Getting buff doesn't have to be an impossible dream ...

Not everyone wants to lose weight. With all the historically recent talk of an 'obesity epidemic', it's easy to forget there are people who need or want to gain weight. Whether it's due to genetics or undernourishment, some folks are underweight. Others might be 'normal' weight, but want to gain muscle mass for aesthetic, self-defense or sports purposes.

If that's you, then pay close attention, because this two-part article will help clear the air on how many calories and how much protein you need to gain muscular body weight.

The content below was originally paywalled.

Food: The Forgotten Anabolic

The bodybuilding world is obsessed with supplements and workout routines. But all the pre-workout boosters and tricky superset combos in the world won't change the irrefutable fact that to gain muscular body weight you need to consume a caloric excess.

Gaining weight is pretty much the weight loss process in reverse.

To lose weight, you need to eat less calories than what you expend.

To gain weight, you need to eat more calories than what you expend.

When 'cutting', you want the lost weight to be comprised mostly of fat, not muscle. Therefore, to preserve precious muscle, you should perform resistance (weight) training when shedding fat.

Unless you're auditioning for the role of Moby-Dick, when 'bulking' you'll want the extra weight you gain to be comprised of muscle, not chub.

Sounds simple so far, but it seems life's main job is to make things harder than we'd like them to be.

The first reality check is that, when bulking, you should expect to gain some fat. Gaining weight is like a tightrope act, where you strive to eat enough calories to induce muscular weight gain, but not so much that you start growing extra chins. Six packs belong in the midsection, remember.

The next reality check is that, while eating more sounds easy, it often isn't. There's a little thing known as satiety that tells you to stop eating, and if you don't seem to be getting the message, the body will start making you feel uncomfortable. A big sticking point for many folks trying to gain weight is that the necessary calorie surplus seems to extend beyond the bounds of their appetite.

We'll talk about practical ways to avert this appetite limitation with food and supplements in Part 2, but first, it's time to get our geek on and delve into the science of getting más grande.

What does the clinical research say about intentionally eating a caloric excess for the purposes of getting jacked?

Let's take a look.

The Clinical Trials

Studies involving intentional weight gain, or "overfeeding" experiments, have mostly featured sedentary, non-training individuals. Only a small portion involved subjects who lifted weights.

The studies with sedentary subjects show that, when deliberately overfed, up to half of the weight gain is comprised of lean mass. The bad news is that at least half and often more will be comprised of adipose tissue.

When you throw training into the mix, however, the picture changes. The training studies are what we're going to discuss today, so let's kick things off with a paper from the era of roller disco, tube socks, Star Wars and going outside without sunscreen.

In 1975, Consolazio et al from the Letterman Army Institute of Research, San Francisco, published a paper describing the results of high caloric diets featuring high or low protein intakes combined with heavy physical training.

Eight healthy young men in their early 20s were divided into two groups: A low-protein group receiving 1.39 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, or a high protein group receiving 2.76 g protein/kg body weight.

During the first ten days of the 40-day experimental phase, the men ate 3,400-3,600 calories daily. This was then increased to 3,700 calories daily during days 11-40. This equates to around 51 calories per kg of body weight daily.

The diets were provided in liquid form, with casein constituting the protein source.

Over the entire 40-day experimental phase, the low protein group averaged 101 grams protein, 93 g fat, 553 g carbohydrate and 3,452 calories daily.

The high protein group averaged 197 g protein, 108 g fat, 442 g carbs and 3,532 calories daily.

During the 40 day experiment the subjects engaged in a "vigorous physical conditioning program" that included treadmill walking, stationary cycling, calesthenics, isometric exercises "and other sporting activities."

So these weren't your average gymgoers training 2-4 times per week, alternating sets of biceps curls with taking selfies for Instagram. They were what I assume to be military recruits undergoing a boot camp-style regimen. While there is no mention of lifting weights, isometrics is a form of resistance exercise that involves exerting force against an immovable object. Calisthenics is the pre-1980s term for a variety of movements we would now refer to as "bodyweight exercise" and "dynamic stretching".

Anyways, after 40 days the low-protein group lost an average 1.09 kg of bodyfat, while the high-protein group lost 2.21 kg of chub.

The low-protein group gained 1.21 kg of lean mass, while the high-protein group gained 3.28 kg of lean mass.

Based on the lean/fat figures provided in the paper, the low- and high-protein groups gained 0.12 kg and 2.07 kg body weight, respectively.

Lean mass gains are often assumed to be muscle gains, but can also be comprised of increases in organ weight. No girth measurements were cited in the paper, and being the 1970s there was no MRI imaging performed to assess changes in muscle thickness.

Nonetheless, the study showed that a hefty caloric intake of up to 3,700 calories daily by highly active young men weighing in the vicinity of 71 kg for 40 days produced favourable changes in body composition, with the most significant changes occurring in those consuming a protein intake almost 3.5 times the pathetically low RDA of 0.8 g per kg daily.

Ohannesian et al from Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia performed an overfeeding experiment in seven twenty-somethings (6 males, 1 female). All the subjects were physically active folks whose exercise regimen included hitting the gym 2-3 times weekly for 45-60 minutes at a time, engaging in aerobic exercises and weight lifting.

The main goal of the researchers was, not to get the subjects jacked, but to observe changes in markers of glycemic control and serum leptin. Previous overfeeding studies in sedentary folks resulted in hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance and increased serum leptin, so the researchers wanted to see if the same occurred when physically active subjects were overfed.

