What happened when a Greek powerlifting team compared single set and multiple set training?

Regular readers know I’m highly partial to single set resistance training, often referred to in the common vernacular as “one set to failure,” “heavy duty," or “high intensity training” (HIT)*.

Single set training differs to traditional multiple set training in both brevity and intensity of effort. I like it because it achieves similar results to multiple set training in far less time.

The content below was originally paywalled.

The traditional approach to resistance training is to perform 1-3 warm-up sets of an exercise, followed by 3-5 “work” sets (and sometimes more) before moving on to the next exercise. There are even programs like German Volume Training that involve performing ten sets of each exercise in a routine.

Multiple set training has long been the de facto method of weight training. It is the strategy taught to most beginners and promoted in muscle magazines and the majority of how-to books. It is also the method practiced by most high-level strength athletes.

The world of bodybuilding and strength training has long been this way, and most people don’t question it. As with most things in life, they assume things are this way because someone, somewhere, proved this was the best way to train.

As a result, there is a lot of ingrained resistance to the idea of performing a single work set. “Champions don’t train this way,” is a common objection. “If it was the best way to train,” object others, “then everyone would be doing it.”

These objections rely on the “millions of people can’t all be wrong!” line of argument, even though recent events involving a contrived pandemic and dangerous gene therapies confirm billions of people can all be very, very wrong.

It behooves me to point out that the concept of working up to a single “top” set is not entirely foreign to ‘conventional’ training routines. Bill Starr’s famous 5 x 5 routine, immortalized in his book Only The Strong Shall Survive, involved lifting progressively heavier weights over 5 sets, hitting the heaviest weight on the fifth set. Like early single set routines, Starr’s routine involved three whole body workouts each week, revolving around the bench press, power clean and squat. Unlike traditional single set training, however, the routine featured light, medium and heavy days, so that each of the three exercises was only worked ‘hard’ once per week.

In powerlifting, training of the big three lifts (bench press, squat and deadlift), often involves working up to a maximum set. One starts out with a light weight and progressively increases the load until one “maxes out” on their top set. However, the numerous ‘assistance’ exercises employed by powerlifters are typically performed in the conventional manner, for multiple sets.

So the concept of working up to a single “heavy” or “hard” set in the gym is nowhere near as novel or bizarre as some people make it out to be.

No Champions Train This Way?

Resistance training has spawned three main sports: Bodybuilding, Olympic weightlifting, and powerlifting.

Single set training is not realistically suited for the sport of Olympic weightlifting, where success hinges upon the total combined weight achieved in the clean and jerk and snatch lifts. These lifts are highly technical and require a high degree of neuromuscular coordination. In other words, optimal performance of the Olympic lifts is a high level skill. As with any skill, mastery of the Olympic lifts requires repetitive practice.

Single set training isn’t suited to Olympic lifting for the same reason angrily kicking a heavy bag one time per session won’t ever produce a Muay Thai champion:

Practice makes perfect.

Performing a couple of warm-up sets, hoisting a heavy single, then calling it a day simply won’t cut it when it comes to training snatches and cleans at a competitive level.

Research with high level junior Olympic weightlifters suggests that a moderate level of volume is optimal; enough to extensively drill the movements but not enough to overtax one’s nervous and hormonal systems.

Also, actively seeking the point of muscular failure in Olympic weightlifting movements is dangerous. Unlike traditional bodybuilding movements, the Olympic lifts and their variants are highly explosive movements that are wholly incompatible with the slow-grind-to-failure method of completing a work set.

Bodybuilding: Not Just For Bodybuilders Anymore

Bodybuilding is an unusual sport. Men wearing skimpy trunks on a stage in front of a mostly male audience, covered in oil and fake tan, trying to hide their grimaces with forced smiles, flexing their muscles so hard they look like they’re trying to pass the same stool that killed Elvis.

It’s not everyone’s cup of tea.

Baby oil and homoerotic posing displays aside, bodybuilding has far more in common with what the average trainee does in the gym than Olympic lifting or powerlifting - at least when it comes to training. Bodybuilding and recreational weight training tend to use higher rep ranges, more moderate loads and are primarily focused on improving body composition. The exercises used are a means to an end, typically selected based on their perceived ability to develop a specific muscle grouping.

