Will caffeine boost your performance in the gym?

The beneficial effect of caffeine on endurance performance is well-established. But what about training in the gym?

Will caffeine increase your maximal strength? Will a double-shot prior to a workout have you setting new PRs on the squat, deadlift and bench press?

Will it increase the number of repetitions you can do with a given weight?

What about the effects of regular use? Will using caffeine over the longer term improve your training results?

Let’s find out.

The content below was originally paywalled.

The Acute Effects of Caffeine on 1RM and Muscular Endurance

The ultimate test of strength is the one-rep maximum (1RM). This is the maximum amount of weight you can lift for a single repetition on a given exercise.

The ultimate example of a 1RM is when an Olympic lifter like Karlos Nasar hoists ungodly amounts of weight above his head to win a gold medal, or when a powerlifter like Dan Grigsby pulls the equivalent of an adult horse from the floor to set a new deadlift record.

If your 1RM increases over time, then you know your absolute strength has increased.

Along with increases in weight, the other primary marker for improved performance in the weight room is being able to perform more repetitions with the same weight. In clinical studies with caffeine, researchers often get subjects to perform as many reps as possible with a given % of 1RM, often in the vicinity of 60-80%. An increase in the number of repetitions performed at these lower intensities is dubbed an improvement in muscular endurance.

Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been performed on this topic, with several stating caffeine enhances both 1RM and muscular endurance. As you’re about to learn, the truth of the matter is not so clear cut.

The problem with systematic reviews and meta-analyses is that they pool together the results of multiple studies and spit out an average percentage or effect size, which is then deemed representative of the research as a whole. That’s fine when the clinical studies in a field all tend to point in the same direction, but when you have studies with disparate results, it can be downright misleading.

It is beyond the scope of this article to dissect every single RCT that examined the effect of caffeine on 1RM and/or muscular endurance. What I will do here is discuss a sizable cross-section of the research, which should impress upon readers that the findings in this field are anything but homogeneous.

In the first part of this article, I’ll focus on placebo-controlled crossover studies that examined caffeine’s acute effect on 1RM and muscular endurance using free weights or machine exercises such as the leg press.

Why crossover studies? Because in a crossover study, all the subjects receive both intervention and placebo on separate occasions, in random order. This differs from the way longer-term clinical trials are usually performed, where you have two groups randomized to receive either the active intervention or a placebo for a set period of time. Due to time constraints, this is often the only practical way to conduct such studies, especially when they extend beyond several months. However, in studies examining the acute effects of supplements or drugs, the crossover format is preferable because every subject acts as their own control. This gives us greater confidence that any difference between treatment and placebo is real and not just an artifact of differences between the groups (e.g., one group may feature individuals with greater training experience, or with a genetic predisposition to respond more favorably to the treatment, and so on).

The earliest relevant crossover study I could find was Jacobs et al 2003, in which 4 mg/kg anhydrous caffeine was taken 90 minutes prior to a weight-training test consisting of three “supersets” of back-to-back squats and bench presses to failure. Two minutes of rest was allotted between each superset.

Compared to placebo, caffeine produced no improvement in the mean number of repetitions for leg press or bench press during any of the supersets.

The subjects were 13 recreationally active males. Usual dietary caffeine intake in the subjects was not queried, other than to confirm none of the subjects avoided caffeine ingestion.

Caffeine wasn’t off to a good start with this study, but it should be noted consuming caffeine 90-minutes before a workout may result in peak blood caffeine levels declining by the time you hit the iron. This is why most other studies allow a 60 minute window prior to exercise testing, and rarely less than 30 minutes.

Astorino et al 2008 is another oft-quoted early crossover study. It involved twenty-two resistance-trained men, with a self-reported training frequency of at least twice per week and a mean training history of six years. The subjects were classified as mild habitual caffeine users with a daily intake of less than 3 mg/kg.

The study found no significant improvement in 1RM bench press or leg press after ingesting 6 mg/kg of caffeine 60 minutes prior to testing.

When tested at 60% 1RM, subjects performed a mean 1.5 and 1.4 reps more on the bench press and leg press, respectively, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Williams et al 2008 found no improvement in bench press and lat pulldown 1RM or 80% 1RM muscular endurance 45 minutes after ingestion of 300 mg caffeine, 60 mg ephedrine, or both. The subjects were 9 healthy young resistance-trained males.

Habitual caffeine intake was not closely examined. According to the researchers, “Preliminary diet sheets submitted by many of the participants indicated that their habitual caffeine intake was low, for example, one cup of coffee per day. None of the subjects appeared to be heavy users.”

Woolf et al 2009 involved seventeen highly-trained collegiate football athletes who were low caffeine users. They ingested 5 mg/kg caffeine or placebo then completed 3 exercise tests (40-yard dash, 20-yard shuttle, and bench press reps-to-failure) 60 minutes later. The bench press test used a fixed weight of 185 or 225 lb, depending on the subject’s baseline strength.

Overall, caffeine did not improve any of the tested outcomes. The researchers did note, however, that 59% of participants showed improved performance during the bench press and the 40-yard dash after caffeine ingestion. This suggests individual variation in response to the same relative caffeine dose.

Habitual caffeine use in this group was low, with a typical caffeine intake of 16 mg per day. Only one participant consumed greater than 50 mg/day (= 81 mg).

Duncan et al 2013 had eleven resistance-trained individuals (9 males, 2 females) ingest 5 mg/kg caffeine or placebo 60 minutes before a bout of resistance exercise. Average habitual caffeine intake of the subjects was 211 mg/day, with a range of 120-400 mg/day.

The exercise sessions consisted of bench press, deadlift, prone row and back squat to failure at 60% 1RM.

