You're already using the world's most popular PED - here's how to optimize its benefits.

1,3,7-trimethylxanthine, more commonly known as caffeine, is one of humankind's oldest drugs. It’s also the most widely used, surpassing alcohol in popularity.

A 2022 survey found over 90% of Americans consume caffeine, with 3 out of 4 consumers doing so daily.

Between 1984 and 2004, caffeine was a banned substance in sports due to its well-established ergogenic (performance-enhancing) effects. Despite scientific evidence for those ergogenic benefits growing ever-stronger, the World Anti-Doping Agency removed caffeine from its list of banned substances, no doubt due to the complications of prohibiting such a ubiquitous dietary ingredient. Caffeine now remains on WADA’s so-called ‘monitoring program’.

So as a substance with acute affects on cognition and alertness, and one whose performance-enhancing effects were confirmed decades ago, this means most people are taking both a stimulant and a PED.

Most people, of course, don’t look like dopers. Most, unfortunately, don’t even look like they exercise.

If you do exercise or compete in athletic events, then caffeine can boost your performance - safely and legally. However, despite decades of research, there still remains significant uncertainty about just what caffeine can do, and how to best use it as an ergogenic.

What doses of caffeine provide an ergogenic benefit? Is more better, or is there an ideal range?

Caffeine is well known to enhance performance in endurance activities like running and cycling, but what about at the gym? Will a shot of caffeine increase your one-rep maximum (1RM) or help you squeeze out more reps on your favorite exercises?

Caffeine enhances short-term performance, but what about long-term use? Will caffeine make you leaner, stronger and fitter over the longer term?

Does the ergogenic impact of caffeine differ between males and females?

Does regular consumption (“habituation”) weaken the ergogenic effects of caffeine?

I’ll address all these questions in coming installments. Today, I want to address another key question, and also issue an important safety warning.

Coffee vs Caffeine, Plus Another White Powder You Should Avoid

Coffee is the world’s most popular source of caffeine. Even in countries like the US, it outranks soft drinks, tea, and energy drinks as the primary caffeine delivery vehicle.

Despite this, most of the research into the ergogenic effects of caffeine has been performed using caffeine anhydrous (dehydrated caffeine), not coffee.

The use of caffeine anhydrous capsules/tablets makes it easier for researchers to ensure study participants receive the desired amount of caffeine. It also eliminates any potential confounding effect of the numerous other compounds in coffee.

Caffeine anhydrous is readily available, most famously as NoDoz tablets.

Overdoses involving caffeine tablets are almost always intentional. However, it is possible to accidentally overdose on caffeine, and the consequences can be catastrophic.

While supplements are most commonly consumed as capsules or tablets, many are also available in powdered form. The powdered versions are typically cheaper on a per-gram basis, and some supplements are more convenient to use in ‘bulk’ form. For example, creatine and branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) are typically taken in multi-gram dosages that would necessitate swallowing a large number of capsules. Far easier to scoop out a teaspoon of powder, mix it in water, and drink it.

There have been times I’ve absentmindedly gulped down a heaped teaspoon of creatine when I thought I was taking BCAAs. Because creatine is a fairly benign substance when taken in non-idiotic amounts, there were no negative repercussions.

Make that mistake with caffeine anhydrous powder - where 1 teaspoon can equal around 28 cups of coffee - and the consequences can be fatal.

If you think I’m presenting a hypothetical scenario that has probably never happened to anyone, think again. The literature is replete with case reports of fatalities and life-threatening emergencies occurring after ingestion of multi-gram amounts of caffeine; some of these involved accidental overdose of powdered caffeine by gym buffs (Jabbar 2013; Eichner 2014; Magdalan 2017; Andrade 2018).

In 2021, UK personal trainer Tom Mansfield accidentally measured out way too much pre-workout caffeine powder, drinking the equivalent of almost 200 cups of coffee. He died within an hour.

A legal inquest into Tom’s death found a staggering blood caffeine level of 392 mg/L in his system. To place that figure in perspective, 250 mg and 500 mg doses of caffeine given to healthy adults produced peak blood caffeine levels of 7 mg/L and 17 mg/L, respectively.

In the early hours of New Year’s Day 2018, 21-year-old Australian Lachlan Foote made a protein shake, adding pure caffeine powder to the mix. The amount he added is unknown, but in a 2:07 am Facebook message to friends, Lachlan complained his protein powder tasted "kinda bitter" and wrote: "I think my protein powder has gone off."

