We all know that different bodyparts require their own exercises in the gym. If you want stronger pecs, you don't add another ab exercise to your routine. If you want to broaden your delts, you don't start doing more hamstring exercises.

Duh.

But what about doing different exercises for the same bodypart or, more to the point of this article, doing the same exercises but altering the positioning of your hands or feet in order to hit certain areas of a muscle or muscle group?

Can you really make a certain section of muscle grow or, in compound movements involving multiple muscle groups, transfer the primary growth stimulus onto a different muscle?

The content below was originally paywalled.

Those of you who've been hitting the weights for any length of time will know bench presses with a medium to wide grip are done primarily for pecs, but if you want to place the emphasis on the triceps, you are told to use a narrow grip.

Wide-grip pulldowns, we're told, work the upper lats, while close-grip pulldowns with a supinated (palms up) grip place more emphasis on the lower lats.

Up until now, the only scientific attempt to validate these theories was via the performance of EMG studies. Trainees were hooked up to EMG machines while they performed different variations of an exercise, and researchers observed which parts of the muscle 'lit up' the most. Areas of muscle showing the most electromyographic activity were assumed to be the areas being stimulated the most during a particular exercise variation.

There are two problems with this type of research.

The first is that these studies have been known to return conflicting results.

Let's use the example of the gastocnemius, one of the two main calf muscles. The gastrocnemius is the muscle that, when developed, takes on a diamond- or kite-shaped appearance and visually dominates the upper half of your lower leg.

Leimann et al EMG-tested the time-honoured gym maxim that calf raises with toes pointing inwards and heels angled outwards 'work' the outer gastrocnemius muscle, while performing the same exercise with your toes angled outwards and heels inwards 'works' the inner gastrocnemius.

And that's what they found. Calf-raises with toes angled in lit up the outer calf to a greater extent than with toes angled outwards, and vice versa.

A 2017 paper by Marcoir et al reported similar findings.

A paper published that same year by Pereira et al, however, found no difference in EMG activation between the three foot positions.

The second problem with these EMG studies is that they are short-term studies, in which subjects are monitored during single workouts. No attempt is made to divide subjects into random groups and have them actually perform the different variations on a long-term basis to see if any actual differences in muscle growth occur.

As a result, exercise prescription for muscle groups has largely been a matter of gym folklore, muscle mag articles and empirical observation.

The lack of scientific clarity has led to different approaches to the idea of exercise variation. At one end of the spectrum is the keep-it-simple viewpoint. In response to the idea that you can alter a muscle's shape by using different variations of an exercise, proponents of this view often respond with "ah, that's all bullsh*t!" and an all-knowing dismissive wave of their hand. "Just get in the bloody gym and lift the bloody weight!"

Followed by a slurp of beer, a loud macho sigh that indicates the satisfying of a hard-earned thirst, then an attempt to crush the beer can against their head.

At the other end of the extreme are those who get so caught up in the idea of working a muscle thoroughly from every possible angle that their routine eventually becomes bogged down with a myriad of esoteric exercises, some performed in rather curious and eyebrow-raising positions. The sheer volume of their exercise selection necessitates intricate split routines and lots of time spent in the gym. Often, their physical development does not reflect the inordinate amount of time these convoluted routines demand. That’s because they’ve lost sight of the fundamental requirement for muscle and strength gains, which is brief, intense but consistent effort on the basic movements.

In between these two extremes is your average trainee, who performs one to three exercises per bodypart. In bodybuilding circles, it is routine practice to perform multiple exercises for the same muscle group in order to achieve more complete development (an example would be the use of barbell rows, lat pulldowns and pullovers for the upper back muscles).

Finally, an RCT on the Subject

Thankfully, we now have the results of a study in which researchers actually bothered to examine this issue over the longer term.

A group of sports scientists from Brazil decided to test the belief that altering foot position on calf exercises could in fact affect which part of the calf experienced the most growth.

For nine weeks, they had young men train 3 times per week on a whole body routine. Twenty-nine men began the study, but it seems 7 were dumped for being slackers who failed to complete at least 80% of the training sessions.

The twenty-two remaining averaged 23 years and 78.1 kg in weight. The subjects were required not to have been resistance training over the 4 months before the start of the study, but to have had a training experience of at least 6 months. It seems the researchers wanted subjects familiar with weight training procedures, but stipulated a 4-month buffer period so that previous training didn't effect the results.

The supervised resistance-training program was performed three times per week (Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays) in the afternoon over the 9 weeks. (e.g., bench press, lat pulldown, triceps pushdown, biceps curl, leg press, and leg curl) in addition to the calf-raise exercise.