So while most studies examined the effect on 1 or 2 resistance exercises, this study featured four exercises, more closely resembling an actual workout.

Participants completed more repetitions to failure in the caffeine compared to placebo condition. When all exercises were combined, mean repetitions to failure were 19.7 and 18.6 in the caffeine and placebo conditions, respectively. The difference was statistically significant.

However, improvement in bench press performance - the first exercise to be performed - accounted for the bulk of the difference. The order of exercises during the sessions was bench press, deadlift, prone row and back squat. Eight of 13 participants revealed a meaningful increase in bench press repetitions to failure with caffeine ingestion, compared to 6 of 13 for the prone row and 5 of 13 for both the deadlift and back squat. This suggests that, after bench-pressing to failure, the effect of caffeine diminished. This pattern of a benefit confined to the beginning stages of testing can be seen in other studies below.

Richardson and Clarke 2016 compared the effects of caffeine anhydrous, coffee, or decaffeinated coffee+anhydrous caffeine taken prior to resistance exercise

After a familiarization session, nine resistance-trained men completed a squat and bench press exercise protocol at 60% 1RM until failure on 5 occasions. All subjects were required to be resistance training 3–4 times a week and to have included bench press and squat pattern exercises in their workouts for at least 1 year prior.

Average habitual caffeine intake of the subjects was 241 mg/day.

Sixty minutes before each test session, the subjects consumed either a caffeine anhydrous supplement, Nescafé Original coffee, Nescafé decaffeinated coffee, Nescafé decaffeinated coffee+caffeine anhydrous, or placebo. Apart from the placebo and decaffeinated only conditions, all beverages were measured out to contain 5 mg/kg caffeine.

The number of repetitions performed for the squat in each of the conditions was as follows:

Nescafé decaffeinated coffee+caffeine anhydrous: 18

Nescafé Original coffee: 17

Caffeine anhydrous supplement: 15

Nescafé decaffeinated coffee: 14

Placebo: 13

As a result of the greater repetitions achieved, subjects lifted a significantly greater total weight (load x repetitions) after ingesting the regular coffee and decaf + caffeine anhydrous beverages.

There were no significant differences between conditions in number of repetitions performed or total weight lifted in the bench press protocol.

When the total amount lifted from both exercises was combined, 5 of 9 subjects lifted their greatest total weight during the decaf+caffeine anhydrous condition, while the remaining 4 lifted their greatest total weight during the regular coffee condition.

Grgic & Mikulic 2017 administered 6 mg/kg caffeine to 20 resistance-trained men, 60 minutes prior to exercise testing. After a warm-up, muscle power was tested using the vertical jump test and seated medicine ball throw test. This was followed by back squat, for which subjects worked up to a 1RM. After a 5-minute rest, they then knocked out as many reps as possible with 60% RM. To assess upper body strength, this same procedure was then repeated on the bench press.

Compared to placebo, caffeine intake enhanced 1RM back squat performance (+2.8%) and seated medicine ball throw performance (+4.3%). There were no other statistically significant differences between conditions for any other strength, power or muscular endurance outcome.

The participants reported an average caffeine intake of 58 mg per day, with 10 participants reporting no regular caffeine intake.

Wilk et al 2019 involved sixteen strength-trained male team sport athletes in their twenties. The subjects had a mean 4.1 years of strength training experience and bench press 1RM of 118.3 kg. Furthermore, all the subjects were high habitual consumers of caffeine, with a mean daily intake of 4.9 mg/kg.

During the three experimental sessions, participants either ingested a placebo, 9 mg/kg caffeine, or 11 mg/kg caffeine. Sixty minutes later, they performed a 1RM bench press test, followed by a muscular endurance test on the bench press using 50% 1RM.

The data shows a mean 4 and 6 kg increase in 1RM with the 9 and 11 mg/kg doses, respectively, but they were not statistically significant. The mean number of repetitions achieved with 50% 1RM was near-identical between all 3 treatments.

Not surprisingly, the 9 and especially 11 mg/kg doses were associated with a high rate of side effects. During the session and 24 hours after both caffeine treatments, the majority of subjects experienced tachycardia/heart palpitations, and anxiety or nervousness. Increased urinary output, insomnia, gastrointestinal problems, and headache were also commonly reported.

Many researchers have shied away from examining the acute effects of caffeine in female subjects, out of concerns the menstrual cycle would confound the results. However, Sablah et al 2015 recruited 10 males and 8 females to determine the effect of 5 mg/kg caffeine on bench press and squat 1RM, and number of bench press reps to failure at 40% 1RM (reported as reps x weight = total weight lifted).

The subjects were moderately trained with over 1 year of resistance training. The paper notes all participants were habitual caffeine drinkers, but provides no further details on typical daily intake.

Order of testing was bench press 1RM, squat 1RM then BP endurance. Bench press 1RM was significantly greater with caffeine for both genders; an increase of 5.9% for males from 101.5 to 107.5 kg and an increase of 10.7% from 32.2 to 35.3 kg for females.

Caffeine did not improve squat 1RM in either gender.

In males, caffeine resulted in an increase in bench press reps to failure with 40% 1RM and hence a 23.96% increase in total weight lifted (increase for males from 1,246.8 to 1,545.5 kg). In females, caffeine did not increase the total amount lifted compared to placebo (398.8 vs 397.8 kg, respectively).

Grgic et al 2020 used twenty-eight resistance-trained men to compare the effect of 2, 4, and 6 mg/kg caffeine doses. Testing comprised of 1RM and repetitions to failure with 60% 1RM on the bench press, followed by the same protocol for the back squat.