Lachlan then lost consciousness in the bathroom of his family home. His family found him “dead and cold on the bathroom floor" later that morning. The coroner’s report listed “caffeine toxicity” as the cause of death.

Caffeine anhydrous powder is a white substance that can easily be mistaken for numerous other supplements or kitchen ingredients. I submit it is wholly unsuitable for general use as a supplement when it must be measured out in minute amounts and where miscalculation can (and does) result in painful death.

So please stay the heck away from powdered caffeine. Your life is worth far more than the price margin between powdered and encapsulated caffeine. Pay the extra for tablets or real coffee, and live to train another day.

Speaking of real coffee, whether it offers the same ergogenic benefit as isolated caffeine has long been a point of contention. So what’s the deal? Is there any ergogenic difference between a strong cup of jitter juice and caffeine tablets?

The content below was originally paywalled.

Coffee versus Caffeine

Along with caffeine, coffee contains a multitude of other components, including chlorogenic acids, ferulic acid and caffeic acid. So whether coffee offers the same ergogenic benefits as isolated caffeine is still a matter of debate.

So let’s take a look at what controlled trials show. As you read through the studies, keep in mind the ‘consensus’ sweet spot for caffeinated performance enhancement is 3-6 milligrams of caffeine per kilogram of body weight. If you weigh 75 kg, that would equate to a pre-exercise caffeine dose of 225-450 mg.

Wiles et al 1992 examined the effect of coffee on 1500 meter treadmill running. On separate occasions, eighteen male athletes were given 3 grams of instant coffee (containing approximately 150-200 mg caffeine) or 3 grams of instant decaf 60 minutes prior to the running trials. The brand of coffee is not mentioned in the paper.

The results showed ingestion of caffeinated coffee decreased the time taken to run 1500 m, increased the speed of the 'finishing burst', and increased VO2 during the high-intensity 1500 m run.

The average mean time to complete the run was 4.2 seconds faster following the ingestion of caffeinated coffee, with 14 of the 18 subjects experiencing faster times after the ingestion of caffeinated coffee.

In a closely-matched field, that margin could literally mean the difference between first and last place.

McLellan and Bell 2004 examined thirteen physically active subjects who consumed Royal Blend® coffee, Royal Blend® decaf coffee and caffeine on separate occasions 60 minutes prior, in double-blind fashion. Times to exhaustion on a cycle ergometer (stationary bike) were significantly greater for all trials with caffeine - whether it came from coffee or caffeine capsule - versus the decaf+placebo condition.

Hodgson et al 2013 examined the effects of caffeine dissolved in water, Nescafe Original instant coffee, Nescafe Original Decaffeinated instant coffee, or placebo in eight trained male cyclists/triathletes. The dissolved caffeine and instant coffee beverages provided 5 mg/kg of caffeine.

The beverages were consumed 60 minutes prior to a test involving 30 minutes of steady state cycling, followed by an energy-matched time trial of approximately 45 minutes.

During the caffeine and instant coffee conditions, the athletes reached their target energy expenditure around 5% quicker (38.35 and 38.27 minutes, respectively) than in the decaf and placebo conditions (40.23 and 40.06 minutes, respectively).

Mean power output during the time trial was significantly greater with both caffeine and coffee compared to decaf and placebo. However, no significant differences were seen in average heart rate during the TT between the various beverages.

Richardson and Clarke 2016 compared the effects of caffeine anhydrous, coffee, or decaffeinated coffee+anhydrous caffeine taken prior to resistance exercise

After a familiarization session, nine resistance-trained men completed a squat and bench press exercise protocol at 60% 1RM until failure on 5 occasions. All subjects were required to have been including bench press and squat pattern exercises in their training for at least 1 year before the study and also performing resistance training 3–4 times a week.

Before each test session, the subjects consumed either a caffeine anhydrous supplement (MyProtein, UK), Nescafé Original coffee, Nescafé decaffeinated coffee, Nescafé decaffeinated coffee+caffeine anhydrous, or placebo. Apart from the placebo and decaffeinated only conditions, all beverages were measured out to contain 5 mg/kg caffeine.

The beverages were provided 60 minutes prior to the testing sessions, with subjects given 15 minutes to consume them.

The number of repetitions performed for the squat in each of the conditions was as follows:

Nescafé decaffeinated coffee+caffeine anhydrous: 18

Nescafé Original coffee: 17

Caffeine anhydrous supplement: 15

Nescafé decaffeinated coffee: 14

Placebo: 13

As a result of the greater repetitions achieved, subjects lifted a significantly greater total weight (load x repetitions) after ingesting the regular coffee and decaf + caffeine anhydrous beverages.