At the start of the study, the subjects' average BMI and body fat percentage were 21.5 and 17.5%, respectively. All were healthy and had no first degree relatives with type 2 diabetes.

There was no control group or comparison group in this study. All subjects volunteered to increase their daily caloric intake for 4-6 weeks by consuming 4-6 cans of Sustacal Plus daily, with the goal of increasing their body weight by 10%. Sustacal Plus contained 50% carbohydrates, 35% fat, 15% protein.

Based on figures provided in the paper, this would have supplied an average caloric surplus of 1,442 - 1,669 calories per day.

The weight-gain phase was followed by an additional two-week phase in which the subjects maintained the weight they had just gained.

The subjects were asked to refrain from alcohol and instructed to continue their usual exercise routines throughout the study. Apart from stating the subjects trained 2-3 times a week for 45-60 minutes, no further details are provided about their weight training routines.

After the final 2-week maintenance phase, the subjects had not quite achieved a 10% weight increase, but gained an average 4.7 kg in body weight (from 64.1 kg to 68.8 kg). Their BMI had risen from 21.5 to 23.4, and their bodyfat increased from 17.4% to 21%.

Again, using the figures supplied by the researchers, this indicates an average lean mass gain of only 1.32 kg. In light of the overall body weight gain of 4.7 kg, it's clear this will not be remembered as history's most successful bulking phase.

The good news is that, unlike what is seen in overfed sedentary subjects, there was little change in fasting glucose or insulin, and insulin sensitivity actually improved in all but one subject despite the weight gain. Serum leptin increased, as it typically does when one gains bodyfat.

The authors wrote that the lack of any negative glycemic outcomes was "good news for healthy, lean, young people who periodically overindulge in food consumption (for example, in the holiday season), but, continue to exercise, as the temporary weight gains in such a setting in the majority of them appear to be metabolically inconsequential."

Even though this is an article about weight gain, I've included that passage because many people who eat to maintain or lose weight have a habit of losing the plot and derailing like a globalist-targeted freight train after eating a 'bad' meal or having a brief binge. Instead of accepting they're human and getting right back on track at the next meal, they embrace the philosophy of "if you're going to have an accident, make it a big one!" They spiral into a protracted binge, as if the answer to a brief slip-up is extended debauchery.

Folks, a single 'unapproved' meal won't wreck your progress nor your health. Just vow to get it together starting with the next meal, or at least the next day, and continue on like The Little Engine that Could, gathering momentum with every mouthful of good food.

"I think I can. I think I can. I know I can. Hell yeah, you bet your mRNA-adulterated ass I can!"

Or something like that.

The next study I was able to retrieve examining the effect of a caloric surplus combined with resistance training was conducted by Rozenek al from California State University at Long Beach.

They took 73 healthy males between 18-35 (mean age 23.3 years) who were mildly active and beginning weight trainers, and randomized them to one of three groups:

Group 1 subjects, in addition to their normal diet, consumed a supplement providing an extra 2,010 calories, 106 g protein and 356 g of carbohydrate daily.

Group 2 subjects consumed a supplement supplying the same amount of extra calories but comprised entirely of carbohydrate.

Group 3 was comprised of control subjects, who consumed no calorie-containing supplement, just their regular diet.

All subjects were placed on a four-day-per-week resistance training routine for 8 weeks. Training sessions lasted 60-90 minutes, including a 5-10 minute warm up. The routine included 1-2 exercises per bodypart, performed for 4 sets at 70% RM.

Based on the caloric content of the supplements and 3-day food diaries kept by the subjects during weeks 1, 4 and 8, average daily caloric intakes were 4,348 and 4,339 per day in Groups 1 and 2, respectively.

Based on each group's mean starting body weight, this equates to 56.7 calories/kg and 57 cals/kg daily for Groups 1 and 2, respectively.

The Group 3 controls, in contrast, consumed an average 2,597 calories per day (33.4 cals/kg).

Daily protein intakes for Groups 1, 2 and 3 averaged 3.0 g, 1.7 g and 1.4 g per kg of body weight, respectively, during the eight weeks.

Those who've fallen for the low-carb propaganda would assume the high-carb subjects fattened like balloons. Here's what actually happened:

The average body weight gain for Group 1, taking the protein/carb supplement, was 3.1 kg.

The average body weight gain for Group 2, ingesting the 100% carbohydrate supplement, was 3.1 kg.

The control group, meanwhile, registered a statistically non-significant 0.6 kg increase in body weight.

Fat-free mass increased by a statistically significant 2.8 kg, 3.4 kg and 1.4 kg in Groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Body fat percentage and fat mass remained unchanged in Group 1. Marginal but statistically non-significant decreases were observed in Group 2. Group 3, not consuming excess calories, lost 1.3% bodyfat and 0.8 kg of fat mass.

Groups 1 and 2 experienced statistically significant increases in upper arm, forearm, chest and thigh circumferences. The high-carb Group 2 also experienced statistically significant increases in circumference of the buttocks, the all-important sex-siren muscle group that has launched a thousand Instagram careers.

Group 3, in contrast, experienced a statistically significant increase only in chest circumference.

When tested for 1RM on the leg press, bench press and lat pulldown before and after the intervention, the high-protein Group 1 showed the greatest combined increase of (an additional 67.5 kg, compared to 41.6 kg and 43.7 kg in Groups 2 and 3, repsectively). However, the differences between groups were not statistically significant, which could mean one of two things: The greater strength increase in the high-protein subjects was simply a chance occurrence, or was due to the diet but the study was statistically underpowered to register it as significant.