Subjects were required to have a minimum of one year’s resistance training experience with a minimum training frequency of twice weekly, and; have the ability to perform the bench press and back squat with a load corresponding to at least 100% of their body mass. Based on questionnaires completed by the subjects, the mean habitual caffeine intake of the sample was 112 mg/day.

Compared to placebo, the 2, 4 and 6 mg conditions resulted in -0.5, +0.9 and +1.4 kg differences on bench press 1RM - however, none of these were statistically significant.

For the squat, the 2 mg/kg condition produced a statistically significant increase in 1RM (+3.0 kg), but not the 4 or 6 mg/kg conditions (+1.6 and +1.5 kg, respectively).

None of the conditions produced any statistically significant increase in reps-to-failure with 60% 1RM on the bench press.

However, for the squat, 2 mg/kg of caffeine (+4.8 repetitions), 4 mg/kg (+3.9 reps) and 6 mg/kg (+4.5 reps) acutely enhanced muscular endurance to a statistically significant degree.

Filip-Stachnik et al 2021 recruited twenty-one healthy resistance-trained female students with a high daily caffeine intake of 5.8 mg/kg.

The treatments were placebo, 3 mg/kg caffeine and 6 mg/kg caffeine, consumed 60 minutes before testing for bench press 1RM and reps to failure with 50% 1RM.

Caffeine produced a statistically significant increase in bench press 1RM. Maximum lifts after ingestion of placebo, 3 mg/kg caffeine and 6 mg/kg caffeine were 40.48 kg, 41.68 kg and 42.98 kg, respectively.

Repetitions to failure in the placebo, 3 mg/kg caffeine and 6 mg/kg caffeine conditions were 33.05, 33.81 and 35.29, respectively, with no statistically significant difference between treatments.

Jones et al 2021 featured fourteen strength-trained females using hormonal contraception. “Strength-trained” was defined as performing resistance-training at least 3–5 days per week for the 6-month period immediately prior to the study. Mean habitual intake of the subjects was 109.7 mg/day.

Thirty minutes prior to testing, the subjects received 3 mg/kg caffeine, 6 mg/kg caffeine, or placebo. After a warm-up, the subjects worked up to a 1RM on a Hammer Strength leg press machine, followed by repetitions to failure at 60% 1RM.

Neither caffeine dose increased 1RM. Four of the 13 subjects achieved their highest 1RM after placebo, 3 after 3 mg/kg caffeine, 5 after 6 mg/kg, while another subject lifted the same 1RM under all three treatments.

However, muscular endurance and total weight lifted were increased to a statistically significant degree after ingestion of caffeine. Mean repetitions achieved with 60% RM during the placebo, 3 mg/kg caffeine and 6 mg/kg caffeine conditions were 35.5, 43.7 and 48.2, respectively.

Karayagit et al 2021 also featured an all-female sample, with 17 resistance-trained and mostly national-level team sport athletes who reported consuming less than <25 mg/day caffeine. Before the testing sessions, the subjects ingested 3 mg/kg or 6 mg/kg caffeine from from Nescafé Gold, or Nescafe decaffeinated coffee.

An hour after finishing their beverages, the subjects warmed up, then performed three sets to failure on the squat using 40% 1RM, resting 2 minutes between sets. After a five-minute rest, they performed 3 sets of the bench press using the same protocol.

After ingestion of either coffee dose, the subjects were able to knock out a couple of extra reps on the first set of the squat. No effect was seen on subsequent sets. During the first set of squats on placebo, 3 mg/kg caffeine and 6 mg/kg caffeine, the subjects performed 31.2, 33.4 and 33.9 reps, respectively. This equates to a 7-8.7% increase in first set rep count compared to placebo.

When it came to the bench press, a non-significant 3.1% increase in the first set rep count was seen when compared to placebo. Again, no difference was seen on subsequent sets between any of the conditions.