There were no significant differences between conditions in the number of repetitions performed or the total weight lifted in the bench press protocol.

When the total amount lifted from both exercises was combined, 5 of 9 subjects lifted their greatest total weight during the decaf+caffeine anhydrous condition, while the remaining 4 lifted their greatest total weight during the regular coffee condition.

Trexler et al 2017 involved fifty-four young adult males who had been resistance training for at least three months prior to the study.

The study was comprised of a baseline test and a subsequent caffeine-coffee-placebo test. The baseline testing included 1RM, and repetitions to fatigue for leg press and bench press using 80% of 1RM. Ten minutes after the strength testing, the subjects also performed a repeated sprint protocol involving five maximal 10 s sprints, with 60 s passive recovery between sprints.

Forty-eight hours later, the participants returned to do it all over again. This time, in double-blind fashion, they were randomly assigned to one of 3 groups.

Thirty minutes prior to testing, one group consumed 300 mg of caffeine anhydrous, another ingested 8.9 g of Nescafé House Blend (supplying 303 mg caffeine), while the remaining group consumed a placebo.

The study had a number of limitations. Unlike all the other studies discussed here, this was a parallel arm study where the subjects were split into three groups. It was not a crossover trial where each subject received all treatments and therefore acted as their own control. The advantage of the crossover design is that it eliminates the confounding effect that may arise from baseline differences between groups. You have exactly the same metabolism, biochemistry and genes as you; the next guy or girl doesn’t.

Also, everyone in the study received the 300 mg doses of caffeine, irrespective of body weight. Given the weight of the subjects ranged from 60 to 100 kg, this meant they were individually receiving anywhere from 3-5 mg/kg of caffeine.

Furthermore, there was no familiarization session. Even in studies involving highly trained athletes, good research practice dictates the performance of a “familiarization” test prior to the study, to ensure any subsequent changes are a result of the intervention/s and not simply due to a learning effect.

Just because someone has been going to the gym for 3 or more months does not mean they are regularly performing the barbell bench press or leg press, nor that they are performing them correctly or in the manner desired by the researchers. If you’ve spent any amount of time in commercial gyms, you’ll know poor lifting technique is commonplace.

This would help explain why the placebo group increased their leg press 1RM by 13.5 kg in only 48 hours. The coffee group increased their LP 1RM by 14.6 kg, while the caffeine group increased theirs by only 7 kg, which makes no sense.

The researchers admitted that “[d]espite the recruitment of resistance-trained participants, it appeared that a learning effect or a placebo effect was observed for strength outcomes”.

The placebo group increased their bench press 1RM by 1.9 kg, compared to 1.2 and 1.7 kg in the coffee and caffeine groups, respectively.

All three groups increased the number of reps they could perform with 80% RM on the leg press and bench, but there were no differences between groups in the magnitude of treatment.

In the subsequent sprint test, caffeine and coffee seemed to increase total work output (calculated from the distance per revolution multiplied by the force with the result recorded in calories or, in this case, joules) on sprint 1. The difference for caffeine was statistically significant. Throughout the remaining sprints, both caffeine and coffee attenuated the decline in total work output seen with placebo.

The results weren’t earth-shattering, but seemed to find a benefit for caffeine and coffee during the sprint protocol. It’s hard to know what to make of the strength findings due to the study’s obvious flaws.

Clarke et al 2018 compared Nescafé Original coffee (providing approximately 3 mg/kg caffeine), Nescafé Original Decaffeinated coffee and placebo when taken 60 minutes prior to a competitive one-mile run. The study involved thirteen trained male runners and was conducted in a double-blind, randomized, crossover fashion.

Race time was significantly faster after caffeinated coffee (mean time 04:35:37) compared with decaf (04:39:14) and placebo (04:41:00).

Karayigit et al 2022 examined the effects of low (3 mg/kg) and moderate (6 mg/kg) caffeine doses from coffee on repeated sprint performance in females. In a randomized, double-blind, crossover design, 13 female team-sport athletes completed a familiarization test and three sprint trials, each 4 days apart.

The sprint protocol consisted of 12 × 4-second sprints on a cycle ergometer interspersed with 20 s of active recovery.

