In fact, it's one of the leading causes of emergency room visits.

“Acetaminophen is one of the safest drugs around,” claims a September 25 Nature article, one of many written in the wake of the recent White House announcement linking the drug to autism1.

The Nature claim is nonsense. Far from being one of the safest drugs, acetaminophen is a leading cause of poisoning hospitalizations.

The content below was originally paywalled.

Also known as paracetamol, it is sold under numerous brand names, including Tylenol, Panadol, Excedrin, and, to the displeasure of yours truly, Calpol.

I just typed “acetaminophen toxicity” into PubMed; it returned 6,927 results.

By way of comparison, I also typed “ephedra toxicity” into the PubMed search field; it returned only 148 results.

Those of you whose squatted and benched your way through the 1990s will remember ephedra, a herb that contains ephedrine. Ephedra has a long history of use in traditional Chinese medicine, where it is known as Ma Huang. Ephedra has thermogenic and anorectic (appetite suppressant) properties, and its thermogenicity is enhanced when taken along with caffeine. Unlike most fat loss supplements, the ephedra+caffeine combo has proven itself effective in clinical trials2345.

EC is not a benign compound. Because of its stimulant properties, it is contraindicated for those with hypertension and tachycardia. Nor is it a bright idea for those taking MAO-inhibitor drugs; a study with healthy volunteers given ephedrine along with the MAO-I moclobemide produced significant blood pressure elevations and side effects in 11 of 12 volunteers, including palpitations, headache, and lightheadedness6.

But when used as directed by healthy subjects, the EC combo possessed a safety profile the current batch of toxic weight loss drugs (Mounjaro, Ozempic, Wegovy, etc) could only ever dream of. As a result, it became a very popular supplement among those seeking fat loss.

Until 2004, that is, when the pharma-friendly and supplement-hostile FDA banned its use, with media outlets claiming the supplement was “linked” to 155 deaths over the dozen or so years it was available. The following year, a Federal judge struck down the ban, but it was reinstated upon appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit in 2006.

The contrasting fates of acetaminophen and ephedra highlight just how terribly hypocritical our governments and health agencies are.

In 2003, the US National Institutes of Health commissioned a review on the efficacy and safety of ephedra and ephedrine alkaloids for weight loss or to enhance athletic performance. It admitted a meta-analysis using data from 50 trials found:

“No serious adverse events (death, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular/stroke events, seizure, or serious psychiatric events) were reported.”

“However,” objected the NIH, “because participants in clinical trials must meet eligibility criteria, including the absence of specific underlying health risks, they may not represent the general population.”

Gee, no kidding. The trials for the recent COVID pseudo-vaccines featured strict eligibility criteria which screened out frail elderly folks, people with serious chronic health conditions, and pregnant women. Yet the NIH, CDC, FDA and other government-associated pathological liars had no qualms whatsoever about aggressively recommending the poison darts to all these groups. In fact, in most countries, the elderly were first on the list to receive the highly toxic COVID ‘vaccines’.*

The hypocrisy hardly ends there.

Acetaminophen overdose continues to be a leading cause of accidental and intentional poisoning, with more than 80,000 cases reported in 2021 to US Poison Centers. In the US, acetaminophen is responsible for 56,000 emergency department visits, 2,600 hospitalizations, and 500 deaths annually.

The reason there are only 500 deaths from such a large number of serious ED admissions is that an antidote exists in the form of the amino acid N-acetylcysteine. When administered in the first eight hours after overdose, it prevents acute liver failure, the need for liver transplantation, and death.

Disgracefully, acetaminophen has been heavily promoted for pediatric use. Approximately 30,000 pediatric acetaminophen poisoning cases are reported to the National Poison Data System annually.

Acetaminophen toxicity is the most common cause of liver failure in the United States and the second most common cause of liver transplantation worldwide.

Importantly, around 50% of these poisonings are unintentional, often resulting from patients misinterpreting dosing instructions or unknowingly consuming multiple acetaminophen-containing products.

Here in Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) admits:

“Each year in Australia, around 225 people are hospitalised and 50 Australians die from paracetamol overdose, with rates of intentional overdose highest among adolescents and young adults.”