What the study did show was that subjects consuming an even greater caloric excess than those in the small Ohannesian et al study obtained totally different results, with little change in body fat and greater lean mass gains.

I would bet this is due to the different study methods. In the Rozenek study, the researchers ran a tight ship. Anyone who missed a training session was required to make it up on the next rest day, and all subjects completed the required 32 sessions.

In the Ohannesian et al study, the subjects were told to continue their usual training, which allegedly comprised 2-3 weekly gym sessions. These sessions were unsupervised and we don't actually know if the subjects trained with this frequency each week. If they did, we still don't know what exercises they did and how hard they trained. If you've ever observed the average gymgoer, who spends more time on his/her phone than actually training, it's not hard to work out why the supervised Rozenek et al subjects experienced much better results.

If you're going to eat like you mean it, then you'd better train like you mean it. Otherwise, instead of resembling an Adonis, you'll risk looking like Jimmy Moore. You shouldn't need me to tell you that looking like a Greek god is far more desirable than looking like a sexual deviant from South Carolina.

Now put the damn phone down and squat 'til it hurts.

These two papers examined the effect of overfeeding, not mildly active civilians, but elite athletes with a high weekly training volume.

Garthe et al, from the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences and the Norwegian Olympic Sports Centre, Oslo, Norway, recruited forty-seven athletes (17–31 years of age), with 39 athletes completing the 8–12 week weight-gain intervention (most subjects were males, with 2 females in each group).

The final sample included national-level athletes from rowing, soccer, volleyball, taekwondo, skating, ice hockey and kayaking.

The athletes were screened and randomized into one of 2 groups, both of which were ascribed the goal of gaining 0.7% of body weight per week.

One group received nutritional counselling once a week for the duration of the intervention. The counselling included basic nutrition, sports physiology, and possible adjustments in the dietary plan, depending on progress.

The other group received no counselling, but was instructed to eat ad libitum during the intervention period with the goal of gaining 0.7% of their body weight weekly.

After the intervention period, the athletes received 1 nutrition counselling session and 1 exercise counselling session to stabilize their new BM and body composition.

The athletes continued their usual sports-specific training, which averaged 16.7 hours per week. All athletes undertook four resistance-training sessions per week, using a 2-way split routine. Each muscle group was exercised twice a week with two exercises per session, using one multiple joint exercise (e.g. squat) and one isolation exercise (e.g. knee extension). The routine was periodized, with sets-per-exercise increasing from 3 to 5 and reps varying between 6-12 per set.

The mean time spent on the weight gain intervention was ten weeks.

Despite the admonition to strive for a weekly 0.7% body weight gain, subjects in the ad libitum group did not report any increase in caloric intake nor of any macronutrient.

Subjects in the counselling group, in contrast, increased their reported caloric intake from a mean 3,041 to 3,585 daily - a 544 caloric surplus.

Based on their baseline weights, this equates to a daily caloric intake of 50.7 calories/kg and 39.6 cals/kg in the counselled and ad libitum groups, respectively.

Protein intake increased from 1.8 to 2.4 g/kg daily (it remained at 1.7 g/kg in the ad libitum group).

Carbohydrate intake increased from 5.4 to 6.8 g/kg daily, while fat intake remained at 1.4 g/kg daily.

This meant the macro ratio of the counselling group during the weight gain intervention was 20% protein, 25% fat and 55% carbohydrate.

Despite reporting no increase in caloric intake, the ad libitum group gained 1.2 kg of body weight and 1.2 kg of lean body mass, which suggests their dietary records weren't entirely accurate.

The counselling group, being guided by sports nutritionists throughout the intervention, gained 2.7 kg of body mass and 1.7 kg of lean body mass.

The extra 0.5 kg of lean mass gains in the counselling group was attributed to a 0.5 kg gain in lower body lean mass, which did not change in the ad libitum group (both groups experienced a 1.1 kg gain in upper body lean mass).

The counselling group gained 1.1 kg of body fat, compared to 0.2 kg of body fat in the ad libitum group.

Both groups improved their 1RM on the bench press, bench pull and squat to a similar degree.

No athletes in the ad libitum group accomplished their body weight goal during the intervention.

Spillane and Willoughby recruited healthy young males who reported consistently having resistance-trained thrice weekly for at least 1 year. Twenty-one participants (average age 20 years old) completed the study.

In double-blind fashion, participants were assigned an eight-week daily supplementation protocol of either:

a maltodextrose supplement supplying 312 g/day of carbohydrate and 1,248 calories, or;

a protein/carbohydrate supplement comprised of 94 g, 196 g, and 22 g of protein, carbohydrate (from maltodextrose), and fat, respectively. This supplement also supplied 1,248 calories.

For both supplements, the total daily dosage was mixed with water and a half-serving ingested 30 minutes prior to each exercise session, the other half within 30 minutes after the session. On non-training days, the full dosage of supplement was ingested in the morning upon waking.

As for training, the participants engaged in supervised, four-day per week resistance training, split into two upper- and two lower-body workouts per week. Participants performed three sets of 8-10 repetitions with as much weight as they could lift per set (typically 70-80% of 1RM).

At the start of the study, the protein/carb group were reportedly consuming 2,559 calories per day, which increased to 3,816 calories by day 57 thanks to the supplemental calories.