Sixty minutes prior to the sprint tests, participants consumed 3 Nescafe Gold instant coffees, with caffeinated and decaffeinated versions used and dissolved in 500 ml of hot water. The regular Nescafe Gold contained 36 mg of caffeine per 1 g of coffee; this was mixed with decaffeinated version to achieve the lower 3mg/kg dose.

Both doses similarly improved the average peak power output attained by participants during the repeated sprint test compared to placebo.

Niknam 2024 compared the effects of low-dose espresso coffee, high-dose espresso, decaffeinated espresso, and no beverage upon repeated sprint performance in randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled, and double-blinded fashion.

The high-dose espresso consisted of 18 g of caffeinated ground coffee (Lavazza Espresso Italiano, double shot), supplying 160 mg of caffeine.

The low-dose espresso was a combination of 9 g of the caffeinated ground product and 9 g of decaffeinated ground coffee (Lavazza Espresso Decaffeinato, double shot), supplying 80 mg caffeine.

The placebo was made from 18 g of the Lavazza decaf, and supplied 10 mg of caffeine.

The subjects were twenty-four male basketball players who performed a familiarization session, then the 4 separate test sessions a week apart from each other.

Sixty minutes before the test session, participants drank the coffee or placebo. The test involved a warm-up, followed by ten 30-m sprints performed every 30 seconds on a basketball court.

Total sprint time, mean sprint time and best sprint time were all significantly reduced after ingestion of the high-dose espresso compared with the other three conditions. Low-dose espresso resulted in better times than no beverage, but showed no statistically significant advantage compared to the placebo decaf drink.

The Nay Studies

Not all intervention trials have found a performance benefit for coffee. Let’s look at these non-supportive studies, and see if we can make some sense of the findings.

Graham et al 1998 compared the effects of coffee, decaf and caffeine in a double-blind fashion in nine young adults who were active endurance runners. Drip-filtered ground coffee was used for the coffee treatment, but the brand or source is not mentioned.

In all the coffee and caffeine trials, the caffeine dose was 4.45 mg/kg body weight (i.e. 334 mg for a 75 kg person). One hour after consuming caffeine/coffee/placebo, the subjects jumped on a treadmill and ran at 85% VO2max until voluntary exhaustion.

Plasma concentrations of caffeine and paraxanthine (the major metabolite of caffeine) were similar in all three caffeine trials 60 minutes prior to, at the start of, and at the completion of exercise.

Despite this, only ingestion of the caffeine capsules resulted in a significant increase in time-to-exhaustion (7.5-10 minutes compared with with the other four trials).

There was no difference in time-to-exhaustion between the placebo, decaf, decaf+caffeine capsule, and regular coffee trials.

Lamina and Musa 2009 compared 5, 10 and 15 mg/kg caffeine doses and placebo in 20 untrained Nigerian male students performing 20-meter shuttle run tests. This test involves running back and forth continuously between two lines 20 m apart in time to recorded beeps. If the line is not reached before the beep sounds, the subject is given a warning and must continue to run to the line, then turn and try to catch up with the pace within two more ‘beeps’. After a second warning, the subject is eliminated from the test.

The coffee source was Capra Nescafe (Capra Nestle Company Abidjan, Cote De Voire). The subjects consumed each beverage 60 minutes prior to the test in 200 ml of water. With a mean body weight just shy of 59 kg, the pre-run caffeine doses averaged 300 mg, 600 mg and 900 mg, respectively.

Despite these hefty doses, the researchers observed no difference among treatments in the number of exercise laps or run time.

A couple of things immediately stand out about this paper. The subjects were described as non-athletes, which means they’d probably never performed the 20-m shuttle run test before. Yet there is no mention of a familiarization session, which likely means it never happened.

Also, the subjects were described as “aged between 18-23 years” and “non regular users of caffeine”. If that was the case, the hefty 600 and especially 900 mg doses would likely have had these lads bouncing off the walls. Such large caffeine doses would almost certainly have induced an array of side effects, such as jitteriness, anxiety, nervousness, irritability, perspiration, palpitations, nausea and gastrointestinal upset. Yet the paper contained no mention of side effects. The researchers didn’t even report the effect of these large caffeine doses on blood pressure or heart rate.

This raises a number of possibilities: Side effects occurred but the researchers failed to report them, the subjects were genetic freaks immune to the effects of caffeine, or the treatments didn’t contain the amounts of caffeine they were supposed to.