Acetaminophen, then, is a dangerous drug that routinely causes the kind of carnage ephedra never even came close to. In a 2017 interview, Aric Hausknecht, M.D., a New York neurologist and pain management specialist, said “Tylenol is by far the most dangerous drug ever made.”

In 2015, a group of German researchers wrote that acetaminophen “is probably one of the most dangerous compounds in medical use, causing hundreds of deaths in all industrialized countries due to acute liver failure.”

Yet, unlike ephedra, acetaminophen remains freely available. Heck, you can buy it at the supermarket, along with your eggs, bread and Corn Flakes.

No health agency has ever talked of banning acetaminophen, despite its obvious and well-established toxicity.

In 1977, an FDA Advisory Committee recommended all Tylenol products include a clear warning about exceeding maximum daily dosages and the risk of liver damage. The FDA ignored the committee’s warning until 1994, when Johnson & Johnson was sued by a patient who needed a liver transplant after taking Tylenol and consuming alcohol.

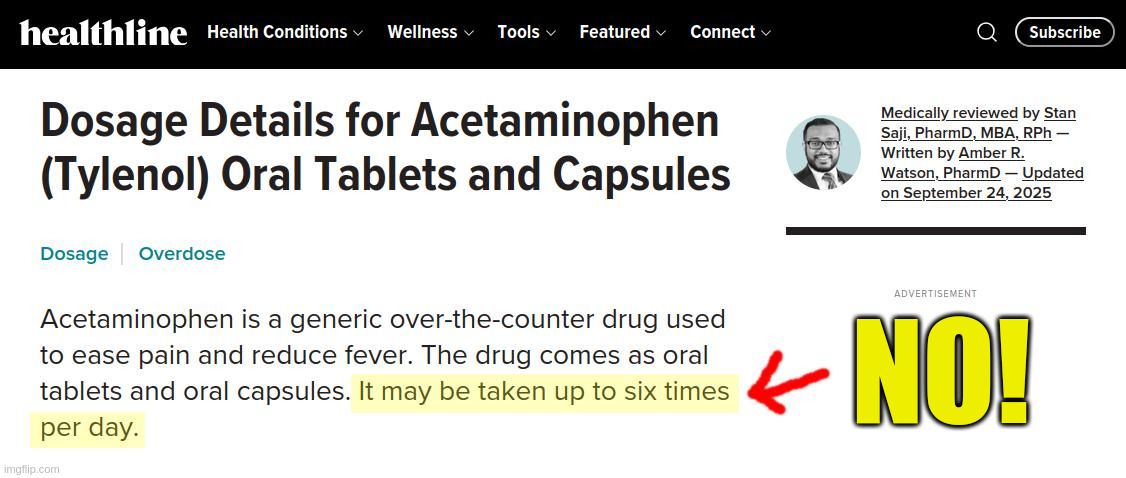

In 2011, the FDA asked drug manufacturers to limit the strength of acetaminophen to 325 mg per tablet/capsule in prescription drug products, which are predominantly combinations of acetaminophen and opioids. It also called for a “Boxed Warning” highlighting the potential for severe liver injury and a “Warning” highlighting the potential for allergic reactions. These were to be added to the package insert, which few people read. Manufacturer compliance was required by March 2014.

Over-the-counter products containing acetaminophen were not affected by this action; information about the potential for liver injury was already required on the label for these products.

In 2023, a group of researchers, some of whom had received money from a raft of drug companies including GlaxoSmithKline (manufacturers of Panadol), Gilead (manufacturers of remdesivir) and Moderna (manufacturer of myocarditis and death), praised the FDA’s mandate7.