The calf-raise exercises were performed unilaterally (one leg at a time) in a pin-loaded seated horizontal leg-press machine. The reason for unilateral performance instead of the usual bilateral variation was because each leg of each subject was randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups according to foot position for the calf-raise exercise: Feet pointing outward (FPO), feet pointing inward (FPI), and feet pointing forward (FPF).

During weeks 1-3 they performed 3 sets of 20–25 repetitions, increasing to 4 sets during weeks 4–9.

Calf-raise exercises were performed in the maximum range of motion, with the knee extended, in a tempo of 1:1:2 seconds (concentric, concentric peak, and eccentric phases, respectively), and subjects were cued to “squeeze the muscle” on each repetition, mainly during the concentric peak phase. When approaching momentary muscular failure (last 3–5 repetitions), subjects were instructed to carry out the movement at whatever velocity allowed them to execute the 1-second peak contraction phase, focusing on “squeezing” the targeted muscle portion.

For the FPO or FPI condition, subjects positioned their foot at 45° externally or internally rotated (including both ankle and femur rotation, as necessary), respectively, or when this could not be achieved, at the maximum angle according to the subject’s mobility.

For the FPF condition, the foot was positioned forward-pointing, with no lateral or medial rotation. Duct tape was used in the leg-press platform as a guide to be followed.

The training load was progressively increased each week by 5–10%, according to the number of repetitions performed during each training session to ensure the subjects kept performing their sets to (or very near to) failure in the established repetition zone.

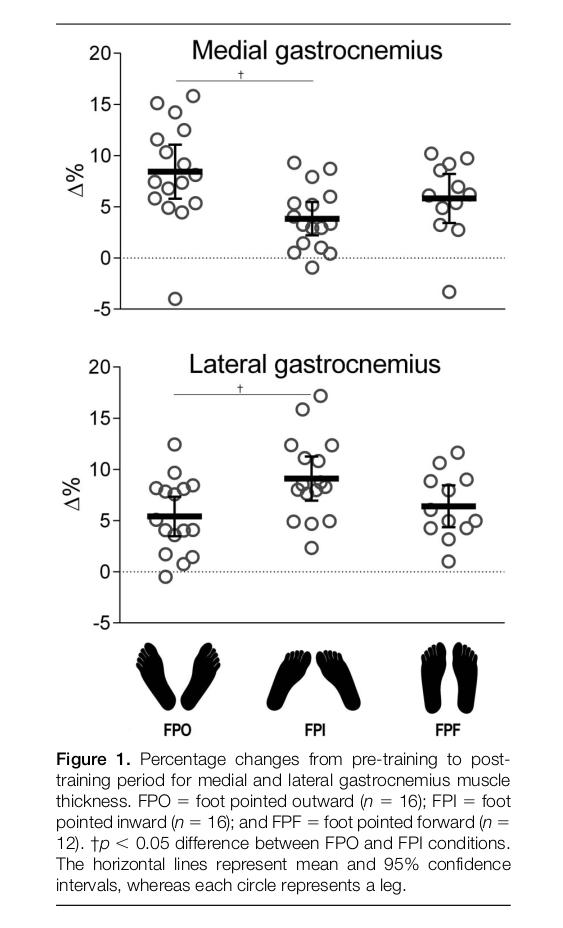

In the week immediately prior to and after the 9-week training intervention, muscle thickness of the gastrocnemius was measured at the relevant angles via ultrasound.

After the training period, there were observed increases of small-to-moderate magnitude on muscle thickness of the medial and lateral gastrocnemius for FPO, FPI, and FPF conditions. Although the calves have a reputation as difficult muscles to hypertrophy, the rate of growth was similar to what researchers have reported for other muscle groups.

A significant effect of the condition was observed for the increases in the medial (inner) gastrocnemius between FPO and FPI conditions, with a greater increase for the FPO condition.

Similarly, a significant effect of the condition was observed for the increases in the lateral (outer) gastrocnemius, with a significant difference favoring the FPO condition.

The feet forward position, not surprisingly, produced more balanced increases in muscle thickness, making it the best choice for beginners and those whose calf development is already well-balanced.

For those whose calf development is 'imbalanced', with either outer or inner heads of the gastrocnemius out of visual proportion to the other, this study indicates you are not at the mercy of genetics, but can in fact even things out by altering the way you perform your calf exercises.

It also shows that the ability to manipulate your training results by varying your foot or hand position is more than just gum folklore, but a scientific reality.

Leave a Reply