Sorting through the research to get you the best results and save you money.

In this article:

How do you determine the right CoQ10 dose?

Are expensive ‘high-absorption’ supplements worth the extra cost?

Are the lavish claims made for ubiquinol true?

The content below was originally paywalled.

If you’ve ever shopped for CoQ10 on a website like iHerb or Vitacost and felt overwhelmed by the myriad of dosages, formulations and marketing claims, you’re not alone.

Before we sort through the maze of options and marketing hyperbole to find the most cost-effective forms of CoQ10, a little biochemistry is in order.

CoQ10 occurs in the human body in two bioactive states, ubiquinone (CoQ10) and ubiquinol (CoQH2). Until the late 2000s, CoQ10 supplements were sold in the form of ubiquinone, sometimes referred to as ubidecarenone. In 2007, Japanese manufacturer Kaneka patented a process for manufacturing ubiquinol, which is now widely available to the public.

Ubiquinone is referred to as the “oxidized” form of CoQ10 and ubiquinol is the “reduced” form. They’re the same molecule save for the addition of two electrons when CoQ10 is reduced, which turns it into ubiquinol.

Ubiquinol supplements are heavily promoted as being superior to their ubiquinone counterparts. Some of the more absurd claims getting around include assertions that, before your body can utilize CoQ10, it must first be converted to the ubiquinol form.

The reality is that, inside our bodies, ubiquinone and ubiquinol are converted into each other then back again in a continuous cycle.

Your body needs both forms. Ubiquinone is essential for cellular ATP energy production as it shuttles electrons along the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Ubiquinol, meanwhile, is an important lipid-soluble antioxidant that prevents peroxidation (free radical damage) of cellular membranes.

CoQ10 Absorption and Blood Levels

Before we discuss the veracity of the claims made for ubiquinol and other “high-absorption” CoQ10 supplements, it behooves me to clarify just what researchers and supplement companies mean when they refer to the “absorption” and “bioavailability” of CoQ10.

In studies comparing different CoQ10 formulations, bioavailability and absorption are typically determined by measuring the post-consumption rise in blood levels of CoQ10.

If supplemented CoQ10 fails to cross the intestinal wall in sufficient amounts and produces little to no rise in blood CoQ10 levels, then our cells won’t have access to extra CoQ10.

Typically, when making supplement dosage recommendations, the standard practice is to talk in terms of how many milligrams or grams of a nutrient one should take daily.

That’s not the correct approach with CoQ10 supplementation. As you’re about to learn, CoQ10 levels vary widely from person to person, as does the individual response to supplements. Some people need far higher dosages to bring their blood CoQ10 levels up to a certain level than other folks do.

What is an Optimal CoQ10 Blood Level?

In a world where research expenditure is heavily geared towards pharmaceutical drugs and politically-correct causes such as meat-, fat- and cholesterol-bashing, we still don’t know a whole lot about optimal CoQ10 levels in healthy humans.

If you have your blood CoQ10 levels checked, the result will most likely be expressed in terms of µmol/L or µg/ml (the latter is sometimes expressed as mg/L).

The research indicates the overwhelming majority of non-supplemented individuals will display fasting blood levels of CoQ10 below 2.0 µmol/L (1.72 mcg/ml). Males tend to have higher blood levels than females, and older folks tend to display higher levels than younger people.

From a sample of 705 Finnish adults, Kaikkonen et al 2002 reported plasma CoQ10 values ranging from 0.40 to 1.72 µmol/L for males and 0.43 to 1.47 µmol/l for females.

Among a Cincinnati sample of 148 black and white adults, Miles et al 2003 reported plasma CoQ10 values ranging from 0.53 to 2.07 µmol/L for males and 0.50 to 1.84 µmol/l for females.

While organ levels of CoQ10 decline with age, numerous research groups have found higher blood levels among older folks. In a sample of sixty-six healthy, statin-free subjects from Seville, Spain, with an age range of 19–85 years, Pozo-Cruz et al 2014 reported mean plasma CoQ10 levels of 0.94 µmol/L for young folks (mean age 20.3 years) and 1.19 µmol/L for older subjects (mean 65.4 years).

Tekle et al 2010 compared blood CoQ10 status among 400 similarly-aged females from Poland, Serbia and Sweden. Half of the Serbian population was from Belgrade. The other half were from areas near petroleum refinery complexes, fertilizer plants, and oil depots in locations heavily bombed during the war of 1999. The damage to these facilities resulted in pollution of soil and water by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, ethylene dichloride, vinyl chloride and metallic mercury. These compounds appeared in water, locally grown food and also in fish from the Danube. Dietary questionnaires revealed the Serbian women consumed far higher meat and fish intakes than the Polish or Swedish cohorts.

The women from all three countries were healthy and reported not taking vitamin E or CoQ10 during the previous six months.

The mean plasma CoQ10 levels of the Polish and Swedish women were 0.82 and 0.98 µmol/L, respectively. Among the Serbian women from Belgrade, mean plasma CoQ10 was an impressive 1.98 µmol/L, with a range of 1.5 to 3.5 µmol/L.