In Olympic lifting and powerlifting, the competitive lifts are the ends, and accessory exercises are chosen with the goal of improving performance of the main lifts.

This isn’t to say you can’t build an impressive physique via Olympic lifting or powerlifting - you most certainly can. It’s just not the way most people go about it.

In the late 1970s, Mike Mentzer demonstrated that one could indeed rise to the upper echelons of professional bodybuilding using the single set approach. In 1978, the powerfully-built Mentzer won the Mr Universe contest with the first ever perfect score of 300.

British bodybuilder Dorian Yates later took the single set approach to new heights, dominating competitive bodybuilding throughout the 1990s with unprecedented levels of muscle mass and density.

So there is - or should be - no doubt that single set training can produce significant gains in strength and hypertrophy. This has been demonstrated in clinical trials and borne out on the world bodybuilding stage.

What About Powerlifting?

By virtue of its focus on the “Big Three” lifts (bench press, deadlift, squat), powerlifting has more in common with bodybuilding than Olympic lifting does.

Powerlifting isn’t exactly flooded with people citing single set training as the key to their success, but there have been a couple of notable exceptions.

Paul Brodeur, who placed first in the 275+ class at the 1985 USPF Texas state championships with a mighty total of 2105.4 lbs, attributed his success to single set training. In this interview, Brodeur stated that he eventually reduced his training volume and frequency to 1 set to failure with 1 workout every 7-14 days. Not the kind of frequency I’d recommend for the average trainee, but Brodeur wasn’t exactly your average gymgoer.

Joey Almodovar was trained by the late Dr Ken Leistner, an avid proponent of single set training. Almodovar was a highly-ranked competitive powerlifter who squatted 705, benched 402.3 and deadlifted 640 for a total of 1735 lbs in the 165 lb class.

Putting Single Set Training to the Test in Competitive Powerlifters

In 2018, researchers published the results of a study examining the effects of a single set routine on contest preparation for national level powerlifters in Greece.

Ten competitive powerlifters from the Athens AEK powerlifting team were split into 2 groups. During the ten-week lead-up to the Hellenic Powerlifting Federation (HPF)** national championships, one group followed a “daily max” training protocol (MAX) or a traditional periodized training protocol (PER).

The mean stats for the lifters were age 27 years, body mass 90.5 kg, height 178.9 cm. The participants ranged from beginner to intermediate with 2 ± 1 years of powerlifting experience, and 5 ± 2 years of resistance training experience.

Five lifters were assigned to each group. The group assignment process was not randomized; instead, in a process managed by the team’s head coach, participants were paired based upon current performance and then divided evenly between the two groups.

Prior to the training intervention, participants were following a powerlifting program that incorporated moderate training volume and both moderate and high loads (70–90%1RM).

The PER Training Intervention

The PER group performed higher volume training with loads ranging (periodized) from 70%1RM up to 93%1RM.

This training consisted of a 4-week preparatory “mesocycle” where training load was kept around 70–80%1RM, followed by a 4-week transitional mesocycle where training volume remained high and training load slightly increased to 75–85%1RM.

The PER group training protocol ended with a 2-week peaking block were volume decreased and training load reached its highest values (90–93%1RM).

The PER group trained 3 times per week and performed the powerlifts with the following frequency: Squat on day 1 and day 3, bench press on all 3 days, and deadlift on day 2.

Athletes in the PER group performed multiple working sets during every training session. No accessory exercises were performed by the PER group.

The MAX Training Intervention

During the intervention, the MAX group performed single sets of single repetitions using a load equating to a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) of 9–9.5 (i.e., where another repetition could not be performed if attempted, though a slight increase in load might be possible).

Similar to the PER group, the MAX group trained three times weekly and performed deadlifts once per week, squats twice weekly, and bench press on all 3 days.

The MAX group decreased its training sessions to 2 on the week of the competition for recovery purposes, performing the squat and bench at 2 sessions and the deadlift at 1.

Similar to the PER group, the MAX group performed no accessory exercises.