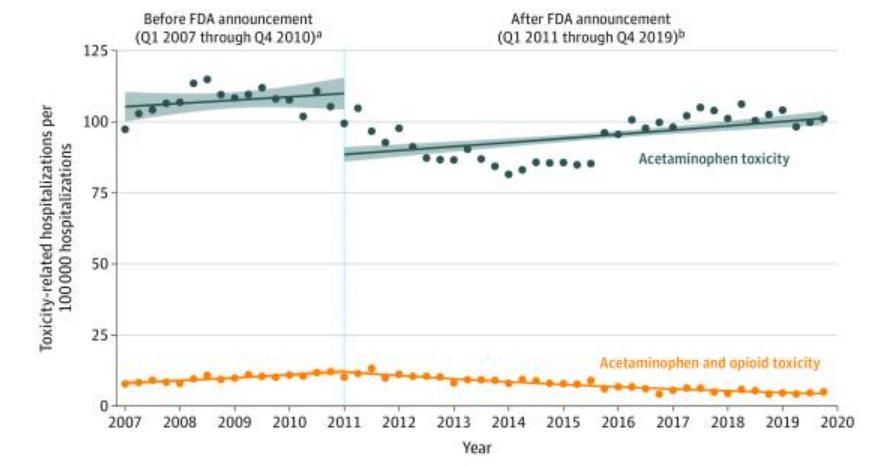

They stated in their abstract that, after the FDA mandate, “there was a significant decline in the yearly rate of hospitalizations involving acetaminophen and opioid toxicity and a significant decrease in the proportion per year of hospitalizations due to ALF with acetaminophen and opioid toxicity.”

Sounds great, but what they dubiously omitted from the abstract was the subsequent rate for acetaminophen-only hospitalizations, which constitute the overwhelming majority of acetaminophen admissions. That inconvenient matter was delayed until six pages deep into the paper, at which point we learn that acetaminophen-only hospitalizations increased from 2014.

As Figure 1 from the paper shows, the gradual decline in acetaminophen+opioid hospitalizations was overshadowed by the increase in acetaminophen-only hospitalizations.

It’s worth noting the data from this analysis only extends through Q4 2019, and fails to capture acetaminophen’s trajectory through the COVID scam. As the fear porn reached fever pitch in March 2020, dolt-like members of our patently stupid drugs-are-the-answer-to-everything culture rushed to stock up on the toxic analgesic. Johnson & Johnson reported it was running its Tylenol manufacturing at maximum capacity in North America “to meet surging demand due to the fast-spreading coronavirus outbreak”.

As you would expect from any medication being employed against a non-existent virus, acetaminophen did diddly squat to treat the artist formerly known as Cold’n’Flu8.

Straya Mate

In response to the 50 Aussie deaths a year from acetaminophen, the hopelessly corrupt TGA announced in February that the maximum size of paracetamol packs available for sale in stores would be reduced from 20 tablets/capsules to 16. In pharmacies without the supervision of a pharmacist, the pill count would be reduced from 100 to 50 tablets or capsules. The TGA had originally proposed a reduction to 32 pills, but the industry-funded agency eventually settled on a 50-count.

Woohoo.

So you can still walk into a pharmacy and grab 50 acetaminophen tablets, which would likely kill you if you took them all at once (do not try this at home; if you are experiencing suicidal thoughts, please reach out to someone, anyone, until you find a sympathetic ear). You can then walk across to Woolworths and buy another 16 capsules. You can then walk down the mall to Coles and buy another 16.

You can then return the very next day and do it all over again. All within the same shopping center.

The commonly recommended daily cut-off dosage for acetaminophen toxicity is 4,000 mg. That constitutes only 8 of the 500 mg and 12.3 of the 325 mg pills. These are easily attained doses by people who have been led to believe acetaminophen is a largely harmless drug that is safe to consume multiple times daily.

According to the Merck Manual, acute acetaminophen toxicity typically results with ingestion within 24 hours of a total dose ≥ 150 mg/kg. For a 70 kg adult, that equates to 10.5 grams.

Acetaminophen Versus Your Liver

Liver metabolism of acetaminophen generates a toxic, highly reactive intermediate known as N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI).

At non-toxic doses, acetaminophen produces minimal amounts of NAPQI, which conjugates with hepatic glutathione (your body’s most abundant antioxidant) to produce non-toxic cysteine and mercaptate compounds that are excreted in the urine.

However, in cases of acetaminophen toxicity, an increased production of NAPQI occurs and depletes liver glutathione stores.

Complications of acetaminophen poisoning extend beyond liver failure and may include kidney failure, encephalopathy, and death.