However, among the Serbian women from the war-affected and heavily-polluted areas, the mean CoQ10 level was a disturbingly low 0.16 µmol/L; none of these women showed plasma CoQ10 values above 0.5 µmol/L. Plasma levels of vitamin E were also the lowest among this Serbian cohort, suggesting their defenses against toxic free radical activity were being overwhelmed.

When More Really is Better

There are several lines of evidence indicating it is advantageous to have higher blood levels of CoQ10.

Vanderbilt University researchers identified a significant inverse association between plasma CoQ10 levels and lung cancer risk in current smokers, but not in former/never smokers.

When Italian researchers compared melanoma patients with healthy controls, they found serum CoQ10 level was significantly higher among the latter (mean 0.497 versus 1.27 µg/ml, respectively). Among the patients, those with serum CoQ10 less than 0.6 µg/ml were 8 times more likely to develop metastases during the 3-year study.

In a 2012 paper, researchers from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center compared the CoQ10 levels of 23 cardiac arrest subjects with those of 16 healthy controls. Median CoQ10 level in the patients was significantly lower than in controls (0.28 µgmol/L versus 0.75 µgmol/L, respectively). Furthermore, the median CoQ10 level in patients who died was significantly lower than in those who survived (0.27 vs 0.47 µgmol L, respectively).

In Part 1, I discussed the three largest RCTs examining the effect of CoQ10 and mortality outcomes. Two of those trials reported baseline and post-supplementation blood CoQ10 levels.

In the Q-Symbio Trial, 420 heart failure patients were randomly assigned to 300 mg CoQ10 daily or placebo. At 106 weeks, far fewer heart failure deaths had occurred in the CoQ10 group. Sudden cardiac and stroke deaths were also lower in the CoQ10 group.

Baseline serum CoQ10 levels in Q-Symbio were 0.91 and 1.14 µg/ml among placebo and treatment patients, respectively. At week 16, serum CoQ10 levels remained unchanged in the control group but had risen to 3.01 µg/ml in the supplemented group. At 106 weeks, serum CoQ10 averaged 2.01 µg/ml in the supplemented group.

The KISEL-10 Trial involved elderly males and females averaging 78 years of age. The combination of 200 mg/day of coenzyme Q10 capsules and 200 μg/day of selenium significantly lowered cardiovascular mortality at 5.2 years of follow-up.

At 48 months, mean serum levels of CoQ10 levels in the supplemented group rose from 0.82 µg/L at baseline to 2.19 µg/L.

So in the Q-Symbio and KISEL-10 trials, long term supplementation resulting in mean serum CoQ10 levels of 2.01 and 2.19 µg/ml (2.33 and 2.54 µmol) was associated with favorable morbidity and mortality outcomes.

However, the mean level is not necessarily the optimal level. Not everyone in the treatment groups experienced superior outcomes. It would be instructive to know the relationship between the magnitude of increase in blood CoQ10 levels and favorable outcomes within the treatment groups of those trials. But alas, neither the Q-Symbio nor KISEL-10 papers provide any such information.

Langsjoen and Langsjoen 2008

This paper by Texas cardiologists Peter and Alena Langsjoen did explore the issue of optimal blood CoQ10 levels, albeit in a specific group: Heart failure patients.

The Langsjoens reported that, during the course of a six year study of supplemental CoQ10 in 126 heart failure patients, only those with plasma CoQ10 levels >2.5 µg/ml (2.9 µmol/L) showed significant clinical and echocardiographic improvement.

Due to individual variation in patients’ absorption of CoQ10, they commenced a flexible dosing schedule whereby CoQ10 dosage was increased as necessary to attain a plasma CoQ10 level of > 2.5 µg/ml.

In their 2008 paper, they reported on seven end-stage heart failure patients who were rapidly worsening in spite of “maximal” medical therapy. All seven patients were already receiving ubiquinone, at a mean daily dose of 450 mg/day (range 150 mg to 600 mg/day).

Despite this, the mean plasma CoQ10 level was only 1.6 µg/ml, with a range of 0.9 µg/ml to 2.0 µg/ml.

All seven patients were changed from ubiquinone to ubiquinol (supplied by Kaneka) in the hope of improving their rapidly deteriorating condition.

After switching from supplemental ubiquinone to ubiquinol, an increase in plasma CoQ10 levels was observed in all seven patients. The mean plasma CoQ10 level achieved was 6.5 µg/ml, a 303% increase over the baseline levels seen with ubiquinone supplementation.

The levels achieved ranged from 2.6 µg/ml at 3 months to 9.3 µg/ml at 20 months (3.01-10.78 µmol).

Improvements in clinical status were seen in all patients, and echocardiographic measurements improved dramatically in four of the seven.

Unfortunately, one patient stayed on ubiquinol for only three months. Although improving in heart function, she stopped all CoQ10 due to mental deterioration from cerebrovascular disease and passed away three months later.

The prognosis for patients with end-stage heart failure is very poor, with mortality as high as 94% at 12 months. The Langsjoens reported that, at the time of authoring their 2008 paper, six of the seven patients survived longer than expected and remained stable between NYHA class I-III on ubiquinol, for an average of 12 months (range 9 to 20 months).