This means that during weeks 1 through 9, the MAX group performed 2 work sets, each for 1 rep, per workout. In week 10, a total of 3 work sets of 1 repetition each per session were performed.

Now that’s some brief training.

The PER group, in contrast, performed 3-15 work sets per exercise and 1-7 reps per set during the 10-week intervention.

All participants underwent 1RM testing for squat, bench press and deadlift before and after the 10-week intervention (1RM = maximum amount of weight able to be lifted for a single repetition in correct form). The post-study 1RM measurements were in fact the lifts achieved at the National Championships.

Baseline 1RM of the participants completing the study ranged between 145-215 kg on the squat, 92.5-145 kg on the bench press, and 155-240 kg on the deadlift.

The Results

Two participants in the PER group suffered minor injuries, one related to the training protocol and the other unrelated, and were excluded from the rest of the training intervention and the data analysis. The remaining eight participants were all included in the data analysis as they successfully completed the training intervention.

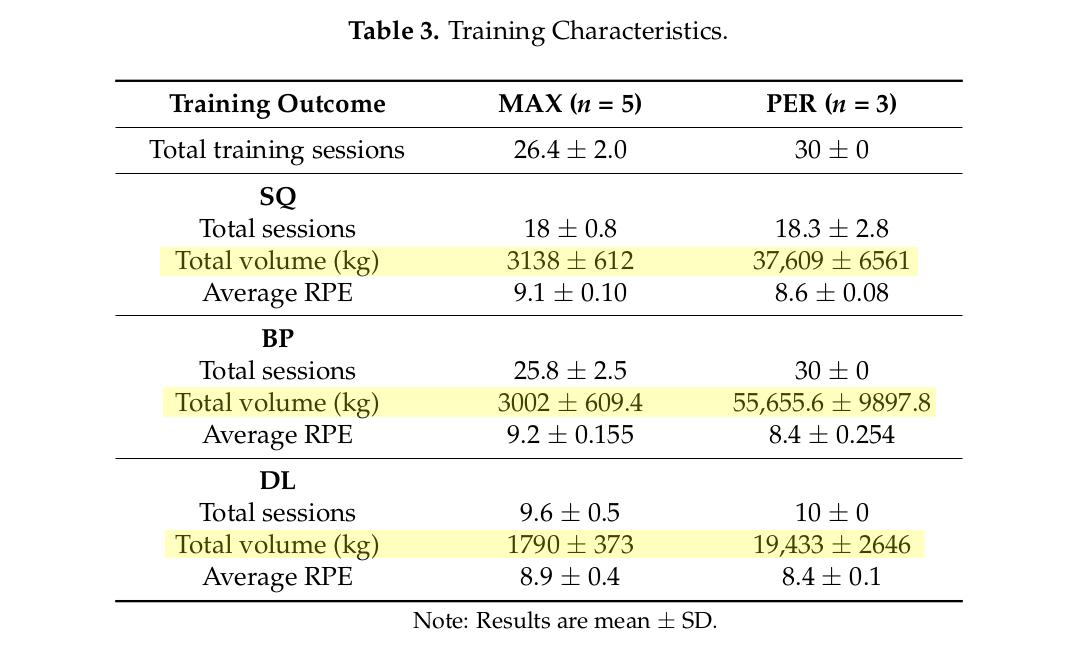

The following table from the paper highlights the stark contrast in training volumes. Depending on the exercise, the PER group performed 11 to 19 times as much volume, in terms of total weight lifted over the 10 weeks.

In the PER group, two of the 3 subjects increased their powerlifting total at the HPF Championships, by 2% (12.5 kg) and 6.5% (35 kg) respectively. The third subject maintained their previous total, for a gain of 0%.

In the MAX group, two of the 5 subjects increased their total at the Championships, by 4.5% (20 kg) and 4.2% (25 kg).

A third subject, who we’ll refer to as MAX3, experienced a slight 0.5% (2.5 kg) decrease.

Subjects MAX4 and MAX5 experienced notable decreases in their competition totals, by -3.4% (20 kg) and -5% (20 kg), respectively.

During the 10-week training intervention, there were only 3 failed “daily max” attempts in the MAX group (2 in the bench press and 1 in the deadlift), which suggests the athletes effectively used the RPE method to select their work set weights.

