Finally, researchers do a study comparing strict versus 'cheating' reps.

If you love arguing, but are running out of adversaries, then you really need to join the online bodybuilding community. Those bros never run out of kindling to fuel heated arguments. They argue about everything: The number of sets one should do, high versus low reps, training frequency, training to failure, machines versus free weights, full versus partial reps, front versus back squats, and whether Arnold Schwarzenegger should’ve won the 1980 Olympia (that one’s easy: He shouldn’t have).

Believe it or not, a perennial bone of contention among these folks is the use of strict versus ‘cheat’ form.

Strict form involves performing an exercise with textbook-style technique, using little-to-no external momentum. Cheat reps, in contrast, involve using extra momentum emanating from muscles not directly involved in the movement.

For example, strict performance of the standing biceps curl would involve maintaining an upright posture, with the only notable movement being that of the forearms, as they engage in flexion and extension.

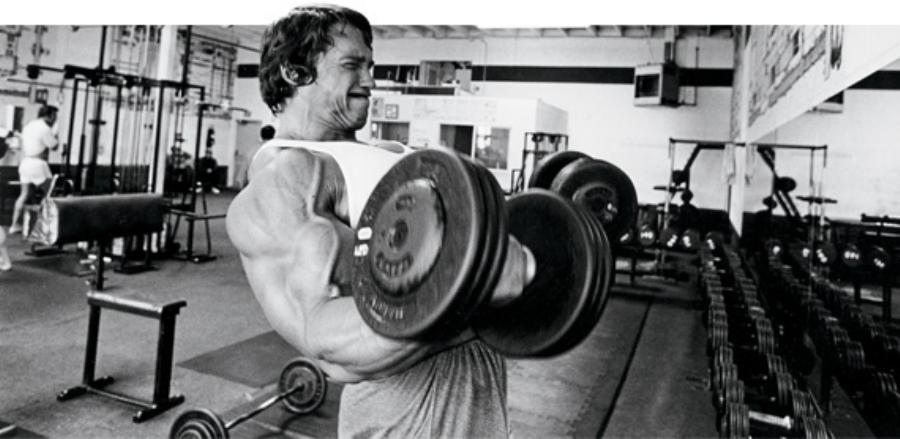

In contrast, ‘cheating’ on the biceps curl would involve leaning forward at the start of the movement, then reflexively leaning back in order to swing the weight up. As the set progresses and the reps become increasingly difficult, further cheating would occur when the weight reaches the mid-way sticking point. To get the weight past this sticking point, our intrepid bro would lean backwards like Schwarzenegger is doing in the picture above.

This significantly changes the dynamics of the movement. There is now a notable degree of flexion and extension occurring in the lower back and hip areas. There is an old adage stating such technique turns a good biceps exercise into a poor lower back exercise.

There are two main reasons people ‘cheat’ in the gym. One is to use heavier weight. The other is to continue a set past the normal point of failure; when another rep using strict form is not possible, some folks will loosen up their form in order to squeeze out another rep or three.

Most reputable trainers insist optimal exercise technique is paramount, both for injury prevention and to ensure the exercise recruits the intended target muscles.

Fans of cheating, however, insist that the extra load allowed by loosening up one’s form paves the way for extra gains in strength and hypertrophy.

So who’s right?

The content below was originally paywalled.

The Lat Pulldown versus Form Breakdown

You see it all the time at your local gym: Matty Mustang, trying to impress his mates Kenny Camaro and Sammy Supra, and the nearby gaggle of semi-naked female ‘influencer’ types, places the pin at the bottom of the weight stack, grabs the lat pulldown bar, then begins heaving and hoeing like he’s trying to row a boat up the side of the Eureka Tower. To let everyone know how hardcore he is, Matty grunts and screams like he’s being violated with a hot iron, while Kenny and Sammy yell, “c’mon bro, you got this!! All yours!! Easy!!!”