The Langsjoens reported that all seven patients had right and left heart failure with pulmonary edema, ascites and leg edema. “It is our assumption that intractable intestinal wall edema in these critically ill patients is impairing CoQ10 absorption. We consider this a vicious cycle wherein worsening CHF leads to worsening edema with decreased CoQ10 absorption, decreased CoQ10 plasma CoQ10 levels and further worsening of CHF resulting in death. Up until the current experience with ubiquinol we have never been able to alter this inexorable cycle which can occur in patients previously stable for many years.”

Target Blood Level Recommendations?

To recap: Mean serum CoQ10 levels of 2.01 (2.33 µmol/L) and 2.19 µg/ml (2.54 µmol/L) were associated with favorable morbidity and mortality outcomes in Q-Symbio and KISEL-10, while the small Langsjoen case study series with end-stage heart failure patients found clinical benefit with a mean plasma CoQ10 level of 6.5 µg/ml (7.54 µmol/L).

No-one knows the optimal target blood level of CoQ10 for currently healthy people who wish to optimize their health and longevity.

Most of the trials above, and the Langsjoen case reports, involved heart failure patients.

KISEL-10 study was the only of those studies not involving a cohort suffering a specific health condition, and hence the closest to a primary prevention study. However, even that study involved elderly subjects, most of whom had preexisting health conditions.

So we’re still nowhere near establishing a target CoQ10 level in healthy folks free of chronic, degenerative health conditions.

Generally speaking, when taking supplemental vitamins or hormones, the widely-held ideal is to restore levels of the relevant nutrient/hormone to the upper levels of the reference range. Accepted reference ranges are usually derived from a supposedly ‘normal’ sample of people, with outliers exhibiting unusually low or high levels excluded from the sample.

The assumption behind the reference range approach is that shooting for the higher level of the ‘normal’ range is unlikely to be harmful because, hey, it is a naturally occurring level seen in healthy humans. This is a great approach when supplementing with things like DHEA or testosterone, not so great when it comes to something like iron, where considerable evidence shows that, by the time you’re at the upper end of the normal range, your body is already struggling with an excessive and harmful iron burden.

We’ve already seen that, while most people exhibit blood CoQ10 levels under 2.0 µmol/L, levels as high as 3.5 µmol/L have been observed in healthy, non-supplementing, premenopausal women.

Given the lack of toxicity observed with both high intakes and high blood levels of CoQ10, and going by the results of the aforementioned RCTs, it seems prudent to shoot for blood CoQ10 levels that exceed the ranges seen in most populations.

In heart failure patients, judging by the Langsjoen case studies, it appears to be a case of the higher the better.

CoQ10 researcher William Judy writes:

“The Cleveland Clinic indicates that the population reference values for plasma or serum CoQ10 concentrations range from 0.36 to 1.59 micrograms per milliliter (mcg/mL). Unsupplemented normal healthy individuals who are not elderly should have a plasma CoQ10 concentration of approximately 0.8 mcg/mL. The current consensus among CoQ10 researchers is that a plasma CoQ10 concentration of at least 2.5 mcg/mL is required for significant benefit of CoQ10 in the adjuvant treatment of patients with heart failure. In patients with neurodegenerative diseases, plasma CoQ10 concentrations >3.5 mcg/mL are required for therapeutic effect.”

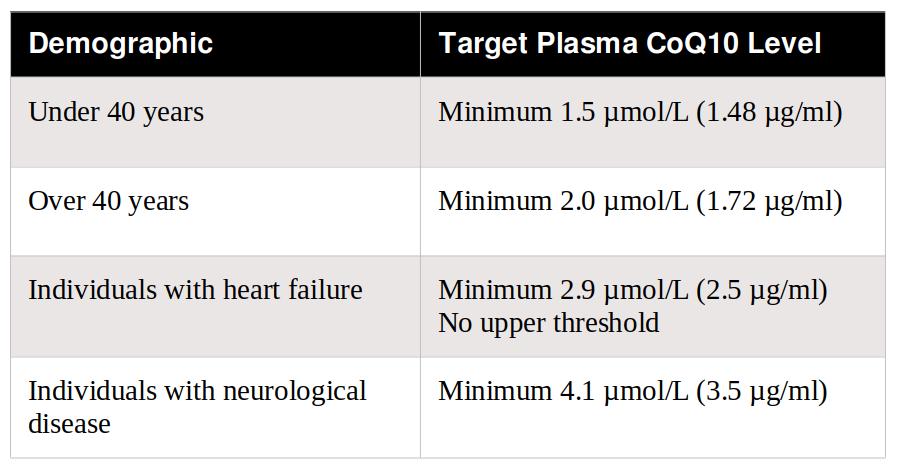

So based on the admittedly sparse data to date, here are my tentative minimum plasma CoQ10 targets:

The under and over 40 recommendations assume a currently healthy, disease-free state of health. If you have a family history of, say, heart disease or cancer, you might want to shoot for even higher levels.