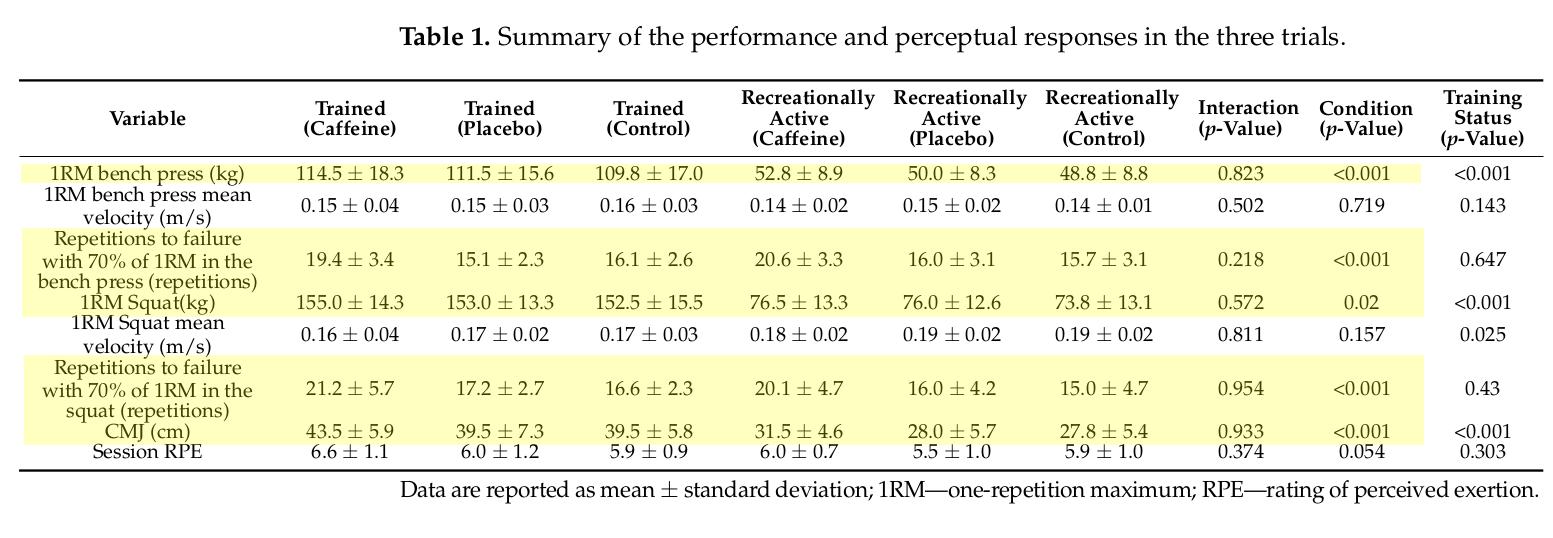

There has been some debate as to whether the ergogenic response to caffeine is moderated by one’s training status. To gain further insight into this question, Berjisian et al 2022 recruited 10 trained and 10 recreationally active subjects, all males. To qualify as “trained,” subjects had to be regularly training 3 or more times per week with the purpose of competing in a specific sport (i.e., bodybuilding, volleyball, soccer); able to perform the 1RM squat with a load at least 1.5 times their body weight and a 1RM bench press with a load at least equal to their body weight. The ten trained participants had a minimum of 5 years’ resistance training experience, regularly performing this type of exercise 4 or more hours per week.

The recreationally active participants had less than six months of resistance training experience and performed 3 or fewer hours of this type of activity per week.

Participants reported low habitual caffeine consumption (<50 mg/day).

All subjects consumed 6 mg/kg caffeine anhydrous 60 minutes, placebo, or no treatment before the three testing sessions. The sessions comprised a warm-up, followed by 1RM testing on the Smith machine bench press. The same exercise was then performed to failure using 70% 1RM. This procedure was repeated for the Smith machine squat, after which subjects were tested on the countermovement jump.

Irrespective of their training status, caffeine produced statistically significant increases in squat and bench press 1RM, squat and bench press repetitions to failure with 70% of 1RM, and countermovement jump height (see table below).

Montalvo-Alonso et al 2024 is one of the larger studies on this topic. Seventy-six resistance-trained individuals (38 females, 38 males) with a high average habitual caffeine intake of 5.6 mg/kg/day participated.

Compared to placebo, ingestion of 3 mg/kg caffeine 60 minutes before testing increased the number of reps attained in both the bench press and squat using 65% of 1RM. For the bench press, the number of reps increased by 8.1% and 6.0% in males and females, respectively. For the back squat, the rep counts increased by 8.9% and 7.9% in males and females, respectively.

After caffeine ingestion, isometric handgrip strength in the dominant hand was increased in males only (3.1%). No effect was found for isometric handgrip strength in the non-dominant hand, the isometric mid-thigh pull test or the countermovement jump.

Montalvo-Alonso et al 2025, meanwhile, found 3 mg/kg of caffeine increased muscular endurance performance at 65%1RM in back squat, but not in the bench press.

Scapec et al 2024 involved 29 resistance-trained participants (11 men and 18 women) who ingested placebo, caffeine (3 mg/kg), paracetamol (1500 mg) or caffeine + paracetamol 45 min before testing sessions.

Participants had a minimum of 1 year’s training experience; habitual caffeine intake of the subjects was not mentioned.

Caffeine increased the number of bench press repetitions to failure with 75% 1RM. The rep counts for the various conditions were: Caffeine 14.3; caffeine+paracetamol 13.8; paracetamol 13.4; placebo 13.1.

There was no improvement in a Wingate sprint test nor in the countermovement jump.

Tallis et al 2024 evaluated the effect of 3 mg/kg caffeine delivered in anhydrous form via capsule ingestion, chewing gum or mouth rinsing on measures of muscular strength, power, and strength endurance in male Rugby Union players.

Twenty-seven participants from Coventry University Men’s Rugby Union completed the study. Self-reported average daily caffeine consumption was 188 mg, with eight participants reporting no caffeine use.

Encapsulated caffeine was ingested with 150 ml of water 45 minutes prior to exercise. Caffeine chewing gum was administered 10 minutes prior to exercise, chewed for 5 minutes. Caffeine rinsing was undertaken 1 minute prior to exercise, with participants washing the solution around the mouth for 30 seconds and then spitting it into a waste bucket. Placebo treatments were administered in the same way.

Testing sessions included chest press, shoulder press, deadlift, and squat, each performed for 3 sets to failure. None of the caffeine treatments had any noteworthy effect on rep count.

The treatments did show a small effect on countermovement jump height, with mean improvements for the 3 caffeine treatments ranging from 0.7-1.8 cm.

Ding et al 2025 recruited sixteen resistance-trained young men with a mean training history of 4.4 years. At baseline, their mean 1RM bench press and back squat was 99.7 kg and 154.7 kg, respectively. The subjects self-reported a habitual caffeine intake ranging from 0–3 mg/kg/day.

At the testing sessions, participants engaged in a 10-minute general warm-up, then chewed either placebo or caffeinated chewing gum for 5 minutes before beginning 1RM and 60% 1RM repetitions to failure tests for the bench press and back squat.

Compared to the placebo gum, caffeinated chewing gum significantly increased 1RM for both bench press (105.3 versus 100.3 kg, +5.0%) and and back squat (172.3 versus 161.9 kg, +6.8%).

Caffeinated chewing gum also increased the number of repetitions for both bench press (20 versus 17) and back squat (37 versus 28).

A Quick Summary of What We’ve Learned So Far

I recently watched a YouTube video about caffeine by an online coach and powerlifter, who generally gives sensible advice. A self-confessed caffeine addict, he stated in his video:

“I really do think caffeine is like a miracle drug for strength and power performance.”