The corresponding figures for the group supplementing carbohydrates only were 2,735 and 3,669 calories.

This equates to a caloric increase of 1,257 and 934 calories in the mixed and carb-only supplement groups, respectively.

Based on their baseline weights, this equated to a daily caloric intake of 45.3 calories/kg and 42.6 cals/kg in the protein/carb and carb-only groups, respectively.

Daily carbohydrate intake at Day 57 had increased to 495 g in the protein/carb group and 597 g in the carb-only supplement group.

As a result of the extra protein, the protein/carb group increased their reported protein intake from 109 grams at the start of the study to 214 grams at day 57.

In contrast, the group ingesting the carb-only supplement decreased their protein intake from 109 grams per day to only 90 grams per day.

Based on their mean starting weights of 86.09 kg and 84.3 kg, this meant the protein/carb and carb-only groups consumed 2.49 g and 1.07 g per kg of protein daily, respectively.

All deluded vegan propaganda aside, the latter figure constitutes an inadequate protein intake for active people, especially those who are looking to gain muscular body weight.

At day 57, total body mass increased by 3.83 kg and 1.42 kg in the protein/carb and carb-only groups, respectively.

Lean body mass increased by 2.28 kg and 0.25 kg, respectively.

If you're wondering how a keto diet would fare for bulking, this study by Spanish researchers will surely be of interest. Researchers from Málaga recruited twenty-four healthy men with more than 2 years of continuous experience in resistance training (mean age 30; height 177 cm; weight 76.7 kg).

The participants were randomly assigned to a ketogenic diet, non-keto diet, or to a control group.

To "guarantee" a calorie surplus, a daily energy intake of around 39 calories/kg was targeted in all subjects. The non-keto group was given a daily protein target of 2 g/kg. Macronutrient distribution for this group was 20% protein, 25% fat and 55% carbohydrate.

The keto diet group was also instructed to consume 2 g/kg/day protein, but only 42 g carbohydrates daily to ensure ketosis. The remaining calories came from fat. Macronutrient distribution for the keto group was around 20% protein, 70% fat, and <10% carbohydrate. Compliance with the keto diet was monitored weekly by measuring urinary ketones with Ketostix.

During the eight-week intervention, both diet groups completed four resistance training sessions per week, with 2 upper-body and 2 lower-body workouts weekly. A total of 8 exercises were performed per session, each for 3 sets of 6-8 reps to failure. All sessions were supervised by a resistance training specialist.

The control group subjects, meanwhile, were asked to maintain their current level of physical activity during the study.

After eight weeks, the keto diet had completely failed for gaining both body weight and lean mass. Even the control subjects scored better on these outcomes.

The non-keto diet gained 0.9 kg body weight and 1.4 kg lean mass, whole losing 0.4 kg fat mass.

The control group, instructed to carry on as usual, gained 0.3 kg body weight, 0.8 kg lean mass, while losing 0.6 kg fat mass.

The keto diet, in contrast, lost 1.4 kg body weight, 0.3 kg lean body mass, and 1.1 kg fat mass.

The fact that the keto group lost weight indicates they not only failed to achieve a caloric excess, but in fact ended up consuming a calorie deficit. The exact opposite of what they were told to do. Low-carb and keto fanatics, having begun consuming unbridled amounts of fatty foods, assume they are "eating more than ever!™". They then conclude any subsequent weight loss is the result of a mythical “metabolic advantage”, a theory with no scientific backing and completely debunked by ward trials dating back to the 1930s.

While it is no doubt true many low-carb newbies are eating more fat-rich foods than ever after beginning their new diet, they seem to suffer severe head trauma-level amnesia when it comes to the poop ton of calories they've deleted by eliminating bread, pasta, rice, all grain products, potatoes, pastries and confectionery, soda drinks, 'sports drinks', fruit juices, etc, etc.

When you lose weight on a low-carb diet, it means one thing and one thing only: You consumed less calories than what you expended. There's only so much fat-rich fare you can eat before having to bolt to the restroom to perform the bentover hurl. The Vargas et al study would indicate that for bulking, keto diets are an inferior choice to mixed diets because they do not lend themselves to the kind of hypercaloric intakes required to gain muscular body weight.

Even if you are able to consume a caloric excess on a keto/low-carb diet, the research indicating potential negative effects on anabolic hormones, cortisol levels and glycogen stores (which I've written about previously) means they still don't make it onto my recommended list.

In this study, eleven Brazilian male IFBB-affiliated amateur bodybuilders (mean 26.8 years, 90.1 kg) were randomly assigned into one of two groups during their competitive off-season:

Group 1 reportedly consumed 67.5 calories/kg/day;

Group 2 reportedly consumed 50.1 calories/kg/day.

Both groups performed resistance training 6 days per week over the 4-week study period. The participants followed a 3-way split routine in which each bodypart was trained twice per week, and all workouts were supervised by physical education instructors.

All exercises were performed for 4 sets with the load increasing and the number of repetitions decreasing simultaneously with each set (the ascending pyramid method). The number of repetitions for each set was 12/10/8/6 repetition maximum, respectively. The number of repetitions per set was higher for wrist and calves (15-20 RM) and abdominals (150 to 300 reps per session).

While other studies have used liquid supplements to supply the caloric excess, this experiment looks to have relied on solid food. Participants were instructed to eat every 3-4 hours, with ok'd foods including rice, bean, potato, manioc, pasta, fruits, vegetables, nuts, oats, juices, meats, eggs, milk, yogurt, and oils.

