guy - it was like someone had ripped out the muscles from my legs and replaced them with lead. There I was, with my speed-skater-like thighs and world-class super-light road bike, being left in the dust by someone with the physical presence of a starvation victim and riding an old Giant. It was at this point that a rising sense of anger and disgust finally overpowered my stubborn denial. I had to face the facts: despite my enthusiasm for ketogenic dieting, it was killing my cycling performance.

The rest, as they say, is history. I began increasing my carbohydrate intake and my performance immediately improved. Nowadays, I average around 400-500 grams of carbohydrate per day, and my ride times have improved to the point where I can power up to Mount Lofty on a heavy-ass steel-framed single-speed significantly faster than what I used to do on the feather-light Scott. My old low-carbing days are now just a distant bad memory, but the sad reality is many active people out there are still plugging along in a mire of substandard performance, waiting for a magical fat-derived performance boost that will simply never arrive.

The moral of the story? If you want to train, perform and look like a serious athlete, you better damn well eat like one. People who perform vigorous exercise have no business eating a diet best suited to diabetics and sedentary soccer mums.

In Part 2, I’ll delve into the sports nutrition research that conclusively shows low-carb diets to be a complete dud when it comes to fuelling high level exercise. We’ll also take a closer look at some athletes who supposedly achieved athletic success following a low-carb diet.

Until then, keep eating your berries and sweet potatoes,

Anthony.

—

Anthony Colpo is an independent researcher, physical conditioning specialist, and author of the groundbreaking books The Fat Loss Bible and The Great Cholesterol Con. For more information, visit TheFatLossBible.net or TheGreatCholesterolCon.com

Copyright © Anthony Colpo.

Disclaimer: All content on this web site is provided for information and education purposes only. Individuals wishing to make changes to their dietary, lifestyle, exercise or medication regimens should do so in conjunction with a competent, knowledgeable and empathetic medical professional. Anyone who chooses to apply the information on this web site does so of their own volition and their own risk. The owner and contributors to this site accept no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any harm, real or imagined, from the use or dissemination of information contained on this site. If these conditions are not agreeable to the reader, he/she is advised to leave this site immediately.