I love my coffee, but after reading the research above, it would be irresponsible for anyone to claim caffeine is a “miracle” drug. A miracle drug would produce clear and pronounced benefits for pretty much everyone, every time, with an absence of side effects. When it comes to resistance exercise, the science shows that just isn’t the case with caffeine.

Even if your habitual caffeine use is low, I could carefully measure out 3-6 m/kg caffeine anhydrous, give it to you precisely 60 minutes prior to a workout, and not be able to predict with any certainty what would happen in terms of your strength or muscular endurance.

Some studies found no benefit from caffeine. Others hinted at a benefit, but the results didn’t attain statistical significance, perhaps due to the small sample sizes that plague research in this field.

Some studies found an increase in 1RM, but not repetitions to failure with submaximal weights. Others found an increase in reps to failure with submaximal weights, but no improvement in 1RM.

One study found an increase in reps to failure but not countermovement jump height. Another study found no increase in reps to failure, but an increase in countermovement jump height.

One of the above studies found 5 and 6.8% increases in 1RM bench and squat, respectively, after chewing caffeinated gum - impressive differences in trained lifters. However, another study found no effect of caffeinated chewing gum on 1RM.

In studies achieving positive findings and involving multiple exercises, or multiple work sets to failure of the same exercise, there was a general pattern of benefits being most pronounced in the initial exercise or the initial work set. This stands in stark contrast to caffeine’s well-established ability to increase time-to-exhaustion in studies examining aerobic endurance.

In some studies, low habitual caffeine users experienced benefits, in others they experienced little-to-no benefit.

Gender also did little to alter the now-you-see-them, now-you-don’t nature of caffeine’s strength and muscular endurance effects.

So caffeine’s acute effect on strength and muscular endurance in the gym is hardly a model of consistency. But what happens when caffeine is used prior to workouts on a regular basis? Does this have any long-term effect on strength gains and/or body composition?

Considering caffeine’s popularity as an ergogenic, surprisingly few studies have examined this issue. Let’s take a look at the ones that did. Being longer-term endeavors, most of these studies were parallel arm RCTs featuring separate intervention and placebo groups.

Pre-Exercise Caffeine Over the Longer term

Kemp et al 2012 is the first English-language study that seems to have explored the longer-term use of caffeine on resistance training outcomes. Fourteen healthy male volunteers (18-25 years) with previous strength training experience took part in the study. The mean duration of training experience is not provided. All but two participants self-reported drinking less than 2 cups of coffee per week, while the remaining 2 reported consuming less than 100 mg caffeine daily.

After baseline testing to determine their bench press and squat 1RM, participants were randomly assigned to the caffeine or placebo group.

All subjects performed a six-week resistance training program, 3 times weekly. Sixty minutes prior to each session, the caffeine group received 3 mg/kg caffeine in the form of crushed NoDoz tablets, while the placebo group received the equivalent volume of crushed Glucodin (glucose) tablets.

The workouts consisted of squats, deadlifts, bench press and bench pulls, performed for four sets to failure with approximately 80% 1RM. The order of exercises was rotated every workout to avoid one exercise always coinciding with peak blood caffeine concentrations.

After training sessions, all subjects received a drink containing 18 g protein and 36 g carbohydrate.

After six weeks, bench press 1RM increased by 7.2 and 12.9 kg in the placebo and caffeine groups, respectively.

Squat 1RM increased by 11.5 and 27.5 kg in the placebo and caffeine groups, respectively.

The caffeine group clearly experienced greater mean gains in bench and especially squat 1RM, leading the researchers to suggest “Athletes looking to accelerate strength gains during training may benefit from regular ingestion of moderate dosages (3 mg.kg-1 body mass) of caffeine.”

Joy et al 2016 reported favorable results from a caffeine-containing supplement, but a couple of caveats are in order. The supplement used in the study supplement (a product called “TRT”) consisted of “150 mg ancient peat and apple extracts, 180 mg blend of caffeine anhydrous and pterostilbene-bound caffeine, and 38 mg B vitamins.”

So the study was not examining the effect of caffeine in isolation, but as part of a multi-nutrient supplement, which introduces extra and potentially confounding variables.

Further, the study was sponsored by VDF FutureCeuticals Inc. - the same company that produced the TRT supplement.

Twenty-one healthy, resistance-trained, male subjects (mean age 27.2) completed the study. Each subject was required to be capable of lifting 1.5 x body weight in the squat and deadlift and 1 x body weight in the bench press. Habitual caffeine intake was not reported.

The subjects performed a periodized training program, 3-4 times per week depending the phase. The supplement or placebo was taken 45 minutes prior to workouts on training days, or at a similar time on rest days.

Before-and-after cross-sectional area and muscle thickness measurements were obtained only for the rectus femoris muscle in the thigh. After twelve weeks, cross-sectional area of the rectus femoris reportedly increased to a greater degree in the TRT group (+1.07 cm2) versus placebo (−0.08 cm2).

A similar finding was reported for rectus femoris muscle thickness (TRT +0.49 cm; placebo +0.04 cm).

However, no differences in lean soft tissue accumulation were seen between groups for any of the sites measured (trunk, left and right leg, left and right arm).

Strength outcomes were not reported.

The researchers concluded “Supplementation with a combination of extended-release caffeine and ancient peat and apple extracts may enhance resistance training-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy without adversely affecting blood chemistry,” but it’s hard to get excited from such minimal results after three months of dedicated training.

Other researchers have not been able to produce favorable results from long-term caffeine use.