The mean reported daily caloric intakes for Groups 1 and 2 were 6,088 and 4,501, respectively.

Daily protein intakes for Groups 1 and 2 were 162 g and 185 g, which equates to 1.8 and 2.0 g/kg daily.

Carbohydrate intakes were a mighty 1,170 g and 726 g, respectively. Fat intake in the two groups was 84 g and 95 g, respectively.

At 4 weeks, Group 1 had gained 1.0 kg of muscle mass and their bodyfat rose from 16.2% to 17.4%. Group 2 gained 0.4 kg of muscle mass while bodyfat % remained unchanged.

It should be noted body composition measurement in this study was not what you'd call state of the art. According to the methods section, skeletal muscle mass was determined by a mathematical equation using height, weight, age, gender, and race. Body density and bodyfat % was determined with skinfold calipers.

This study, conducted at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, did not feature a comparison or control group. Instead, all twenty-one subjects who completed the study were instructed to maintain their habitual dietary intake while consuming an additional high-calorie protein/carbohydrate supplement provided by the researchers (Super Mass Gainer™ by Dymatize). Participants were given a half-serving daily, which supplied 26 g protein, 5.5 g fat, 123.5 g carbohydrate and 647.5 calories daily. On training days, the supplement was consumed in the laboratory immediately following the weights session. On non-training days, participants were allowed to consume the supplement at their preferred time.

During the six-week intervention, the subjects trained thrice weekly under supervision. They performed a lower-body workout on Day 1, an upper body workout on Day 2 and a whole body workout on the third training day. The majority of exercise were performed for 2-3 sets in the 8-12 rep range.

At baseline, the subjects reportedly consumed 46.8 calories/kg, which rose to 52.3 cal/kg during the intervention.

Daily pre-and post-intervention protein intakes were 2.3 and 2.2 g/kg, respectively. Fat intake rose slightly from 1.7 to 1.9 g/kg, while carbohydrate intake rose from 5.6 g to 6 g/kg daily. while

Mean body weight rose from 73.8 to 79.6 kg. The researchers don't provide absolute body composition figures, but state the group average suggested all of this gain was fat free mass. The individual results reportedly showed variation, as is typical of these studies, with some gaining fat and some losing fat.

Muscle thickness as determined by ultrasound increased a mean 4.5% for biceps and 7.4% for rectus femoris of the thigh.

Based on the per kg figures provided in the paper, lower body performance improved to a far greater degree than for upper body.

Mean bench press and leg press 1RMs rose from 95.8 kg to 111.4 kg and from 243.5 kg to 334.3 kg, respectively.

To assess muscular endurance, subjects were tested with a weight equating to 70% of their 1RM. At study commencement, the mean rep count on the bench and leg press with this load was 14 and 15.4, respectively. By study's end this had improved to 19 and 34.9, respectively.

The Ad Libitum Protein Studies

The next four studies did not explicitly investigate a caloric excess, but were instead designed to examine the effect of different protein intakes on resistance training athletes. However, all four studies claimed caloric surpluses in the high-protein groups, so I'll provide a quick rundown of each one here.

The first three of these studies were all headed by sports scientist Jose Antonio, from Nova Southeastern University, Florida.

Antonio et al 2014

In their 2014 paper, Antonio and colleagues reported on healthy resistance-trained individuals randomly assigned to one of 2 groups:

A control group, instructed to maintain the same training and dietary habits during the 8 week study;

A high-protein group, instructed to consume 4.4 g of protein per kg body weight daily. Aside from the increased protein, they were also instructed to maintain the same training and dietary habits (e.g. maintain the same fat and carbohydrate intake).

In order to achieve this ungodly protein target, the high-protein subjects consumed commercially available whey and casein protein powders (from MusclePharm® and Adept Nutrition/Europa®).

Forty subjects began the study, 10 dropped out.

The study featured males and females, with a lopsided ratio between groups: There were 9 females and 11 males in the high-protein group, and 2 females and 8 males in the control group.

The participants had reportedly been resistance training regularly for the last 8.9 years and 8.5 hours per week, on average.

If we're to believe the subjects' dietary self-reports, daily caloric intake declined in the control group from 2,295 to 2,042, but increased in the high-protein group from 2,042 to 2,835.

Self-reported daily protein intake in the control group was 1.9 g/kg, compared to 4.4 g/kg in the high-protein group.

Despite the alleged calorie reduction (and greater increase in training volume) claimed by the control group, they gained 0.8 kg body weight, 1.3 kg fat-free mass and 0.3 kg fat mass. Which means the dietary and/or training records weren't accurate.

The high-protein subjects gained 1.7 kg body weight, 1.9 kg fat-free mass, and lost 0.2 kg fat mass.

None of these differences were statistically significant.

Very little information about the subjects' training regimens were provided, except that both increased their training volume, the control group more so. Again, the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Their follow-up study featured forty-eight healthy resistance-trained men and women, randomized to either a 'normal' protein group or high-protein group. According to the dietary records, “normal” during the study was 2.3 g/kg/day, while “high” was 3.4 g/kg/day.

This time, instead of being left to follow their usual training routine, the subjects were instructed to follow a 5-day-per-week resistance training program. The workouts were not supervised; instead, research staff contacted the participants to check compliance.

Seventy-three subjects began the study, but heavy attrition saw 25 subjects dropping out, 22 of whom did not provide a reason.

