Are your shoulder problems really caused by "impingement"?

Many of us will suffer shoulder pain at some point in our lives. After lower back and knee pain, shoulder pain is estimated to be the third most common reason for presenting to primary care with a musculoskeletal complaint (Lucas et al, 2022).

A large chunk of shoulder injuries are rotator cuff disorders. It’s become a default assumption that if you have a rotator cuff issue, the problem was caused and/or is being aggravated by “impingement”.

The Shoulder Impingement Syndrome theory holds that soft tissues in your shoulder get jammed between the bony structures. In turn, these soft tissues become “irritated”, “inflamed” and even torn. This allegedly leads to a vicious cycle where the inflamed and damaged tissues deteriorate even further thanks to continued “impingement”.

But is this actually true?

The content below was originally paywalled.

Shoulder injuries are common among athletes, particularly those participating in contact, strength, throwing, and “overhead” sports (Calhoon et al, 1999; Keogh et al, 2006; Okholm Kryger et al, 2015; Lin et al, 2018).

If you know anything about the shoulder complex, you won’t be surprised to learn rotator cuff damage is common among athletes presenting with shoulder injury (Cohen et al, 2007).

What may come as a surprise is that rotator cuff damage is also frequent in asymptomatic athletes. An MRI study of Ironman Triathletes presenting with shoulder symptoms found 19% had a partial tear of the rotator cuff, and 50% had tendinopathy. However, among a comparison group of asymptomatic Ironman triathletes, 29% had a partial tear of the rotator cuff and 29% had tendinopathy (Reuter et al, 2008).

Asymptomatic rotator cuff tears are also surprisingly common in the general population; prevalence of asymptomatic partial-thickness and full-thickness tears has been reported to range from 8% to 40% and from 0% to 46%, respectively (Lawrence et al, 2019).

The Impingement Bogeyman

Shoulder Impingement Syndrome is commonly blamed for these problems (Östör et al, 2005).

A survey of Australian chiropractors revealed “rotator cuff tendinosis/tendinitis with impingement” and “impingement syndrome” comprised 31% of their working diagnoses of shoulder pain (Pribicevic et al, 2009).

In a study of American collegiate and professional athletes with partial rotator cuff tears treated arthroscopically, all were diagnosed preoperatively as positive for “impingement” (Payne et al, 1997).

Among a sample of elite Italian volleyball competitors, 19% were deemed to have “impingement” in their the hitting shoulder (Monteleone et al, 2015).

Examination of the NCAA Injury Surveillance database found shoulder injuries were the most common type among collegiate wrestlers. “Shoulder Impingement” was the most common shoulder injury diagnosis, comprising 9.3% of all injuries (Goodman et al, 2018).

Clearly, medical practitioners and therapists are fond of blaming shoulder pain and rotator cuff problems on “impingement”.

Impingement? Or a Vulnerable Joint Pushed Beyond its Limits?

To really get a grasp of this whole “impingement” paradigm, a quick refresher on shoulder anatomy is in order. Don’t worry, I’ll make it brief.

There are in fact four articulations in the shoulder complex, but “shoulder impingement” invariably refers to problems at the glenohumeral joint. That’s the ball-and-socket configuration that allows you to swing your arms in circles. It’s the most mobile joint in your body.

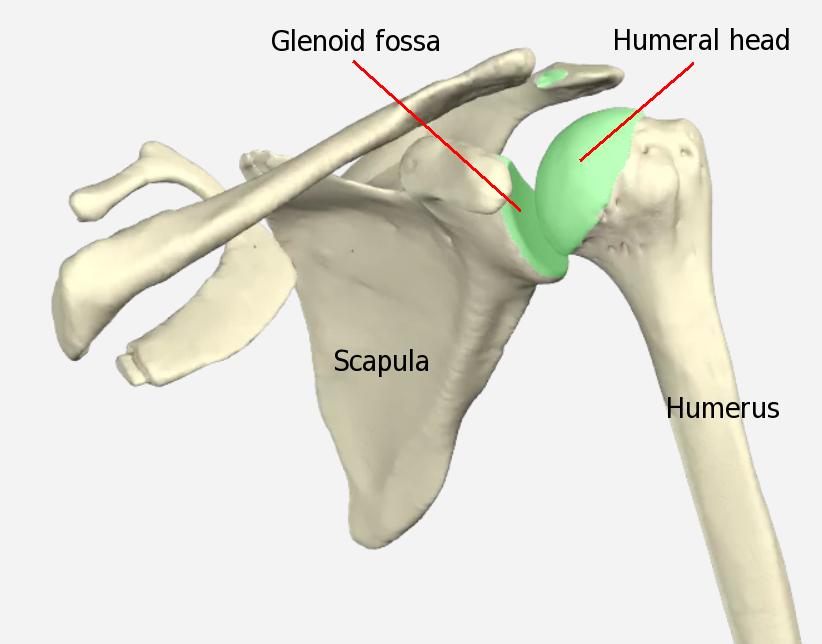

Unfortunately, the glenohumeral joint is also the most unstable joint in the body. The following illustration helps explain why. That area highlighted in green depicts the articular cartilage that lines the humeral head (the “ball”) and the glenoid fossa (the “socket”).

As you can see, not only is the concavity of the glenoid fossa quite shallow, but it features a much smaller surface area than the head of the humerus (your upper arm bone). Due to this mismatch, a maximum of 30% of the articular cartilage of the humeral head articulates with that of the glenoid fossa at any given time (Lugo et al, 2008).

It’s a configuration that confers the glenohumeral joint with an unusually large range of motion, but poor stability. As a result, the glenohumeral joint must rely heavily on a number of critical non-bone features to maintain stability.