Giráldez-Costas et al 2021 featured sixteen healthy participants (12 men and 4 women) who underwent a Smith machine bench press training protocol for 4 weeks (12 sessions), 3 times weekly. Seven participants ingested a placebo and nine participants ingested 3 mg/kg caffeine before each training session.

The subjects were low habitual caffeine consumers, ingesting less than 1 mg/kg caffeine daily at baseline.

Three days before, and 3 days after the completion of the training protocol, participants performed 1RM bench press and force-velocity tests (from 10 to 100% 1RM).

After four weeks, the caffeine group showed greater improvements in mean barbell velocity, but this did not translate into any discernible effect on actual bench press 1RM. The placebo and caffeine groups increased their mean bench 1RM by 6.19 and 7.63 kg, respectively.

Pakulak et al 2021 examined the effects of caffeine and creatine supplementation, alone and in combination, during 6 weeks of resistance training in trained young adults. To qualify for the study, subjects must have been training more than 3 x a week for at least 6 months prior to the start of the study.

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of four groups:

creatine + caffeine (0.1 g/kg/day creatine monohydrate + 3 mg/kg/day caffeine anhydrous)

caffeine (3 mg/kg/day)

creatine (0.1 g/kg/day)

placebo

Mean habitual caffeine intake ranged from 60 mg/day in the caffeine-only group to 155 mg/day in the creatine-only group.

On training days, participants consumed their assigned treatment 60 minutes prior to exercise. On non-training days, participants were instructed to refrain from consuming the supplements.

Participants were assigned the same resistance training program for 6 weeks. The program comprised four sessions per week, with major muscle groups targeted once per week.

Of the 41 participants who were randomized, 28 completed the study (18 males, 10 females).

Before-and-after muscle thickness measurements were attained via ultrasound at several sites (knee extensors, knee flexors, elbow flexors, elbow extensors, total body).

After eight weeks, only knee extensors muscle thickness increased to a statistically significant degree (10.8%), and only in the creatine-only group.

All groups increased their 1RM and reps-to-failure at 50% 1RM on the chest press and leg press, with no differences between groups.

Changes in body composition were unremarkable; Females supplementing with creatine + caffeine experienced a decrease in body mass (pre 80.55 kg, post 79.17 kg) and males on creatine had an increase in body mass (pre 79.01 kg, post 81.74 kg).

One possible explanation for the lackluster effect of creatine was the lack of a loading phase and the intermittent dosing schedule (4 instead of 7 days per week).

Tamilio et al 2021 involved thirty resistance-trained university-standard male rugby union players with moderate habitual caffeine consumption (mean 118 mg/day).

The subjects completed a 7-week resistance training program (2 sessions per week; 2 sets to failure of squat, deadlifts, chest press, seated shoulder press, power clean, hang clean at 70% 1 RM, sit-ups and press-ups without any external load).

Forty-five minutes prior to each training session, subjects consumed either 3 mg/kg caffeine or a placebo.

After seven weeks, the caffeine group showed favorable changes in peak torque and total work performed on specialized isokinetic equipment. However, as with the Giráldez-Costas study, this did not translate to any 1RM improvement on the free weight movements. The caffeine and placebo groups improved their 1RMs on the squat, deadlift, chest press, seated shoulder press, power clean, and hang clean to a near-identical degree.

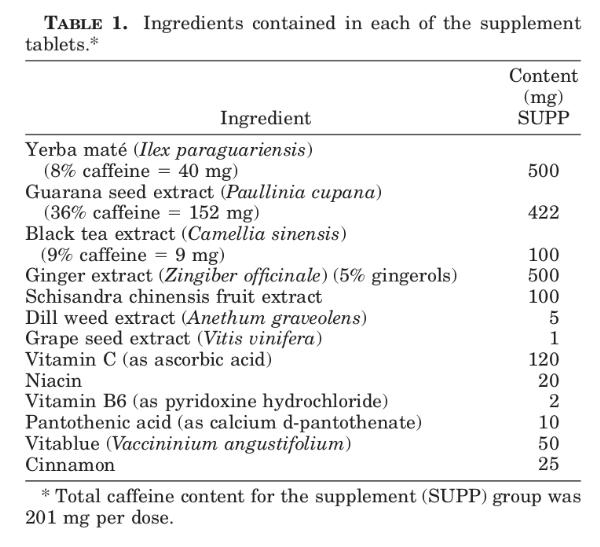

Despite caffeine’s popularity for enhancing endurance performance, I could find only two RCTs that examined its longer-term effects in this regard. Malek et al 2006 examined the effects of daily administration of a supplement that contained caffeine - and several other nutrients (see below) - in conjunction with eight weeks of aerobic training on V̇O2peak, time to running exhaustion at 90% V̇O2peak, body weight, and body composition.

Thirty-six college students (14 males, 22 females; mean age 22.4 years) who had been performing less than 4 hours weekly of regular, continuous aerobic exercise were randomized to either the supplement or placebo.

Habitual caffeine consumption of the subjects prior to the study ranged between 0 and 243 mg/day.

All subjects participated in an endurance training program consisting of 45 minutes of treadmill running, three times per week for 8 weeks.

The subjects ingested their dose of supplement or placebo 60 minutes prior to exercise sessions on training days, and in the morning prior to breakfast on non-training days.

The caffeine-containing supplement had no effect on outcomes after eight weeks. Both groups experienced similar increases in V̇O2peak and time to exhaustion as a result of the training.

Little change was seen in either group for body weight or body composition.

Beaumont et al 2016 set out to determine whether the ergogenic effects of a daily dose of caffeine would diminish over time. Eighteen recreationally active young men, who were low-habitual caffeine consumers (<75 mg/day), were randomly assigned to ingest caffeine or placebo for 28 days.