Let’s take a moment to unpack what we’ve discussed so far.

When the results are averaged out for each group, the PER group achieved a better result. However, two of the participants in that group dropped out due to injury, and one of those injuries was attributed to the training protocol. Two of the remaining subjects improved their total, the other experienced no change.

In the MAX group, two subjects also improved their total, while another experienced a 0.5% decrease. Two more subjects from the single set group experienced significant declines in their Championship totals, but of course we have no way of knowing if a similar fate would have befallen the other two subjects in the PER group because they didn’t complete the intervention.

Now, let’s look at some more results from the study.

The training of the PER group was deliberately structured so that they didn’t go for an all-out max until competition day. So their highest totals during the study were achieved on competition day, at least for the two subjects who saw improvement.

In the MAX group, subjects were instructed to use a 9-9.5 RPE to guide their weight selection during all workouts. On a good day, and a nice caffeine buzz, this could have easily have led to new 1RM PRs being set during the training period leading up to the contest.

And that’s exactly what happened with four of the 5 MAX subjects.

During the ten-week intervention, MAX1, MAX2, MAX3 and MAX4 increased their powerlifting total by 3.6%, 4.2%, 4.5% and 1.8%, while MAX5 decreased his total by 3.2%.

So four out of the 5 MAX participants increased their total, but two of them regressed by the time the competition rolled around.

On the squat, four participants in the MAX group matched or exceeded their subsequent competition 1RM during training. They did this in weeks 8, 9, 6 and 5, respectively.

On the bench press, all 5 MAX subjects matched or exceeded their subsequent competition 1RM. This occurred during weeks 1, 4, 4, 3 and 3.

On the deadlift, 4 of 5 MAX subjects matched or exceeded their subsequent competition 1RM. This happened during weeks 9, 4, 5 and 7.

We can see from these figures that, with the exception of the bench press, there was a fairly wide variation in exactly when the subjects hit their best 1RM.

However, most of the training PRs occurred between weeks 4 to 7.

This is an important observation.

Astute readers will have noticed that set volume was not the only variable tested in this study. While, both groups trained three days per week and performed the same exercises, that’s where the similarities ended. By way of following a periodized routine, the PER group varied the intensity of effort and the repetition range over the 10 weeks. The MAX group, in contrast, did pretty much the exact same thing throughout the 10-week intervention.

This matters. A lot.

You can’t do the same thing, day in, day out, and expect continuous progress - especially when working with near-limit weights. Even chemically-enhanced athletes need to periodize their training for best results.

The researchers themselves noted:

“The weeks where the MAX group achieved its highest SQ and DL numbers imply that a 4–7 weeks training cycle may have been more effective when implementing a “daily max” training approach, at least for the SQ and DL.” (Bold emphasis added)

One common approach, in both strength and endurance sports, is the use of four-week “mesocycles,” where the fourth week is a light week. For years, I recommended clients have a light week every fourth week, and I myself followed a variation of this strategy where I took a complete break from weight training every fourth week (I still cycled and did other activities). During that down week, I’d review the previous weeks’ progress and modify the strategy for the next four weeks accordingly.

It worked well for clients, and I personally used this method to steadily build up to a deadlift of 2.5 times my body weight back in 2015.

I still use a similar method, but with a slight change. Instead of strictly assigning a full week break to be taken every fourth week, I train until I see my progress - measured in terms of weight increases on my lifts - stalling or regressing. I then take a week off. Instead of a nine-day break, I will return to the gym 7 days after my last workout. For example, if I realize I need time out on a Wednesday, I’ll return to the gym the following Wednesday.

When following a single-set, whole-body protocol, I find the need for a break usually occurs around 4-6 weeks of continuous training.

Basically, I’m waiting for the earliest signs of overtraining, then taking a break.

This might not be the most sophisticated way of ‘periodizing’ one’s training, but I submit that it is a far more realistic, manageable and hassle-free approach for the the majority of people. Most folks do not have the time nor inclination to draft complex spreadsheets of their training, with an array of percentages, rep ranges and set numbers that would make a mathematician’s head spin.