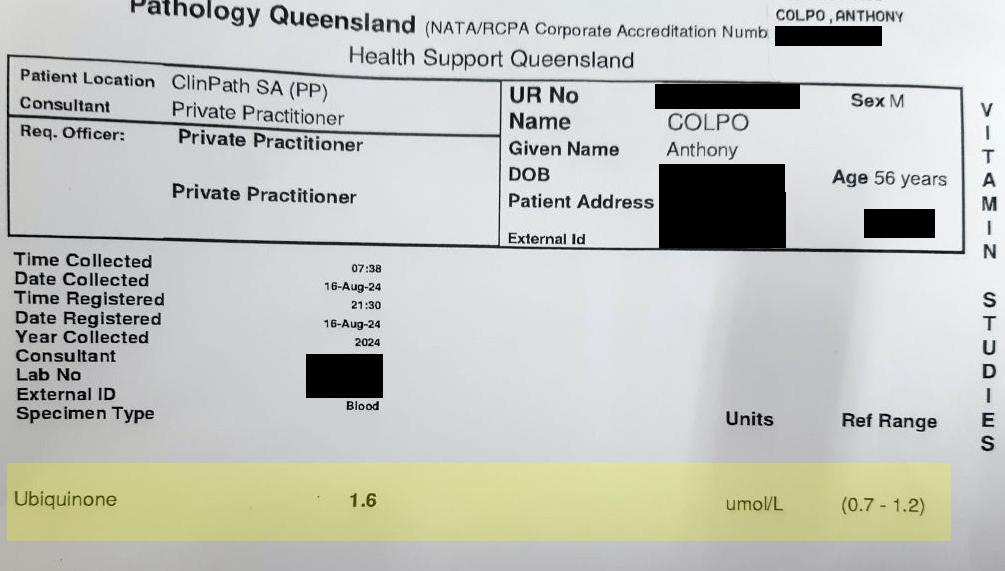

After writing Part 1 of this series, I decided to have my own fasting plasma CoQ10 level tested. This was the result:

My fasting plasma CoQ10 level was 1.6 µmol/L. The reference range cited on the RHS side of the lab printout was 0.7-1.2 µmol/L, presumably a representative range obtained from a sample of Australian adults.

When my blood was drawn for this test, I’d been taking a CoQ10 supplement I’d purchased in late April from Shopee, a popular Thai online shopping website. The brand is Daitea, and each softgel capsule contains 200 mg of ubiquinone suspended in soybean oil. The product is advertised as made in the USA and was available on Shopee, if I recall, for around AU $15, which is damn cheap for 120 x 200 mg CoQ10 capsules. Prior to purchasing the Daitea product, I’d been using a Doctors Best “High Absorption” product containing BioPerine, always at a dose of 100 mg daily. Because each capsule of the Daitea product contained twice that amount, I consumed one capsule every second day.

After four months of what I now know to be a sub-optimal dosage schedule of the Daitea product, my plasma CoQ10 level is 1.6 µmol/L, way above the apparent Australian reference range upper threshold of 1.2 µmol/L. A doctor or lab consultant who hasn’t researched CoQ10 in any depth would look at that result and conclude I’m doing great.

As of this writing, I’m 56 years old, still fit enough to haul my butt to the top of Spain’s Sierra Nevada via the masochistic Angliru-like approach through Monachil, and free of any degenerative health conditions.

And I’d very much like to stay that way. But with a family history of cardiovascular disease, I’m not being complacent.

I intend to elevate my CoQ10 levels even higher, beyond the minimum 2.5 µmol/L in the table above. If, like me, you’re already taking a CoQ10 supplement and want to raise your blood CoQ10 levels even higher, there are a few possible strategies:

Take a higher dosage;

Take 2-3 divided dosages daily, instead of a single daily dose;

Take a CoQ10 product shown to possess superior bioavailability.

All things being equal, option #3 would seem the logical starting point. However, supplements touted as having superior absorption typically come with a hefty price premium. Paying ten times more for a CoQ10 supplement that has been shown in controlled studies to offer, on average, a three- or four-fold greater rise in blood ubiquinone levels doesn’t make much financial sense. As you’re about to learn, that’s the kind of proposition presented by some of the most highly-touted CoQ10 supplements.

Comparing Different Forms of CoQ10

Manufacturers have created numerous formulations in an attempt to improve the bioavailability of CoQ10 supplements. Some of these include:

SoluQ10, SterolQ10, Q-Gel: These are “solubilized” ubiquinone formulations containing, among other things, polysorbate 80. Solublization is great, polysorbate 80 isn’t. The latter is a synthetic emulsifying agent used in supplements, foods and cosmetics to blend things that would not normally mix together, like water and oil. Polysorbate 80 is also found in drugs and many vaccines, and has been named along with carboxymethylcellulose as impacting “intestinal microbiota in a manner that promotes gut inflammation and associated disease states.”

As a result, I do not recommend any CoQ10 formulation containing polysorbate 80. If you wish to avoid this ingredient, be sure to check the labels. Avoid any product bearing the Q-Gel, SoluQ10, or SterolQ10 monikers.

As with most ‘high-absorption’ products, the research reporting superior absorption for CoQ10 products containing polysorbate 80 in human subjects was conducted/sponsored by the manufacturers. In contrast, a single-dose study by Danish researchers found no statistically significant difference in CoQ10 absorption between two polysorbate 80-containing formulations and a hard gelatine capsule ubiquinone product, all containing 100 mg of CoQ each.

