In fact, placebo was better over the long term ...

A recent study pitted a commonly-prescribed opioid against a placebo pill for acute back and neck pain, and …

… the placebo won.

The recently published trial was conducted by researchers at the University of Sydney in Australia. As I've written previously on this site, Australians tend to be staunch believers in using toxic chemicals to deal with life's problems, be they physical or psychological in nature. It's a trait that places Aussies among the world's biggest boozers, sits them alongside North Americans and Kiwis as the world's biggest users of illicit recreational drugs, and positions them as the world's third most avid users of antidepressants.

Little surprise then, that despite a global push to reduce the use of opioids, Australia has seen a significant increase in opioid prescriptions since 2004, accompanied by a significant decrease in the rate of NSAID recommendations by doctors. As the researchers who reported this disturbing trend noted, "GP’s analgesic recommendations for spinal pain have become increasingly divergent from guideline recommendations over time."

Hey, why would you listen to cautious guidelines when drug company sales reps give you lots of free stuff with Pharma logos on it?

Priorities, people, priorities!

The recent trial sought to clarify the efficacy and safety of a "judicious short course" of an opioid analgesic for acute low back pain and neck pain. The researchers had previously analyzed some 14,000 emergency department visits for low back pain between January 2016 to June 2018, and found a whopping 70% of patients received opioids - despite little evidence of their efficacy.

The triple-blinded, placebo-controlled RCT recruited adults presenting to one of 157 primary care or emergency department sites in Sydney with 12 weeks or less of low back and/or neck pain of at least moderate pain severity.

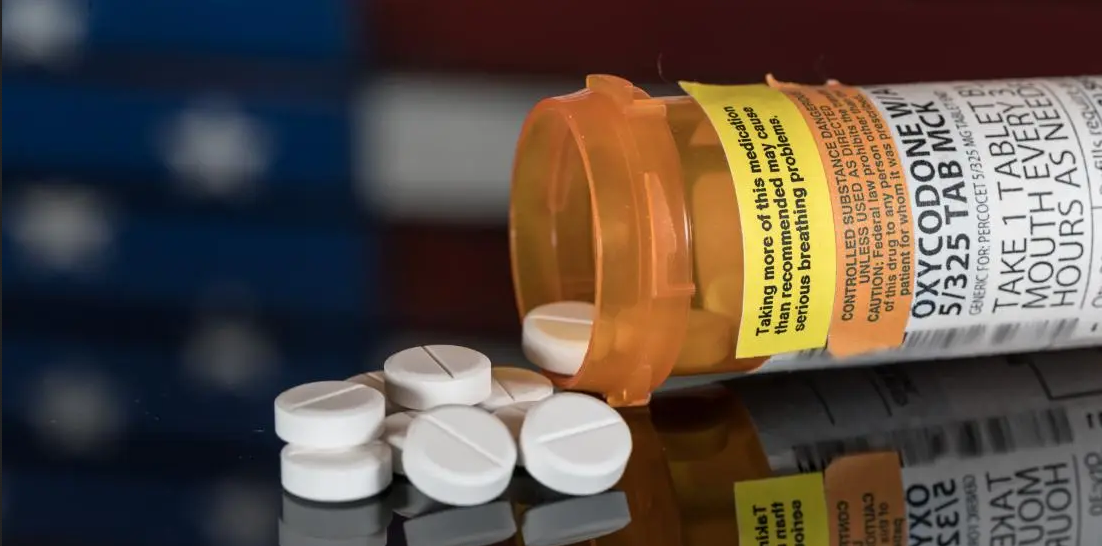

Participants were randomly assigned to guideline-recommended care plus an opioid (oxycodone–naloxone, up to 20 mg oxycodone per day orally) or guideline-recommended care and an identical placebo, for up to 6 weeks.

The primary outcome was pain severity at 6 weeks, measured on the pain severity subscale of the widely-used Brief Pain Inventory. The BPI rapidly assesses the severity of pain and its impact on functioning, with 0 indicating no impact and 10 representing complete interference.