I believe this approach to periodization is also more effective than what is recommended by most “HIT” practitioners, which is either 1) no periodization at all, or 2) taking increasingly longer breaks between workouts whenever your progress stalls, until you are training only once every seven days (and wondering why you are looking even smaller and smoother).

Those of us who benefit from single set training owe a debt to the late Mike Mentzer, who did much to popularize brief, intense training. In his later years, however, Mentzer went from recommending thrice-weekly training - the kind he used to build his championship physique - to prescribing routines where one trained only once every 4-7 days. Judging from his book Heavy Duty II, the latter recommendation appears to be based on a ‘revelation’ he had when training a young lad called Racy, a personal training client whose progress had stalled.

Mentzer reduced Racy’s workout volume and frequency to only three sets per workout every 5 to 7 days. “Racy started growing stronger and bigger,” recalled Mentzer, “although his progress was never dramatic.”

Convinced reduced frequency was the key to progress, Mentzer began “reducing the average client's baseline from 7-9 sets every 48 hours to only 3-5 sets every 72 hours.”

“It wasn't long, however, before I grew disillusioned once again,” wrote Mentzer. “While the majority did better than before, I again had no doubt that they could, or should, do better still, and progress always slowed down considerably after two to three months.”

Quoting Ayn Rand instead of exercise science, Mentzer dug his heels in even further. “I suggest you start training once every four days, every 96 hours,” he wrote in Heavy Duty II. This remember, was on a split routine, not a full body routine.

What Mike didn’t realize was that his clients needed periodic breaks, not progressively longer gaps between every workout. He mistook the initial benefits from a reduction in frequency as a sign that his clients needed to take progressively longer breaks between workouts.

Brief, Intense ... and Periodized

The Greek powerlifter study suggests single set training does yield potential for use among competitive strength athletes, but serious thought needs to be given to how such training can be best periodized. The majority of lifters in the MAX group did indeed achieve new PRs, only they achieved them early, with two lifters noticeably regressing by contest time.

MAX3, the subject whose total declined by 0.5% at contest time, had in fact gained 20 kg (12.5%) on his max deadlift at week 4 - an impressive increase in a relatively short time. At the contest, however, the gain had diminished and he could only deadlift his baseline PR.

Had the MAX group’s routine been programmed so that the early gains were consolidated with a scheduled break or decrease in intensity, before being built upon with another period of max training, the outcome may have been very different.

The topic is crying out for more research, but whether that happens remains to be seen. The authors of the Athens study concluded that the near-limit, single set training protocol was good for short-term gains, but that the higher-volume periodized training appeared superior in the long-term. What we need are more studies investigating protocols that combine single set and periodized training.

Interestingly, when asked during a 2016 seminar what he would have done differently during his bodybuilding career, Dorian Yates replied “I would cycle the intensity properly, I would listen to my body more … instead of being gung-ho and just pushing through it all the time” (53:41 of this video).

He specifically stated he would back off on the intensity during a contest phase where fat loss is the focus, calorie intake is lower, and the potential for injury is hence higher.

In Summary

This small study with competitive powerlifters confirmed that single set training can produce quick gains in strength, and strongly suggests that successful longer-term application of this method requires periodization or cycling of intensity.

The study also shows that the quick gains in strength occurred with only a fraction of the total volume and training time required by conventional, higher volume training.

This greatly reduced workout time would have allowed the addition of assistance exercises, which may have further benefited the MAX athletes’ totals.

To date, the discussion around single set training has often been a highly polarized one. Like so many topics, people adopt a side and then defend it zealously, using ridicule and vitriol to attack those with opposing viewpoints.

Which is a pity, because not only does single set training work, it does so in a fraction of the time required by the conventional high volume training approach.

*HIT, or H.I.T. is not to be confused with high intensity interval training (HIIT), which refers to abbreviated cardiovascular training with intermittent bouts of intense ‘sprints’; the term H.I.T. was coined by Ellington Darden (an employee of Arthur Jones). The term “Heavy Duty” was popularized by Mike Mentzer.

**The HPF is the Greek affiliate of the International Powerlifting Federation.

Leave a Reply