The latest single-set training research, and what it shows about training to failure.

Debate still rages as to whether single-set or multiple-set training is better. However, one thing is certain: In terms of results achieved for time invested, single-set training is a clear winner. When you can achieve similar results in a fraction of the time, the choice is a no-brainer for busy people or those with multiple training commitments.

Prominent practitioners of single-set training, such as the late Arthur Jones and Mike Mentzer, adamantly insisted your single work set of an exercise should be taken to the point of momentary muscular failure. This is the point where you cannot move the weight further in good form, no matter how hard you try.

Stopping short of failure, according to the traditional gospel of single-set training, means you are not fully working the muscle and is akin to leaving potential size and strength gains on the table.

A recent study1 by sports scientists from Brazil, the US, UK and Australia set out to see if this is actually true.

The content below was originally paywalled.

They recruited young, resistance-trained men and women, and randomly assigned them to one of two groups:

a group that trained to failure on all exercises (FAIL);

a group that trained with two “repetitions in reserve” (2-RIR), i.e. 2 reps short of failure.

Apart from the failure and non-failure conditions, both groups underwent the same training protocol. Over an eight-week period, they performed two whole body workouts each week. At each of these training sessions, they performed a single set of nine exercises targeting all major muscle groups.

A total of 50 volunteers from a university population commenced the trial; 42 completed it (34 males, 8 females). Mean baseline characteristics were as follows: height = 172.5 cm; weight = 79.9 kg; age = 21.9 years; body fat = 21.4%; training experience = 4.4 years.

The following outcomes were measured before and after the eight-week training intervention:

Changes in muscle thickness for the biceps, triceps, and quadriceps femoris, measured by ultrasound;

1RM on the bench press and squat movements, using a Smith machine;

Lower body muscle power, assessed via the countermovement jump (CMJ);

Lower-body local muscular endurance, assessed by performing reps-to-failure on the leg extension exercise with a load equivalent to 60% of the participant’s initial body mass.

Participants were also assessed for their ability to gauge RIR, by performing one set with a load corresponding to 75% of 1RM and verbally identifying the point at which they perceived reaching a 2-RIR, before continuing the set to failure.

The participants were advised to maintain their customary nutritional habits throughout the study.

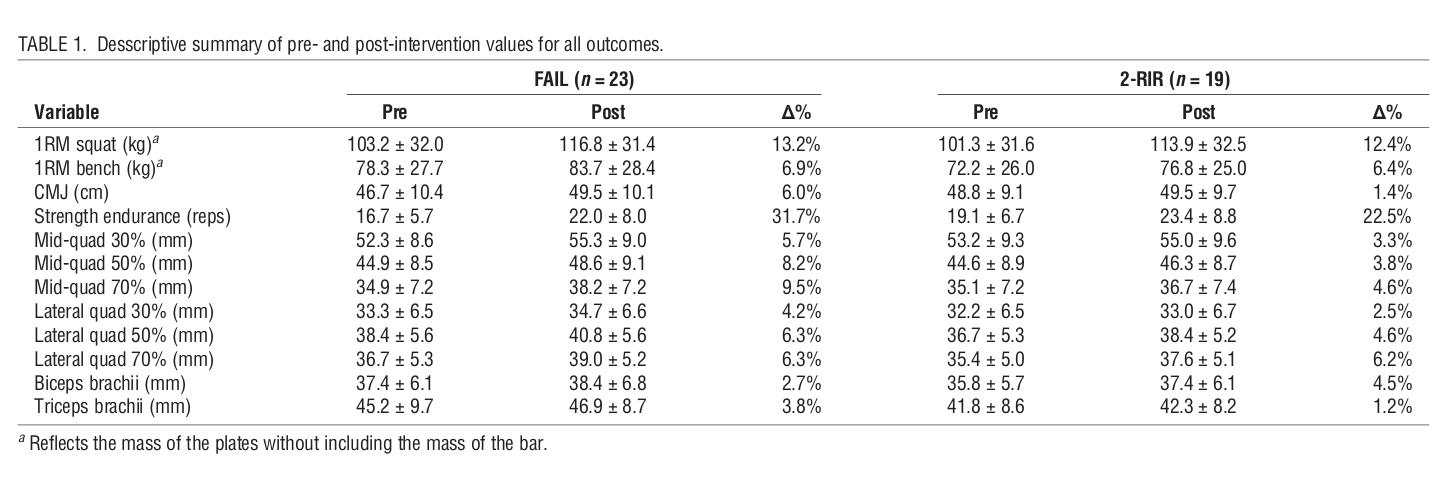

The pre- and post-results are encapsulated in the following table:

As you can see, 1RM gains for the squat and bench increased by a similar percentage in both groups.

Countermovement jump height increased to a greater degree in the FAIL group, as did reps-to-failure with a light weight on the leg extension.

As for the changes in muscle thickness, the pre- and post-intervention muscle thickness data suggests a greater hypertrophic effect from the FAIL regimen. The notable exception was biceps brachii thickness, which experienced a greater % increase in the 2-RIR group. Ultrasound measurement is not a perfectly exact science but depends on operator skill and consistency, but let’s assume the operator was well-trained and consistent. Only one site was measured on the biceps and triceps, meaning potential gains in thickness in neighboring biceps sites may have been missed. Another possibility is that, because this was a parallel group trial and not a crossover trial, the RIR-2 group may simply have experienced better biceps gains irrespective of which protocol they followed.

The overall finding of similar strength gains but a trend to greater muscle hypertrophy for the FAIL group reflects what has been reported in numerous reviews examining multiple-set studies.

These reviews have consistently found little difference in strength outcomes when failure and non-failure training are directly compared in intervention studies. Two recent reviews reported a non-significant trend in favor of non-failure training for strength gains (Vieira 2021; Robinson 2024).

Consistently training to failure on the big compound movements (squat, bench, deadlift, leg press, etc) is taxing to the nervous system, and the problem of accumulating fatigue may be exacerbated on higher-volume routines. It’s worth keeping in mind that the Hermann et al study discussed above not only featured a single-set routine, but a minimal twice-weekly workout frequency.

I hate to sound like a broken record, but this study - like so many others - did not instruct participants to consume a calorie surplus, which is crucial for muscular weight gain. Therefore, we don’t know whether the differences in muscle thickness between groups would have been magnified in the presence of a more anabolic caloric intake.

The takeaway from this study is that, during an eight-week intervention using a single-set regimen, training to failure produced similar 1RM gains and slightly greater muscle thickness changes, indicative of greater hypertrophy.

Hermann T, et al. Without Fail: Muscular Adaptations in Single-Set Resistance Training Performed to Failure or with Repetitions-in-Reserve. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc, 2025; 57 (9): 2021-2031. doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000003728

Leave a Reply