MicroActive Co-Q10, Q10Vital: These formulations pair ubiquinone with β-cyclodextrin. Cyclodextrins have been widely used in the pharmaceutical industry to improve the dissolution rate and bioavailability of molecules with poor water solubility. Like most CoQ10 products touted as high-absorption, these products tend to be quite expensive.

A single-dose, crossover study by Slovenian researchers compared the bioavailabity of the following CoQ10 products in 21 healthy older adults aged 65–74:

NuU Nutrition CoQ10 100 mg, a “standard” ubiquinone supplement comprised of powder-filled capsules containing 100 mg of CoQ10.;

NOW® Ubiquinol, containing 100 mg of Kaneka ubiquinol per capsule;

Valens Quvital® syrup containing the company’s Q10Vital® water-soluble form of ubiquinone. The syrup contains 100 mg of ubiquinone per 5 mL. Along with ubiquinone, Q10Vital® contains β-cyclodextrin.

The study was partly funded by Valens Inc., the manufacturer of Quvital.

After correcting for differences in baseline CoQ10 levels, Quvital resulted in 2.4-fold higher plasma levels of CoQ10 than the standard ubiquinone product, while ubiquinol produced a 1.7-fold increase that did not reach statistical significance.

Formulations containing piperine and BioPerine®: Piperine is a naturally-occurring substance, credited for the pungency of black pepper and long pepper. Piperine is reputed to have liver-protective, anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties, but that’s not why it is used in some CoQ10 formulas. Piperine has demonstrated the ability to improve the absorption of various supplements and drugs.

BioPerine® is a patented extract produced by Sabinsa Corporation and licensed to other supplement companies to use, standardized to contain a minimum of 95% piperine. It has been endowed with GRAS (generally recognized as safe) status.

I’ve been able to find only one study examining the effects of adding piperine or BioPerine®. It was conducted by Sabinsa researchers and involved healthy adult male volunteers with pre-supplementation fasting CoQ10 values between 0.30 and 0.60 mcg/ml.

Daily consumption of soft-gels supplying 90 mg ubiquine daily, plus 5 mg piperine as BioPerine®, produced slightly but non-significantly higher blood levels of CoQ10 than ubiquinone alone.

When a higher daily dosage of 120 mg of ubiquinone was ingested over a longer 21-day period, the addition of 5 mg piperine was accompanied by a statistically significant, 32% greater rise in plasma CoQ10. Co-administration of 5 mg piperine with 120 mg ubiquinone daily resulted in a 1.12 µg/ml increase in plasma CoQ10 levels, compared with an 0.85 µg/ml increase in the control group.

Ubiquinol: This is currently the most highly-hyped form of CoQ10 supplementation. However, chronic ingestion studies comparing the plasma CoQ10 levels achieved with of ubiquinol and other supplements are rather sparse.

Langsjoen and Langsjoen 2014 compared serum levels of ubiquinone versus ubiquinol in healthy volunteers aged 29 to 50 years. They were instructed to consume 200 mg of the CoQ10 supplements with evening meals. The subjects took Kaneka ubiquinone soft gels for four weeks, followed by a four-week washout period during which plasma CoQ10 returned to normal. They then took Kaneka ubiquinol soft gels for another four weeks.

Among the twelve subjects that completed the study, the baseline mean plasma CoQ10 level was 0.88 µg/ml (1.014 µmol/L). After 4 weeks of ubiquinone supplementation, mean plasma CoQ10 levels rose to 2.50 µg/ml. After 4 weeks of ubiquinol, they rose to 4.34 µg/ml.

Zhang et al 2018 similarly compared 200 mg per day of Kaneka ubiquinone and ubiquinol. Their study employed two-week intervention periods with a two-week washout.

The ten men who completed the study averaged 63.9 years of age. Mean levels of plasma ubiquinone rose from 0.22 to 0.60 µmol/ml with ubiquinol, compared to only 0.30 µmol/ml with ubiquinone.

Bio-Quinone, aka Myoquinone, Bioquinin: Produced by Danish company Pharma Nord, Bio-Quinone belongs to the “crystal-free” class of CoQ10 supplements. Bio-Quinone is a soft gel containing ubiquinone and soybean oil, yet shows greater absorption than other products where ubiquinone is also suspended in soy bean oil.

According to Pharma Nord, its ubiquinone is subjected to a patented heating and cooling process in which the CoQ10 crystals dissolve entirely into single molecules at normal body temperature. This matters because CoQ10 crystals in their standard form are large, possess a high molecular weight, have a melting point 10°C higher than human body temperature, and hence are poorly absorbed.

Bio-Quinone is also the CoQ10 supplement used in the successful Q-Symbio and KISEL-10 trials.

In an oft-quoted 2019 paper, Spanish researchers (Lopez-Lluch et al) reported a single-dose comparison of seven different supplement formulations each containing 100 mg of CoQ10. The subjects were fourteen healthy individuals aged 18-33 years.

All seven formulations were produced by Pharma Nord, who also funded the study. Two were formulations commercially sold by Pharma Nord. One was Bio-Quinone, referred to in this study as Myoquinon. The other was Pharma Nord’s Ubiquinol QH, which is delivered in a softgel capsule containing MCT oil and vitamin C.