During the first 7 days of supplementation, the caffeine group ingested 1.5 mg/kg caffeine. Strangely, from days 8 to 28, the caffeine group received 3 mg/kg, equally divided between morning and afternoon (1–3 pm) capsules. The researchers state this titrated approach was designed to minimize side effects in the caffeine-naive individuals (e.g., jitteriness, disturbed sleep, etc). However, no explanation is given as to why the entire dose was not taken 60 minutes prior to the morning exercise testing sessions. Providing an afternoon dose of caffeine to low habitual users would have served little purpose except to potentially disrupt their nightly sleep.

Subjects performed graded stationary cycling tests before, during (day 21) and after the 28-day trial. The “before” tests for every subject included a familiarization test, then the same test performed with caffeine or placebo, in random order. The paper states 3 mg/kg caffeine was consumed the day of the pre- and post-trial (day 29) caffeine tests; the day 29 dose is described as “acute” so presumably both pre-and post-trial test doses were consumed in a single pre-exercise serving.

Performance was assessed solely as the maximum amount of external work that could be completed in 30 minutes. This metric is measured in joules or kilojoules, and calculated based on the power output (in watts) and the duration of the effort.

In both groups, external work was greater during the pre-trial tests where caffeine was ingested. Chronic caffeine supplementation resulted in a mean 7.3% decrease in total external work produced on day 29 compared to the pre-trial test with caffeine.

Total external work produced by the caffeine subjects during the day 29 trial was slightly but not statistically higher than the pre-trial placebo test (358 versus 344.9 kJ). From this, the researchers inferred a “possibly beneficial” effect and that chronic caffeine supplementation might have not completely eliminated the initial performance benefit.

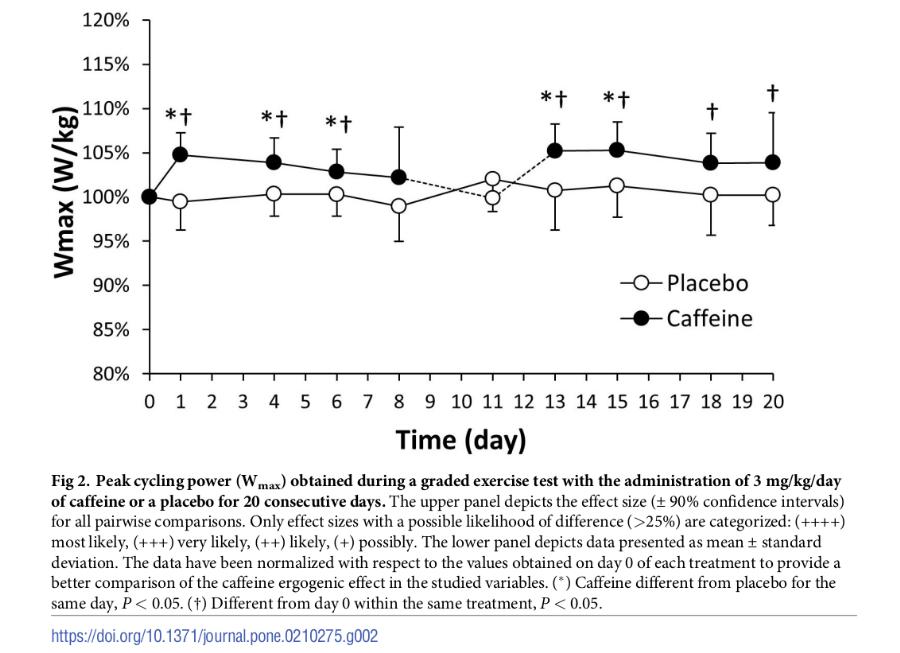

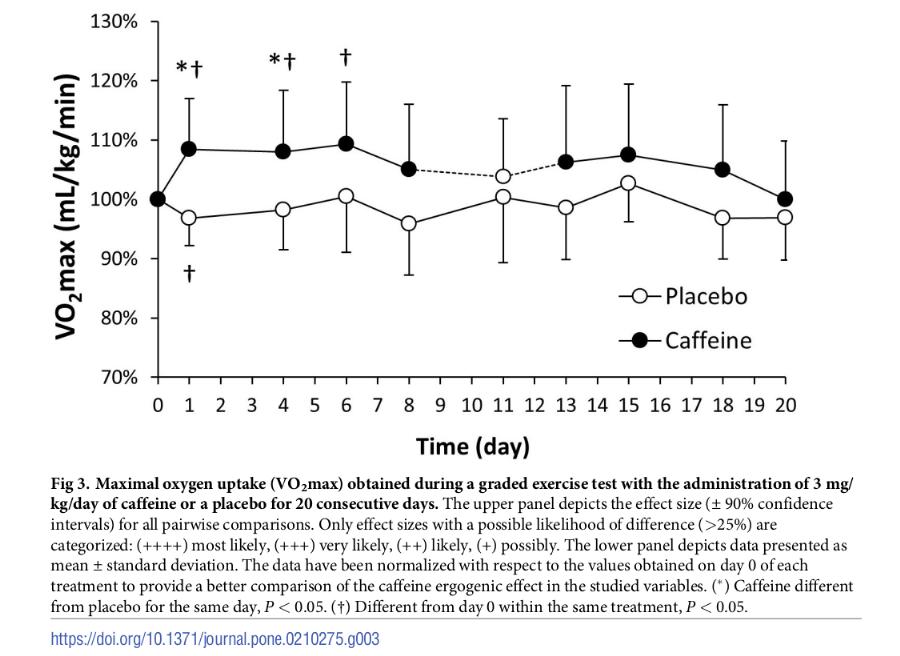

Lara et al 2019 also set out to examine whether the ergogenic effects of daily caffeine diminished over time. Eleven active (>4 days of training per week; > 45 min per day) participants took part in this cross-over, double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment. In one treatment, they ingested 3 mg/kg/day of caffeine for 20 consecutive days while in another they ingested a placebo for 20 days.