While the intervention lasted six weeks, the participants were followed for 52 weeks.

Between February 2016 and March 2022, 347 participants were recruited, with a near-even split of males and females. Nineteen percent of participants in the opioid group and 15% of placebo subjects dropped from the trial by week 6, leaving 310 participants.

Mean pain score at six weeks was 2·78 in the opioid group versus 2·25 in the placebo group (p = 0·051).

Thirty-five percent of participants in the opioid group reported at least one adverse event versus 30% in the placebo group (p = 0·30), but more people in the opioid group reported opioid-related adverse events (7·5% versus 3·5% in the placebo group).

At 12 months, mean pain scores in the placebo group were slightly lower than in the opioid group (1.8 vs 2.4).

In addition, there was a doubling of the risk of opioid misuse at 12 months among patients randomly allocated to receive opioid therapy for 6 weeks. At one year, 20% of patients who received opioids were at risk of misuse, as indicated by the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) scale, compared with 10% of placebo patients (P = .049).

Despite widespread administration of opioids to spinal pain patients, there is pretty much zero valid research supporting their use for this purpose. Like so much of the porqueria peddled by Big Pharma, these drugs are marketed and prescribed largely based on wishful thinking.

This is a "landmark" trial with "practice-changing" results, senior author Christine Lin, PhD, told Medscape.

"Before this trial, we did not have good evidence on whether opioids were effective for acute low back pain or neck pain, yet opioids were one of the most commonly used medicines for these conditions," Lin explained.

On the basis of these results, "opioids should not be recommended at all for acute low back pain and neck pain," Lin said.

"We need to reassure doctors and patients that most people with acute low back pain and neck pain recover well with time (usually by 6 weeks), so management is simple ― staying active, avoiding bed rest, and, if necessary, using a heat pack for short term pain relief. If drugs are required, consider anti-inflammatory drugs," Lin added.

“Opioids should not be recommended for acute back and neck pain full stop," Lin stated in the University of Sydney press release. “Not even when other drug treatments are not able to be prescribed or have not been effective for a patient.”

The recently-published trial complements a 2016 review and meta-analysis that found opioids did not provide clinically meaningful pain relief in people with chronic low back pain.

So there you go. Another ineffective, life-wrecking product brought to you by Big Pharma and pushed by doctors who don't read the research, who write scripts first and ask questions later.

Medicine Loves its Useless, Toxic Junk

Whether these findings actually change anything remains to be seen. As evinced by the popularity of statins, antidepressants and the recent toxic gene therapy campaign, it seems the more dangerous and useless a drug is, the more likely it will be embraced by the world of medicine and become a blockbuster.

Despite a lack of scientific support, and despite all the devastation caused by prescription opioids, outfits like the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) are doggedly keeping the faith.

The IASP states: “Although opioids can be highly addictive, opioid addiction rarely emerges when opioids are used for short-term treatment of pain, except among a few highly susceptible individuals. For these reasons, IASP supports the use and availability of opioids at all ages for the relief of severe pain during short-lived painful events and at the end of life."

Hmmm, I wonder what might motivate IASP to defend opioids despite them being about as useful as a South Australian Police officer?

Despite its bleatings about impartiality, IASP and its members receive money from drug companies like Viatris, formed in 2020 via a merger between Pfizer's Upjohn and Mylan. The latter was among a number of companies targeted in a 2019 lawsuit for improper marketing of opioids.

Another IASP supporter is Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, which produces the opioid buprenorfine, along with methadone tablets for the treatment of opioid addiction.

Yet another IASP supporter is Novartis, the pharma giant whose antics include accidentally putting opioids into OTC products like Excedrin, Bufferin, NoDoz and Gas-X.

With a resume like that, I'd be far more inclined to rely on the research than 'position statements' from the likes of IASP.

Opioids are powerful, dangerous and addictive drugs. Don’t even begin to kid yourself otherwise.

Anthony's new book, Not So Fast: The Truth About Intermittent Fasting & Time-Restricted Eating is now available at at Amazon and Lulu.

Leave a Reply