It’s hard to know what to make of this paper, given the curious anomalies. What I will say without hesitation is you should avoid using very high caffeine doses, such as 10 and 15 mg/kg. They are not required for a performance-enhancing benefit, and will probably make your day memorable for all the wrong reasons.

Clarke et al 2016 involved twelve recreationally-active males who completed sprint tests on a cycle ergometer on four separate occasions in a double-blind, randomized, crossover fashion. The tests involved a 2-minute warm-up, followed by eighteen maximum-effort sprints lasting 4-seconds, with 116 seconds of recovery between sprints.

Forty-five minutes before each test, the participants ingested either a caffeine anhydrous supplement (MyProtein, UK), Nescafé Original, a taste-matched placebo beverage, or no beverage. The supplement and Nescafé beverages provided 3 mg/kg of caffeine.

Neither coffee nor caffeine produced any increases in peak power output or mean power output compared to the placebo or no-beverage conditions.

Marques et al 2018 examined the effect of Nescafé instant coffee and decaf on the 800 m run times of 12 amateur endurance runners.

After a familiarization session, two 800 m trials were performed one week apart on a 400-m athletic track. In double-blind, crossover fashion, the subjects consumed the beverages after overnight fasting. Before one trial, they consumed the decaffeinated coffee, before the other they consumed enough regular coffee to deliver 5.5 mg/kg caffeine.

Despite this sizable caffeine dose, the 800 m run times were near identical between the regular coffee and decaf treatments (2:39 versus 2:38 min:sec, respectively).

To Recap

The above discussion includes eight studies in which regular (naturally caffeinated) coffee produced some measurable degree of performance enhancement. In some cases the reported benefit was equal to or superior to that of isolated caffeine.

The above discussion also includes four studies that found no benefit from coffee ingestion. In one of these studies (Graham et al 1998), caffeine but not coffee prolonged running to exhaustion time. The brand of coffee was not mentioned. One possible explanation is that coffee beans from different regions and producers may vary widely in their content of non-caffeine components, and that the coffee used in the Graham study may have featured an unusually large amount of substance/s with the potential to impair the actions of caffeine. But without a chemical analysis of the coffee that was used, we’ll never know.

Lamina and Musa 2009 used large amounts of coffee ostensibly providing very high doses of caffeine but found no improvement when untrained subjects performed 20-meter shuttle run tests. There were numerous anomalies with this study, and it was the only one I could find that examined the effect of caffeine on the 20 m shuttle run test. This precludes me from placing any weight on it.

Clarke et al 2016 found no improvement in repeated performance of 4-second sprints after coffee ingestion, but isolated caffeine also failed to produce any improvement. The data on caffeine and repeated sprint performance are mixed. As discussed above, Karayigit et al 2022 observed an increase in average peak power output during a series of 4 s sprints after low and moderate caffeine ingestion via Nescafé Gold. Schneiker et al 2006 found isolated caffeine increased mean peak power and total amount of work performed during 18 x 4-s sprints with 2-min active recovery. However, other studies have found no effect of isolated caffeine on performance of repeated 4-10 s sprints (Glaister 2012; Bernardo 2024).

Marques et al 2018 found no benefit of coffee on 800 m run times when compared to decaf. No caffeine anhydrous comparator was used, so we don’t know whether isolated caffeine would have produced any improvement in this sample.

In Summary

We have one study where an unknown brand of coffee failed to replicate the performance enhancement seen with isolated caffeine. Otherwise, commonly available coffee brands (Nescafé and Royal Blend instant, Lavazza ground) have replicated the performance-enhancing effects of isolated caffeine under controlled circumstances.

If you choose to go the instant coffee route, Nescafé Original and Gold contain 34 and 36 mg of caffeine per 1 g of coffee powder, respectively. The generic USDA database listing for regular, ground coffee cites 31.4 mg of caffeine per 1 g of powder.