For the month prior to the experiment, participants were instructed to refrain from all sources of dietary caffeine and to maintain their regular training routines.

Two days before each crossover phase, and three times per week within each phase, participants performed the same exercise protocol composed of a maximal graded exercise test on a cycle ergometer to volitional fatigue, followed by 7 minutes of active recovery, then an all-out 15 s sprint. With the exception of the initial and day 11 tests, the exercise session always started 45 minutes after ingestion of the assigned capsule.

In comparison to placebo, ingestion of caffeine increased peak cycling power in the graded exercise test by ~4.0% for the first 15 days, but then this ergogenic effect lessened. Peak power was still higher than placebo at day 20, but the difference was no longer statistically significant. However, compared to day 0 of the caffeine phase, daily caffeine intake increased peak power for the entire duration of the caffeine phase.

VO2max was higher to a statistically significant degree on days 1 and 4 when compared to placebo, with the difference diminishing by day 20. Compared to day 0 of the caffeine phase, daily caffeine intake increased peak power on days 1, 4 and 6.

During the day 11 tests, performed without pre-exercise caffeine, there were no differences between treatments.

As for the 15-second sprint, caffeine also increased peak cycling power during on days 1, 4, 15, and 18 by ~4.9%. compared to day 0 of the caffeine phase, daily caffeine intake increased peak power during the sprint for the entire duration of the caffeine phase. The effect size of caffeine intake on peak power was large on days 1 and 4 and was reduced to moderate/small afterwards.

Mean cycling power during the sprint only increased with caffeine on day 1 of ingestion with respect to placebo, and on days 1, 15 and 18 with respect to day 0 of the caffeine protocol. The effect size of caffeine intake on mean sprint power was moderate on days 1 and 4 and decreased to small afterwards.

HIIT Performance

Before I close off the discussion, let’s take a quick look at the effects of caffeine on high intensity interval/intermittent training (HIIT). There are no long-term studies available, only acute experiments.

HIIT sessions typically involve a pre-specified number of sprints performed for a given time or distance. Improvement, therefore, is typically measured by researchers in terms of mean and peak power output during the sprints.

In a 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis, Lopes-Silva et al found the research was mixed, but overall, caffeine ingestion did not improve total work done, best sprint or last sprint performance when compared with placebo.

Conclusion

I’d love to be able to make bold, exciting claims about caffeine. We all love certainty, and we all want something that will give us a clear boost in the gym.

When it comes to caffeine and weight training, neither I nor the science can offer you any certainty. Caffeine in doses between 2 to 6 mg/kg body weight 60 minutes prior to hitting the iron may improve your 1RM or your muscular endurance. If you’re lucky, it might improve both.

There is a pattern of any beneficial effect often being largely confined to the first exercise in a testing session.

While caffeine habituation has long been discussed as a potential confounder, there is no discernible relationship evident between habitual caffeine intake and testing performance. Keep in mind that studies examining the acute effects of caffeine on physical performance almost always stipulate that subjects abstain from caffeine for 12 to 48 hours prior to testing sessions.

An evolving area of research is the effect of genetics on responsiveness to caffeine. CYP1A2 and ADORA2A are currently the most researched genes with regards to the ergogenic effects of caffeine.

Wang et al recently performed a meta-analysis of trials reporting both CYP1A2 genotypes and exercise performance. They found acute caffeine intake improves cycling time trial performance only in individuals with the A allele of CYP1A2. Wingate sprint and counter-movement jump performance did not change after caffeine supplementation, irrespective of genotype.

Given that this is an evolving field of research and that genetic testing for caffeine-responsive gene alleles is beyond the reach of most ordinary folks, the best I can suggest is self-experimentation.

If you wish to use caffeine to enhance performance in competitive sports, experiment with different dosages in your training; don’t leave it to the day of a big event to discover that 6 mg/kg of caffeine gives you gastrointestinal distress and a need to constantly stop and pee.

As for using caffeine on a longer-term basis, there is a paucity of research. With a sole exception, the handful of studies performed so far show little to no effect of caffeine ingestion on longer-term training outcomes. At this stage, caffeine’s benefits appear largely confined to acute boosts in performance. To add to the complexity, Beaumont et al 2016 and Lara et al 2019 suggest even those acute effects diminish over 3-4 week periods in caffeine-naive subjects. It’s hard to make inferences from a mere two studies, but it may be that low or modest habitual pre-exercise caffeine consumption combined with occasional high pre-exercise doses may be the optimal long-term option.

Personally, I have a strong cup of coffee upon rising, and another prior to gym workouts or bike rides, assuming they take place no later than mid-afternoon. On rare occasion, when I’m hellbent on setting a PR on a bike ride, I’ll pop a single NoDoz with my pre-ride coffee.

The very act of drinking coffee gives me pleasure, and I tend to reliably feel the mild stimulatory effects of caffeine, or what’s known as the “caffeine buzz”. An impending workout allows me an additional guilt-free cup of caffeine for the day. In combination with my workout structure, that alone is pretty much guaranteed to put me in the right frame of mind for my training session. So for me personally, caffeine is more of a mood enhancer that helps keep my training enjoyable. I don’t, however, even begin to kid myself that it is a miracle drug with steroid-like effects.

Update July 28, 2025: Beaumont et al 2016 and Lara et al 2019 added to the section discussing longer-term trials; both examined whether the performance benefits of caffeine on stationary cycling diminished with daily use.

Leave a Reply