The other five products were produced by Pharma Nord specifically for this experiment and included five softgel products using standard softgel filling technology and a hardgel containing micronized powder.

One of the softgel products contained the same ingredients as Myoquinon but without the specialized heat/cooling procedure.

Each product was administered as a single dose in double-blind crossover fashion with a minimum of 4 weeks wash-out between intakes.

The capsules were consumed at the same time of day and with a standardized meal. Over 48 hours, mean CoQ10 area under the curve (AUC) levels were highest for Myoqinon (25.15 µg/ml), followed by Ubiquinol QH (14.2 µg/ml).

The peak serum concentration of CoQ10 during the 48 hours was also reported for Myoquinon, followed by Ubiquinol QH.

All the other formulas demonstrated far lower bioavailability.

Given the absorption data and its RCT track record, Bio-Quinone seems like a safe, research-backed bet.

However, there’s a problem: A 30-day supply Pharma Nord’s Bio-Quinone 100 mg currently sells at the company’s website for US $53.95, which at current exchange rates equates to AUD $83 and GBP 42.50.

In this day and age of soaring living costs, that’s going to be prohibitive for many people. Here in stupidly expensive Australia, the country with the world’s second-worst household debt-to-GDP ratio and some of the world’s most overpriced rent and real estate, an extra $83 per month is a big ask.

As I write this, US online supplement outlet Vitacost is selling its house brand ubiquinone formulas (Vitacost CoQ10 and Vitacost-Synergy ToCoQ10®) for the equivalent of around US $60 (approx AU 90) for a year’s supply (assuming a 100 mg daily dose).

iHerb, meanwhile, is selling its California Gold and Lake Avenue Nutrition house brand ubiquinone formulas for even less. Currently, 360 capsules of California Gold Nutrition CoQ10 or Lake Avenue Nutrition CoQ10 can be had for US $51 and$47, respectively.

In other words, a year’s worth of the iHerb products can be had for slightly less than a mere 1-month supply of the Pharma Nord version.

For a cost-conscious consumer to justify purchasing the Pharma Nord version, they’d need evidence that Bio-Quinone provides twelve-fold greater benefits. The research to date suggests that is unlikely.

Thankfully, Bio-Quinone is not the only crystal-free ubiquinone formula available.

Thorne also offers a non-crystalline ubiquinone supplement; iHerb is currently selling 60 x 100 mg capsules of the Thorne product for US $46 (AU $71).

A cheaper option again is the crystal-free Endurance Products CoenzymeQ10, which uses the CoQsol-CF® technology licensed from Soft Gel Technologies Inc. At US $46.99 for 120 x 100 mg capsules, you’re looking at a far cheaper crystal-free option. However, the company doesn’t ship internationally, only within the US.

Cost Effectiveness of Ubiquinol

Although the research indicates crystal-free ubiquinone formulations currently rank as the best absorbed, ubiquinol currently enjoys the most press as a “superior” form of CoQ10.

The cheapest price I could find on iHerb for 100 mg capsules was US $50 (around AU $78) for a 120 day supply of the Qunol brand, which uses Kaneka ubiquinol. On an annual basis, that’s 3 times the cost of the iHerb house brand products.

As discussed above, ubiquinol produces 1.7 and 2 times greater mean CoQ10 plasma levels than regular (not crystal-free) ubiquinone products in adult subjects.

Along with cost, there’s something else to be aware of regarding ubiquinol supplements. During storage, they may destabilize, so that by the time you ingest the capsules, much of the ubiquinol has in fact converted to ubiquinone. A quick way to test a ubiquinol product is to squeeze out the contents of a capsule. If the contents are yellow or orange, the ubiquinol has already oxidized to ubiquinone. If the contents are a milky white, then the CoQ10 is still in its reduced ubiquinol form.

Even if the contents of your ubiquinol supplement remain stable in storage, experiments by William Judy indicate that after ingesting a typical ubiquinol supplement, the user should expect as much as three-quarters or more of the ubiquinol to be oxidized to ubiquinone in the stomach and duodenum.

Earlier I mentioned the Zhang et al study that compared 200 mg of of ubiquinol and ubiquinone. In that study, plasma ubiquinone rose from 0.22 to 0.60 μmol/ml with ubiquinol supplementation, compared to only 0.30 μmol/ml with a standard ubiquinone formulation. However, supplemental ubiquinol only resulted in a mean 40.6% greater increase in plasma ubiquinol concentrations, a difference that was not statistically significant.

All this would suggest it is the manner in which ubiquinol supplements are processed, and not ubiquinol per se, that is responsible for the higher blood ubiquinone levels seen in some studies.

Distilling everything we’ve learned so far, crystal-free formulations are looking like the best of the numerous high-absorption options.

Increasing and Dividing the Dosage

Even if you can get your hands on a reasonably-priced crystal-free option, there’s a chance you’ll need to consume more than 100 mg a day - especially if you’re starting with a very low blood CoQ10 level.

Obviously, the cost will increase step-wise with every increase in dosage. All of a sudden, what initially looked like an affordable crystal-free option may in fact be prohibitively expensive.