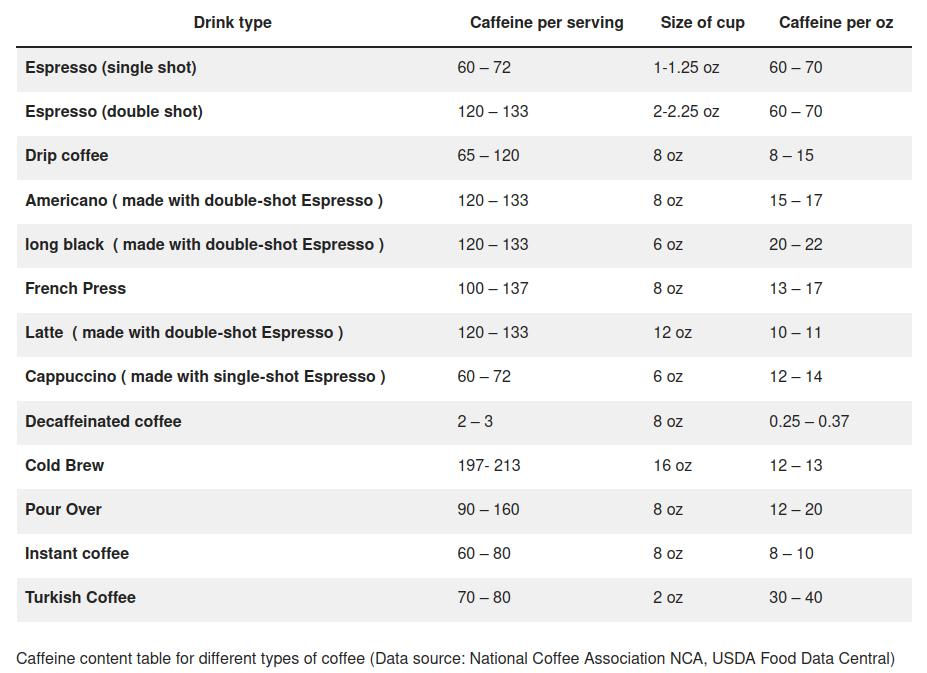

If you have Mediterranean sensibilities and would rather pluck hairs from a sleeping grizzly than drink instant coffee, the following table shows the caffeine content of various other types of coffee beverages.

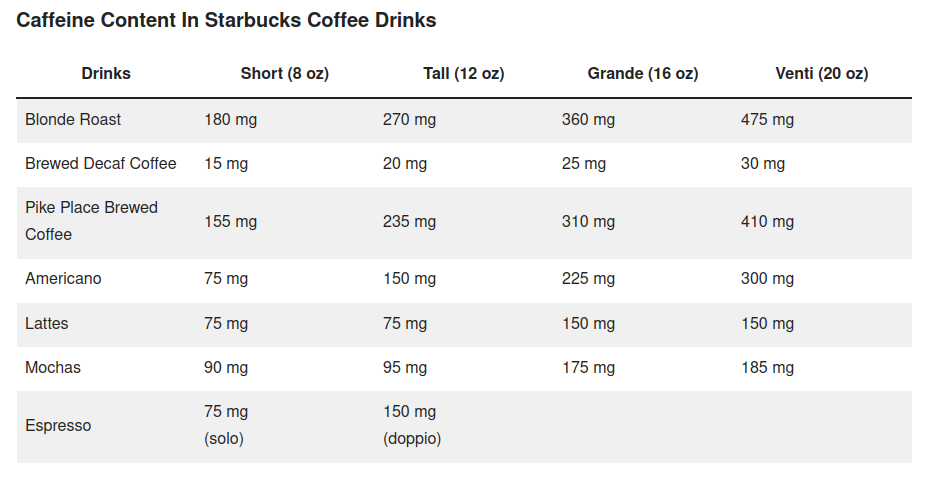

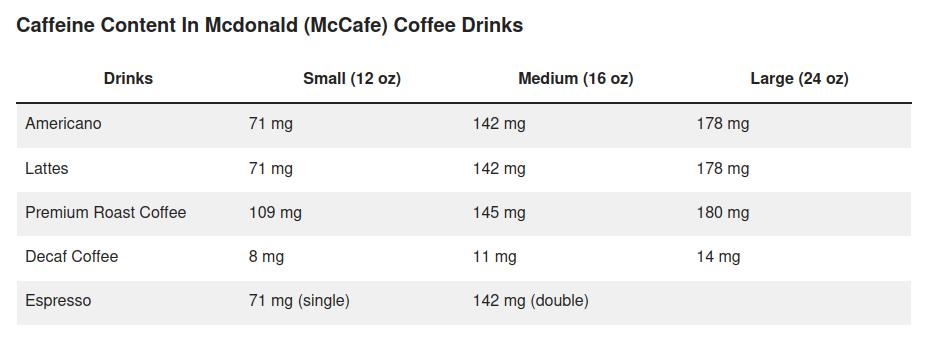

And for those of you who get your coffee fix from Starbucks (not popular in Australia, because Italians got here before the coffee multinationals) or MacDonalds:

Leave a Reply