Pre- and post-intervention self-reported daily caloric intakes were 2,016 and 2,119 versus 2,240 and 2,614 for the normal- and high-protein groups, respectively.

Again, these self-reported figures are highly doubtful. Despite the alleged 374 extra daily calories averaged by the high protein subjects, their weight barely changed (a 0.1 kg loss). The normal protein group, meanwhile, with its 103 calorie increase, experienced a 1.3 kg weight gain.

Fat-free mass increased by 1.5 kg in both groups, while fat mass declined by 0.3 kg and 1.6 kg in the normal- and high-protein groups, respectively.

This time the researchers used a crossover design, in which resistance-trained male subjects underwent two 8-week study periods in random order. During one of these phases, they reportedly ate 2.5 g protein/kg body weight daily; during the other phase, they consumed 3.2 g/kg daily.

As in the first study, each subject followed their own strength and conditioning program during the study.

According to dietary self-reports, the subjects averaged 369 calories extra per day during the higher-protein phase. Despite this, no weight gain occurred in either phase and there were no differences in body composition outcomes.

Campbell et al, from the University of South Florida, recruited twenty-one healthy, young, aspiring female physique athletes, 17 of whom completed the 8-week intervention. In order to qualify for participation into the study, all participants were required to have resistance trained for the previous three months or more and to deadlift 1.5 times their body weight.

After receiving instructions on how to track their food intake using a smartphone app (MyFitness Pal®), participants were matched according to total fat mass and randomized to a high protein group (at least 2.4 grams of protein/kg/day) or a low protein group (instructed to ingest no more than 1.2 grams of protein/kg/day).

Baseline weight and bodyfat % in the two groups was well-matched, averaging 61.2 kg/22.7% and 61.4 kg/21.4% in the high- and low-protein groups, respectively.

No restrictions or guidelines were placed on dietary carbohydrate or fat intake during the study for either group. Participants in the high-protein group consumed 25 grams of whey protein isolate (Dymatize ISO-100) immediately before and another 25 grams immediately after each resistance exercise bout in the presence of research personnel.

Participants in the low-protein group consumed 5 grams of whey protein isolate (Dymatize ISO-100) immediately before and another 5 grams immediately after each bout, also under supervision.

Each participant had access to their individual nutrition coach throughout the study duration to answer any nutrition questions related to selection of food choices and adhering to their assigned diet.

The resistance-training program consisted of two upper-body and two lower-body sessions per week, comprising 6 and 5 exercises, respectively. The set and repetition ranges varied throughout the program, including five sets of 3-5 repetitions, 4 sets of 9-11 repetitions, and 3 sets of 14-16 repetitions. Participants reportedly self-selected a weight that would allow them to complete the required number of reps while stopping one rep short of failure. During weeks 4 and 8, the subjects only performed 2 workouts per week, as a taper.

Unlike most of the other studies, in which subjects were either told to carry on their usual training or not do any additional cardiovascular conditioning, the subjects in this study were also assigned high intensity interval training (HIIT). This consisted of a series of 30-second, maximal intensity sprints that progressively increased in number throughout the study (from 4 sets during the first 2 weeks to 7 sets in the final two weeks). Participants were allowed to choose their preferred mode of HIIT exercise (treadmill, outdoor sprinting, cycle ergometer, rowing machine, etc) and were instructed to rest two minutes between each set. While we know the subjects were to hit the weights four times weekly, it does not explicitly state in the paper how many HIIT workouts were scheduled for each week.

During the intervention, the high-protein subjects increased their reported daily caloric intake from 1,588 to 1,839, a small 251 calorie increase.

The low-protein subjects reportedly decreased their caloric intake from 1,708 to 1,416.

This equates to 30 calories/kg body mass in the high-protein subjects, and 24 cals/kg in the low-protein group. Even the high-protein group's mean calorie intake was quite low compared to what we've seen in other calorie surplus studies.

At eight weeks, body weight increased by 1.0 kg in the high-protein group, and dropped by 0.2 kg in the low-protein group.

Fat-free mass increased +2.1 kg and +0.6 kg in the high-protein and low-protein groups, respectively.

Fat mass decreased by 1.1 kg and 0.8 kg the high-protein and low-protein groups, respectively.

Improvements in squat and deadlift 1RM were similar between groups.

Making Sense Of It All

The next step is to seek out common threads in the above studies and arrive at some general recommendations for those wanting to gain mass.