For those whose only realistic option is to take a cheaper, non-cutting edge ubiquinone supplement from a reputable manufacturer, there are still ways to max out its effectiveness.

Take Your CoQ10 With Meals

The first rule of CoQ10 supplementation is to always consume your capsules with meals, no matter what formulation you are using. While some supplements are best taken on an empty stomach, most are far more efficiently absorbed when consumed with a meal, and CoQ10 is no exception. Also, as a fat soluble compound, CoQ10 should be taken with fat-containing meals.

Consuming supplements with meals may also reduce any risk of gastrointestinal upset.

Higher CoQ10 Dosages Result in Higher Blood Levels

Czech researchers evaluated serum CoQ10 concentrations in healthy male volunteers supplemented with 30 mg or 100 mg Q10 of Bio-Quinone, or placebo, as a single daily dose for two months in a double-blind RCT.

The median baseline serum CoQ10 concentration in the men was 1.26 µg/ml. The median changes in serum CoQ10 in men supplemented with 30 mg or 100 mg CoQ10 were 0.55 and 1.36 µg/ml, respectively.

Changes in serum CoQ10 concentration among individuals in the 30 mg group ranged from −0.48 to 1.68 µg/ml, with an increase occurring in 25 of 28 men. Changes in the 100 mg group ranged from −0.57 to 4.61 µg/ml, with an increase occurring in 32 of 36 men. In the supplemented men, changes in serum CoQ10 were not dependent on baseline serum CoQ10 concentration, nor age or body weight.

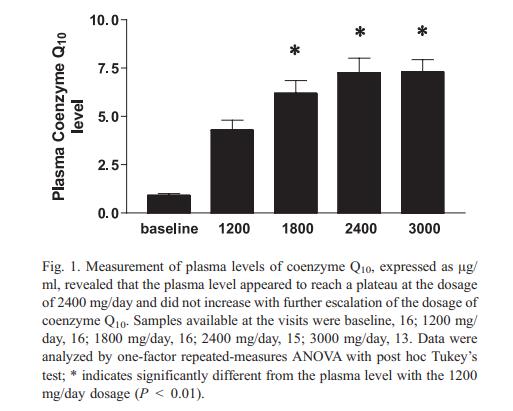

Shults et al 2004 compared plasma CoQ10 concentrations in Parkinson’s patients after high dosages of 1200, 1800, 2400, and 3000 mg/day of chewable ubiquinone. CoQ10 concentrations appeared to plateau at the 2400 mg/day dosage, where the mean plasma concentration was 7.4 µg/ml (8.6 µmol/L).

Divided Dosages Produce Higher Blood CoQ10 Concentrations

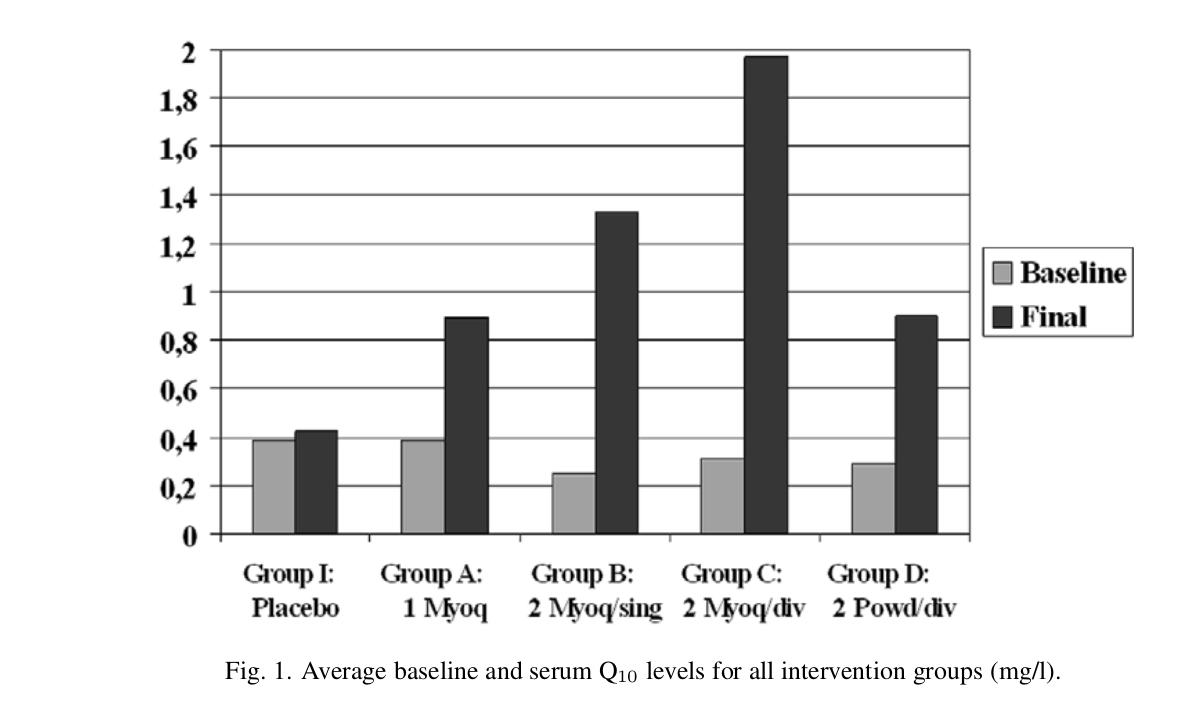

In a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial involving sixty healthy Indian men aged 18–55 years, Singh et al 2005 compared various dosages and dose strategies of Bio-Quinone 100 mg or crystalline 100 mg CoQ10 powder capsules. The subjects were divided into five groups based on the following supplementation modes:

1 x 100 mg capsule of Bio-Quinone at dinner (100 mg CoQ daily);

2 x 100 mg capsules of Bio-Quinone taken together at dinner (200 mg CoQ daily);

2 x 100 mg capsules of Bio-Quinone in a divided dose, one at breakfast and one at dinner (200 mg CoQ10 daily);

2 x 100 mg capsules of crystalline uniquinone powder daily, one at breakfast and one at dinner (200 mg CoQ10 daily);

1 x placebo (soybean oil) capsule at dinner.

All subjects were advised to take the capsules with meals, for twenty days. The results are shown in the graph below.

As you can see, the baseline mean serum CoQ10 levels of the men were very low, something the researchers suspected was due to the vegetarian diet predominating in India.

As expected, a daily Bio-Quinone dose of 200 mg resulted in higher serum CoQ10 levels at day 20 than a 100 mg dose. However, dividing the daily 200 mg dose into two separate intakes, one at breakfast and another at dinner, produced a significantly higher serum CoQ10 level than a single daily dose of 200 mg at breakfast.

Of interest to those on a budget, a similarly divided 200 mg dose of a low-tech crystalline CoQ10 formulation produced a sightly greater rise in serum CoQ10 than a single 100 mg dose of Bio-Quinone. Again, if you’re watching your pennies, you have to seriously question the wisdom of spending twelve times as much for your CoQ10 when simply doubling the dose of a less expensive formula could deliver the same result.

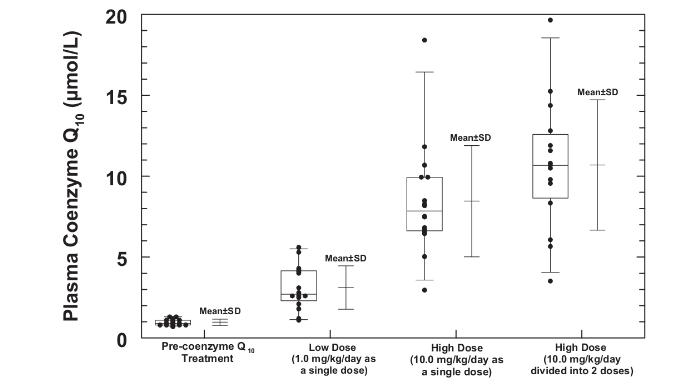

Miles et al 2006 compared the effects of single versus divided CoQ10 dosages in children with Downs Syndrome. A liquid ubiquinol formulation was consumed during 3 consecutive four-week phases. During the first four weeks, the children consumed the CoQ10 at a single dose of 1 mg/kg/day in the evening.

During the following four-week phase the dosage was increased to 10 mg/kg/day, again taken in the evening.

During the final four weeks, the dosage was kept at 10 mg/kg/day, but divided into two equal morning and evening servings. The results are shown below.

In Summary

If you suffer a health condition such as fatigue, it may be possible to try various CoQ10 products and dosages and notice tangible improvements without having your blood concentrations tested.

Several years back, an Argentinian chap in his thirties who’d recently migrated with his young family to Australia complained to me of muscle soreness and fatigue. His doctor back in Argentina had decided it would be a great idea to place this young, fit, healthy individual with no cardiovascular issues on statins. He stopped taking the statins because of the side effects, but the muscle soreness and weakness remained.

I explained to him that statin drugs were notorious for depleting CoQ10, and that this was the likely cause of his problems. A few days later, I gave him a half-full bottle of Vitacost CoQ10 capsules. If I recall correctly, they were 100 mg capsules, and I told him to do a “loading dose” for a week or two at 300 mg before continuing at 100 mg daily.

A week or so after that, he was profusely thanking me for the capsules, because he had already noticed a dramatic improvement in his energy levels. For the first time in years, he felt like he did before he took the toxic statins.

For the rest of us taking CoQ10 for preventive purposes, or are taking it for therapeutic purposes but yet to notice improvement, it is important to have our blood CoQ10 concentrations monitored. To do otherwise, to proceed in the absence of any objective marker, is flying blind.

If money is no object, then I’d recommend one of the crystal-free ubiquinone formulas.

If money is an issue, then I’d recommend a regular ubiquinone product from a reputable manufacturer, employing divided doses if necessary to maximize blood concentrations.

Either way, I’d recommend monitoring the efficacy of whatever product and dosing strategy you employ with regular blood testing.

CoQ10 is a very safe supplement. In the final installment, I’ll discuss the safety and toxicity research and any possible interactions with medications.

Please note: I do not and have not received any royalties, remuneration or freebies from manufacturers or suppliers of any products mentioned in this article.

Leave a Reply