In 2022, a group of authors audaciously published a review titled “Why paracetamol (acetaminophen) is a suitable first choice for treating mild to moderate acute pain in adults with liver, kidney or cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disorders, asthma, or who are older”.

But they would say that. The review was funded by GlaxoSmithKline which, as noted above, manufactures and markets acetaminophen. Two of the authors were employees of GlaxoSmithKline, while the other two had received honorarium payments for serving as members of the “GlaxoSmithKline Global Pain Faculty.”

Who Needs This Poison, Anyway?

The irony of all this is that acetaminophen is largely being used by people who don’t really need it. People with serious, chronic pain can be forgiven for resorting to drugs in an attempt to find relief, but with annual global sales of $10 billion, it’s obvious this demographic comprises a small portion of acetaminophen users.

According to Medline and the FDA, acetaminophen is used “to relieve mild to moderate pain from headaches, muscle aches, menstrual periods, colds and sore throats, toothaches, backaches, reactions to vaccinations (shots), and to reduce fever.” (Bold emphasis added)

Excuse me while I face palm.

Excepting period pain and vaccine reactions, I’ve experienced all the above in years gone by, and not once did I use acetaminophen.

Why not?

Because:

I have an “only when absolutely necessary” policy towards drug use, and;

I’m a grown-ass man.

The only time I used this junk was circa mid-1990s, when I underwent an inguinal hernia (aka “sportsman’s hernia”) repair. A friend who’d already had the same surgery went on and on about how much pain I’d be in after the operation.

Then after the procedure, the nurse who discharged me also banged on about the severe pain I was likely to experience, and gave me a pack of Panadeine Forte (which combines paracetamol and codeine). She warned that as the anesthetic wore off that night, the pain would start kicking in and I should take 2 tablets. I was supposed to repeat this dosing every two hours or so.

“Wow, sounds like I’m in for some nasty-ass pain!”, I thought to myself.

So I went home. Several hours later, as I was sitting talking to visiting friends, I started to feel it in the area where I’d been cut. So I reluctantly did as instructed and took 2 Panadeine Forte. I did not take any more that night.

The next morning, I woke and got up.

Was I in agony?

No.

In fact, I didn’t really feel any pain unless I coughed or laughed, at which point I got a very sharp reminder that I’d just been operated on in the groin area.

“Is this it?” I asked, shaking my head in bemusement.

I didn’t need drugs; I just needed to avoid coughing and laughing.

Look, I get that machismo is overrated, but there are times in life when “Harden the F**k Up!” really is the best advice. In the case of acetaminophen, it is literally the kind of advice that could save lives.

The rush to stock up on acetaminophen during the out-and-out fraud known as COVID shows just how pathetic Homo lardassis has become. We’ve become so soft as a society that people will take toxic drugs to get relief from “mild to moderate pain”. Highly materialistic modern societies promote the notion that life should never be anything other than cushy and comfortable. People have become so attached to this notion that they see nothing at all unusual about taking drugs repeatedly through the day to quell any deviation from this idealistic state of pain-free being.

Mind conditioning of modern society has been so effective that it is those who shun toxic drugs who are now considered strange, irresponsible and ‘conspiracy theorists’.

Surveys regularly confirm a relatively poor ability of respondents to identify products containing acetaminophen, and many remain clueless about the drug’s potential toxicity9101112.

Even doctors and pharmacists display surprisingly high levels of ignorance about this drug. A 2007-2008 survey of Alabama physicians found only 76% were aware of the maximum daily dose of acetaminophen. Only 83% identified Lorcet and 75% Darvocet as acetaminophen-containing products. Although 72% of physicians stated they provide specific instructions to patients when prescribing acetaminophen-containing medications, the information provided was limited13.

The problem is global. A 2015 survey of pharmacists in Pakistan found only 70.6% of respondents correctly identified the maximum daily dose of acetaminophen. While 85.2% of the pharmacists correctly identified hepatotoxicity as the primary toxicity associated with acetaminophen, only 47% of pharmacists reported providing specific instructions and precautions when dispensing the drug14.