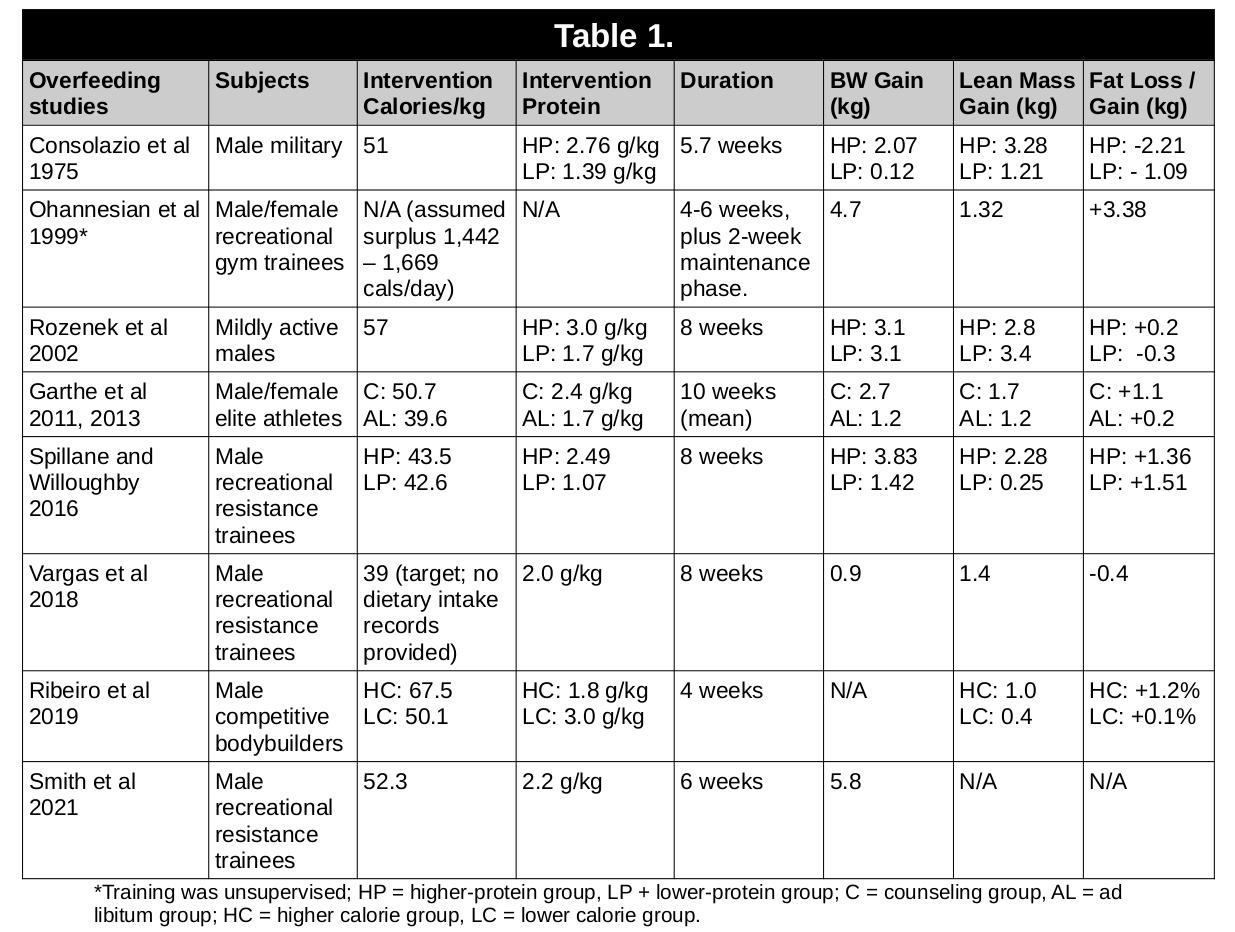

I've summarized the stats for the groups experiencing weight gain in the table below:

Because we're seeking optimal targets for weight and lean mass gain, I've left out the data for control groups and intervention groups that did not achieve weight/lean mass gains, such as the keto diet group from the Vargas et al study.

You’ll also note I've omitted the protein/ad libitum studies by Antonio et al and Campbell et al. They were not specifically designed to induce a caloric excess, although I might still have included them had the data been tenable. However, the Antonio et al studies reported weight increases in people who allegedly cut their caloric intake and increased their training volume, and reported no body weight changes in people allegedly consuming a caloric excess. These results simply don't add up and indicate there were major issues with dietary reporting in those studies.

I would have loved to include the Campbell et al study, as it was the only all-female study. But again, the dietary data is untenable. The cited caloric intakes were very low for women resistance training 4 times per week and performing HIIT exercise. If we're to believe the self-reported dietary data, the women in the high-protein group gained weight and lean mass consuming only 1,839 calories per day, while the body weight of the low-protein subjects barely changed on a measly 1,416 calories per day.

No way, ese.

Using a Cosmed device, the researchers estimated baseline resting metabolic rate (RMR) energy expenditures of 1,466 and 1,451 calories in the high- and low-protein groups, respectively.

RMR, however, only measures your energy expenditure when you are sitting still. Unless you spend 24 hours a day in a relaxed, reclined position, RMR fails to take in the additional energy expenditure from your daily non-exercise and exercise activity.

At the start of the study, the high-protein subjects averaged 61.2 kg and 22.7% bodyfat, similar to the low-protein group which averaged 61.4 g and 21.7% bodyfat.

Using the Katch-McArdle RMR formula that I included in The Fat Loss Bible, we get RMRs of 1,392 and 1,409 calories for the high- and low-protein groups, respectively - not too far off what the Cosmed device showed. So the RMR figures cited by the researchers are legit.

However, when we take the Cosmed-derived RMRs and apply the Harris-Benedict multiplier of RMR x 1.55 for individuals who are "Moderately active (moderate exercise/sports 3-5 days/week)", we end up with TDEEs of 2,272 and 2,249 calories/day for the high- and low-protein groups, respectively.

Remember, those new figures are the daily caloric targets one would need to meet to maintain weight. If the high-protein group truly consumed a 251-calorie surplus over the maintenance requirements, they would have been consuming 2,523 calories per day - around 700 more than what the dietary self-reports claimed.

Of course, if the overall caloric intakes were underreported, then the calorie surplus was probably underreported too.

Bottom line is that I simply cannot place any stock on the caloric figures in the Antonio and Campbell studies.