Meanwhile, at the neighboring weight station, a quiet but determined Massimo Sensible grabs the lat pulldown bar, leans back slightly, then draws the bar into his upper chest with a minimum of back sway. His form is rhythmic, almost poetic. With each passing rep, his V-shaped back seems to flare wider and wider. Even the scantily-clad influencers momentarily forget the most important thing in their lives - their camera tripods - and look on in awe.

So who’s on the right track here: Matty or Massimo?

Snyder and Leech recruited eight women with little or no strength training experience and had them perform lat pulldowns with only basic instruction, performing 2 sets of 3 repetitions at 30% of their 1 rep max.

After a brief rest, subjects then performed the same 2 sets of 3 repetitions following verbal technique instruction on how to emphasize the latissimus while de-emphasizing the biceps. An NSCA-certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist instructed the women with emphasis on 3 specific elements:

1. Palpating the latissimus dorsi;

2. Informing the subject this muscle should be the targeted muscle for the exercise, and;

2. Explaining to the subject to pull with their back, instead of with their arms, by pulling the shoulder blades back and inwards, and concentrating on the tension in the back musculature.

A significant increase was seen in EMG activity in the latimissimus dorsi from pre-instruction to post-instruction. No significant differences were observed between pre- and post-instruction muscle activity in the biceps brachii or teres major.

The results show that even untrained individuals can voluntarily increase the activity of a specified muscle group during a multi-joint resistance exercise.

They also suggest that, contrary to popular gym wisdom, the increase does not represent ‘‘isolation’’ of the muscle group through voluntary reduction of activity in assisting muscles.

The results indicate that, if you’re after an impressive set of V-shaped lats, you should forget about trying to impress others with prodigious lat pulldown poundages and instead focusing on developing optimal form.

To be sure, this wasn’t a strict vs cheat comparison per se. It examined the immediate effect of teaching newcomers how to perform an exercise properly, to focus on deliberately trying to increase the involvement of the target muscle group rather than mindlessly lift the weight up and down.

This study had other limitations. The subjects were inexperienced weight trainers, and the load used in the study was very light. Few serious lifters use loads of 30%RM on their work sets, even when using picture perfect form.

Most importantly, it was an acute study looking at how changes in technique impacted EMG-detected patterns of muscle activation. It tells us nothing about the actual strength, hypertrophy and injury ramifications of optimal versus suboptimal form over the longer-term.

In a 2012 paper, Arandjelović ‘investigated’ the effect of cheating on the shoulder lateral raise exercise. He concluded the use of moderate momentum at the beginning of each repetition in a set facilitated the use of heavier loads and a better overload of target muscles.

In contrast, excessive use of momentum resulted in the lowering of the loading imposed on the target muscles and decreased total hypertrophy stimulus.

However, these conclusions were arrived at by mathematical modelling. Again, there was no attempt to examine the actual hypertrophy effects of strict versus cheat reps on real live humans over a given period of time.

Finally, a Long Term CHEAT vs STRICT Study

The International Journal of Exercise Science recently published a study by a group of researchers, some of whom will be familiar to regular consumers of online strength content (Jeff Nippard, Milo Wolf, Brad Schoenfeld).

They recruited 30 young male and female volunteers from a university population, 25 of whom completed the eight-week training intervention. The subjects were untrained (defined as not having performed resistance exercise for their upper body in the past year).

To compare the effects of strict versus cheat training, the researchers opted for a within-subject study design, meaning the subjects served as their own controls, performing both strict and cheat reps with opposing limbs.

Here’s how that looked:

The exercises performed during the study were the standing dumbell biceps curl and the triceps cable pushdown.

For every subject, one limb was randomly allocated to perform the curls and pushdowns using strict form (STRICT), and the other using external momentum (CHEAT).

Participants completed four sets of each exercise with 8-12 repetitions until momentary muscular failure, twice a week for eight weeks.

For the STRICT biceps curls, participants were instructed to maintain a stationary body position and avoid swinging the torso, shrugging the shoulders, hyperextending the neck, extending the knees, or rising on the toes to assist in the concentric action.