*Here in Australia, aged care residents, the elderly, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders aged 55 and over, and “Adults with an underlying medical condition, including those with a disability” were among the first to receive the cull shots.

One things these demographics have in common is a high rate of people who rely on pensions, disability allowances or some other form of government subsidy. These are people who the fiscally irresponsible government can no longer extract taxes from, and instead must provide financial support to.

Adam D. (2025). Tylenol is more than 130 years old - why is it still the gold-standard painkiller? Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-03116-2

Boozer CN, Daly PA, Homel P, Solomon JL, Blanchard D, Nasser JA, Strauss R, Meredith T. (2002). Herbal ephedra/caffeine for weight loss: a 6-month randomized safety and efficacy trial. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 26(5), 593-604. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802023.

Hackman, RM; Havel, PJ; Schwartz, HJ; Rutledge, JC; Watnik, MR; Noceti, EM, et al. (2006). Multinutrient supplement containing ephedra and caffeine causes weight loss and improves metabolic risk factors in obese women: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Obesity, 30(10), 1545-1556. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803283

Greenway FL, De Jonge L, Blanchard D, Frisard M, Smith SR. (2004). Effect of a dietary herbal supplement containing caffeine and ephedra on weight, metabolic rate, and body composition. Obesity Research, 12(7):1152-7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.144.

Coffey CS, Steiner D, Baker BA, Allison DB. (2004). A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of a product containing ephedrine, caffeine, and other ingredients from herbal sources for treatment of overweight and obesity in the absence of lifestyle treatment. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 28(11), 1411-1419. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802784.

Dingemanse, J., Guentert, T., Gieschke, R., Stabl, M. (1996). Modification of the Cardiovascular Effects of Ephedrine by the Reversible Monoamine Oxidase A-Inhibitor Moclobemide. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology, 28(6), 856-861. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199612000-00017.

Orandi BJ, McLeod MC, MacLennan PA, Lee WM, Fontana RJ, Karvellas CJ, McGuire BM, Lewis CE, Terrault NM, Locke JE; US Acute Liver Failure Study Group. (2023). Association of FDA Mandate Limiting Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) in Prescription Combination Opioid Products and Subsequent Hospitalizations and Acute Liver Failure. JAMA, 329(9), 735-744. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.1080.

Bianconi A, Zauli E, Biagiotti C, Calò GL, Cioni G, Imperiali G, Orazi V, Acuti Martellucci C, Rosso A, Fiore M. Paracetamol Use and COVID-19 Clinical Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Healthcare, 12(22), 2309. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12222309.

Boudreau DM, Wirtz H, Von Korff M, Catz SL, St John J, Stang PE. (2013). A survey of adult awareness and use of medicine containing acetaminophen. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 22(3):229-40. doi: 10.1002/pds.3335.

Herndon CM, Dankenbring DM. (2014). Patient perception and knowledge of acetaminophen in a large family medicine service. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, 28(2):109-16. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2014.908993.

Stumpf JL, Skyles AJ, Alaniz C, Erickson SR. (2007). Knowledge of appropriate acetaminophen doses and potential toxicities in an adult clinic population. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, 47(1), 35-41. doi: 10.1331/1544-3191.47.1.35.stumpf.

Saab S, Konyn PG, Viramontes MR, Jimenez MA, Grotts JF, Hamidzadah W, Dang VP, Esmailzadeh NL, Choi G, Durazo FA, El-Kabany MM, Han SB, Tong MJ. (2016). Limited Knowledge of Acetaminophen in Patients with Liver Disease. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology, 4(4), 281-287. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2016.00049.

Hornsby, L. B., Przybylowicz, J., Andrus, M., & Starr, J. (2010). Survey of Physician Knowledge and Counseling Practices Regarding Acetaminophen. Journal of Patient Safety, 6(4), 216–220. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26632787

Ali, I., Khan, A. U., Khan, J., Kaleem, W. A., Alam, F., Khan, T. M. (2016). Survey of hospital pharmacists’ knowledge regarding acetaminophen dosing, toxicity, product recognition and counselling practices. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research, 8(1), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphs.12148

Leave a Reply