That leaves the intentional overfeeding studies, most of which cited daily caloric intakes of 50-57 calories per kg of body weight and daily protein intakes between 2.2 and 2.76 g/kg.

The Ribeiro et al study with competitive bodybuilders went as high as 67.5 calories/kg and 3.0 g/kg, yet lean mass gains in the high-calorie group after 8 weeks amounted to only 1 kg, which is quite low. This again calls the accuracy of the dietary self-reports into doubt.

It's also worth noting the participants in the Ribeiro et al study had the highest-volume training routine of all the above studies, with participants training six days a week on a routine using three exercises for major muscle groups and 2 exercises even for small muscle groups like forearms and calves.

The highest body weight gain and the highest lean mass gains (if we're to accept the researchers' claim that most of the gain was fat-free mass) occurred in the Smith et al study which used a 3-day per week routine. Upper body and low body were alternately trained in two of those weekly workouts, while the third training day was a whole body session.

This would tend to support my contention that, when it comes to resistance training, not only is more not necessarily better, it's often worse.

Hitting the weights six days a week might be fine for young, state-sponsored athletes who don't need to work a regular job, get free daily massages, can take naps after training, and whose coaches inject them with anabolic, uh, I mean, 'vitamins'. It's also worth remembering when you read stories of elite Eastern Bloc athletes training multiple times daily, six days per week, that these athletes are the survivors of a Darwinian "burn and churn" system where promising athletes are hammered with high volume training and only those that endure and survive this training progress to the elite level.

Those who struggle to consume a caloric excess also need to keep in mind that resistance training consumes extra calories, and that hitting the weights daily will simply create an extra calorie burn that will of course necessitate an even greater caloric intake. You're trying to get buff, not emulate a hamster on a spinning wheel.

After reviewing the trials comparing one-set-to-failure training with multiple set training (as a paid subscriber, you can read my review here), it became apparent to me there is essentially no quality peer-reviewed evidence underpinning the alleged superiority of the latter. My advice would be to do what Dorian Yates did and design your mass program to squeeze the most results from the least amount of training.

So again, my recommendation for a productive bulk would be a starting calorie target of at least 50 calories/kg body weight, a minimum of 2.2 g/kg dietary protein, and a resistance training frequency of 3-4 days per week.

These figures are not only supported by the above studies but by decades of empirical observation. Given that a pound equals 2.2 kg, the 2.2 g/kg protein figure corresponds neatly to the 1-gram-protein-per-pound-body weight that has been a commonly-cited rule of thumb in bodybuilding circles for as long as I can remember.

Having said that, it behooves me to point out the studies above all suffer a key limitation:

None were metabolic ward studies, all relied on self-reported dietary intake to ascertain daily calorie and macronutrient intakes.

Long time readers and those who have read my book The Fat Loss Bible will know I'm extremely wary of self-reported dietary intakes in research studies because they tend to be about as accurate as Greta Thunberg's global warming predictions.

One group of high-profile obesity researchers stated outright in a 2015 paper that "self-reports of [energy intake] and [physical activity energy expenditure] are so poor that they are wholly unacceptable for scientific research on EI and PAEE."

Ouch.

Which is why dietary charlatans of all stripes hate ward studies and love free-living studies that rely on self-reporting; these are the only types of studies that can support their nonsensical dietary claims.

In metabolic ward studies, the experimental diets are prepared by researchers and consumed under the watchful eyes of clinical staff. While cheating is still theoretically possible in some cases by especially determined subjects depending on the level of observation and access to outside visitors, it is obviously much more difficult and unlikely to occur.

In free-living studies, the participants are given dietary instructions, then sent back into the big wide world of temptation and broken promises to fend for themselves. The researchers literally have no control over what subjects actually eat. In an attempt to gauge compliance, researchers ask participants to fill out food diaries or questionnaires. As we saw in the Antonio et al studies, for example, these dietary self-records often defy reality. What these types of studies have shown us of over the last several decades is that humans tend to suck at math and record-keeping. To make matters worse, many free-living studies only require subjects to log their food intake for random 3-day periods during studies that can last months.

Before acting upon the results of a study employing a calorie surplus of, say, 1,500 calories per day, we need to be confident the subjects actually ate that amount of extra calories. If it turns out the subjects only ate a surplus of 750 calories, but recorded a surplus of 1,500 to please the researchers, we might gain much more more bodyfat than we intend.

Conversely, in studies such as those by Garthe et al, where participants reportedly consumed a relatively small calorie surplus yet still experienced weight gain, we have to consider whether underreporting was a factor (judging by the results seen in the control group, this would appear to be the case).

Unfortunately, there are no overfeeding ward studies involving individuals engaged in resistance-training. As research becomes more expensive and increasingly dominated by government and drug company agendas, don't expect this to change anytime soon.

We do, however, already have a number of overfeeding ward studies conducted in sedentary subjects, and it makes for an interesting and informative exercise to review their results - which is what I'll do in Part 2.

The Mandatory “I Ain’t Your Mama, So Think For Yourself and Take Responsibility for Your Own Actions” Disclaimer: All content is provided for information and education purposes only. Individuals wishing to make changes to their dietary, lifestyle, exercise or medication regimens should do so in conjunction with a competent, knowledgeable and empathetic medical professional. Anyone who chooses to apply the information on this substack does so of their own volition and their own risk. The author/s accept no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any harm, real or imagined, from the use or dissemination of information contained on this substack. If these conditions are not agreeable to the reader, he/she is advised to leave this substack immediately.

Leave a Reply