For the STRICT triceps pushdown, participants maintained an upright torso, and endeavored to keep their upper arms by their sides to ensure elbow extension/flexion was the only movement occurring during the exercise.

For the CHEAT condition, participants began the biceps curl movement by swinging the weight from full extension at the bottom position to full elbow flexion at the top of the movement. They were verbally encouraged to utilize external momentum to lift the weight as often as possible until they reached failure.

For the CHEAT triceps extensions, participants were instructed to use external momentum throughout the set until they could not fully extend the elbow. This included allowing the elbows to flare during each repetition, employing leg drive by bending the knees to assist in the downward motion, and leaning forward to facilitate the completion of a full repetition.

The participants were advised to maintain their customary nutritional regimen during the study.

Before and after the intervention, muscle thickness measurements of the biceps and triceps were taken at two locations each on the upper am via ultrasound.

A three-dimensional optical scanner was also used to assess changes in upper arm girth.

So what happened?

When measured in kg, a higher weekly volume was observed in the CHEAT condition, due to the increased load allowed by the use of momentum.

However, after eight weeks, there were no differences in outcomes between groups.

Using external momentum had no discernible effect on muscle thickness or upper arm circumference compared to performing the same exercises with strict technique.

No injuries were reported during the study, but the researchers noted “the 8-week interventional period and limited number of participants may have been insufficient to adequately assess the topic. Although speculative, continually subjecting soft tissues to excessive external momentum could be deleterious to these structures.

Factors such as the amount of external momentum used during exercise performance and the specific body segments involved (e.g., spine, hips, etc.) may play a role in the associated risk of the strategy. Thus, trainees should take into account the potential increased injury risk from a cost-benefit standpoint when deciding how to perform a given exercise.”

What It All Means

A sole study involving untrained subjects is hardly the final word on a topic. But as the first study in which researchers bothered to compare the hypertrophy effects of performing exercises strictly versus using external momentum, it’s a helpful start.

The results suggest that, at least for single-joint exercises like biceps curls and triceps extensions, there is no benefit to be gained from ‘cheating’ on your form.

I’m a big believer in impressing upon beginners the importance of good technique. I fall firmly into the camp, alongside folks like Mark Rippetoe, that holds newcomers to the weight room should be drilled thoroughly on optimal technique, because this is the foundation period where the adoption of good technique will stand them in good steed for years to come.

The study above did not look at the effect of extending a set by loosening up one’s form after reaching what a lot of folks refer to as ‘technical failure’ - the inability to complete another rep in strict form. Using cheat reps in this manner does not involve using heavier weights, but rather continuing to use the same weight while extending a set. While seemingly safer due to the avoidance of extra load, there is still a potential risk if the cheating reps involve adopting anatomically incorrect positions.

Examples would be rounding of the lumbar spine on squats or deadlifts, hyper-extending the lumbar spine during biceps curls or overhead presses, or flaring the elbows outwards on the bench press rather than keeping the upper arms at a ~45° angle to the torso.

Some commonsense is in order. Descending rapidly and bouncing at the bottom of heavy squats is not a great way to promote knee heath. Likewise, bouncing the bar off your chest during a bench press is poor form, period.

However, proper execution of some exercises is actually facilitated by a little momentum applied at just the right time. Bent over rows and one arm dumbell rows are examples that immediately come to mind.

One of my favorite trap exercises involves performing only the shrug portion of a clean. To the uninitiated, it may look like I’m ‘cheating’ on shrugs in order to lift heavier weights. What I’m really doing is performing a key portion of an Olympic lift, in a deliberate fashion through a pre-specified range of motion.

There’s nothing wrong with an ever so slight amount of backward lean to guide the weight through the sticking point on your last rep of biceps curls. Leaning back in a manner that resembles the start of a limbo dance, however, is inviting lower back injury.

At this stage of the game, there is no compelling reason to sacrifice form for weight. While placing extra strain on your joints and lower back, there is as yet no clinical evidence cheating on your form will increase size and strength gains.

Leave a Reply