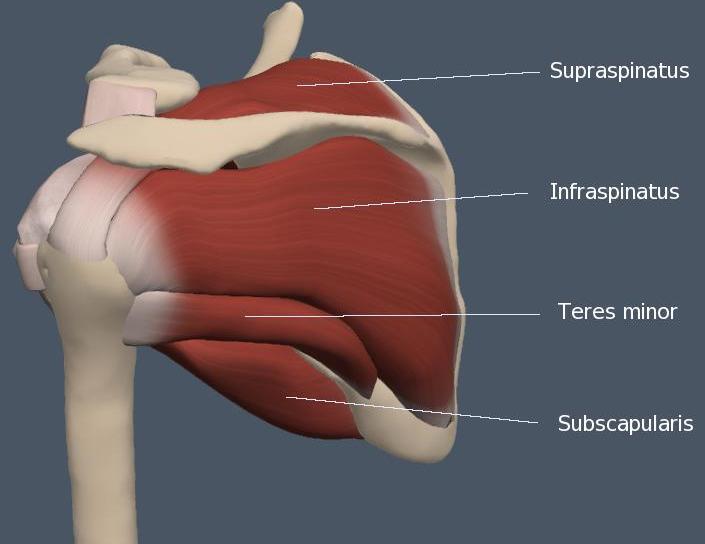

Most of those features - such as the glenoid labrum, glenohumeral ligaments, shoulder capsule and rotator cuff muscles - are relatively small.

The larger “prime mover” muscles surrounding the glenohumeral joint - notably the pecs, lats and delts - are something of a double-edged sword. They are important shoulder stabilizers (Nicolozakes et al, 2025), but also capable of generating high forces during movements that challenge the integrity of the glenohumeral joint.

Okay, But What Exactly is “Shoulder Impingement”?

Shoulder impingement at the glenohumeral joint is specifically termed “subacromial impingement”.

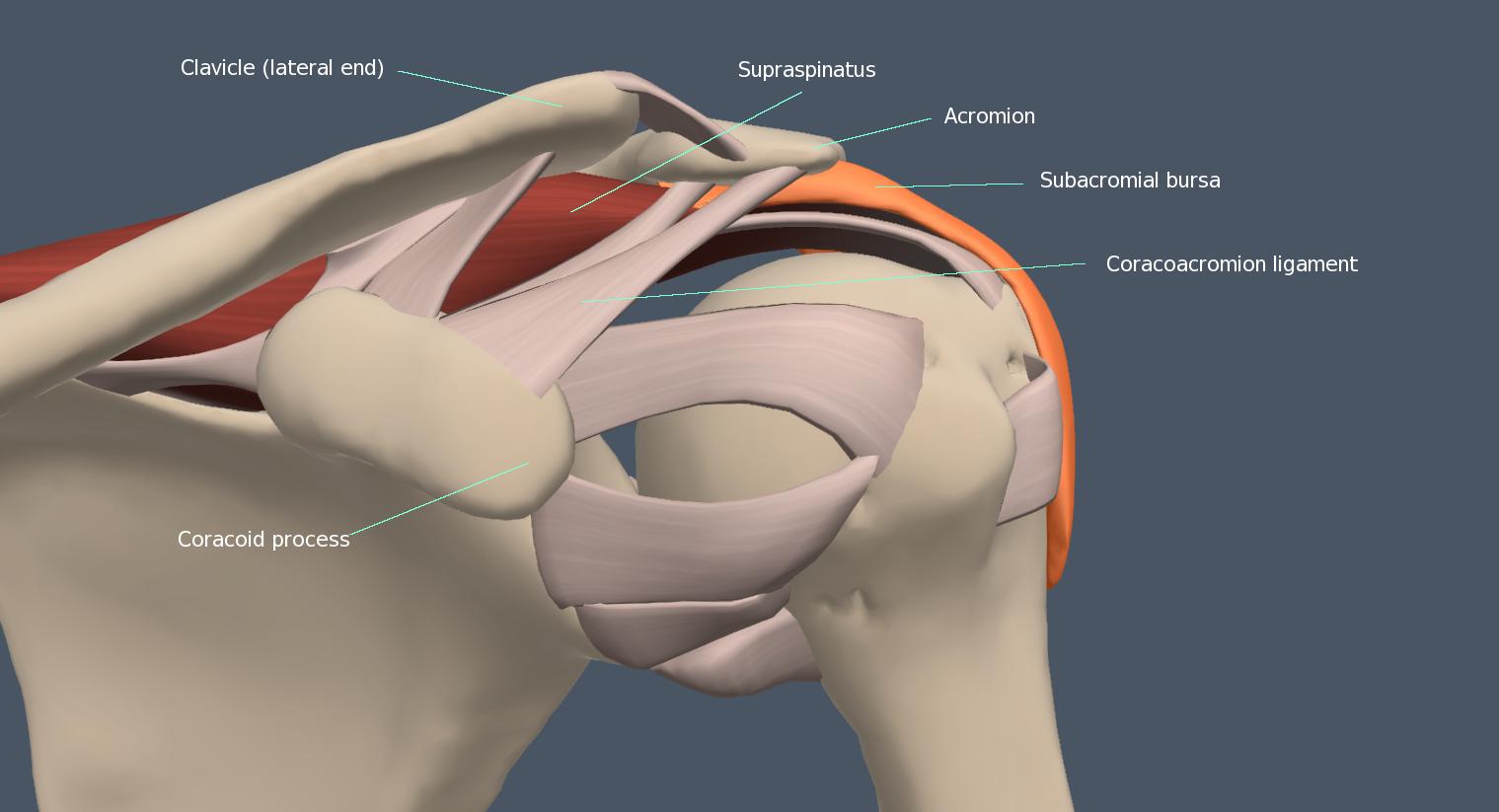

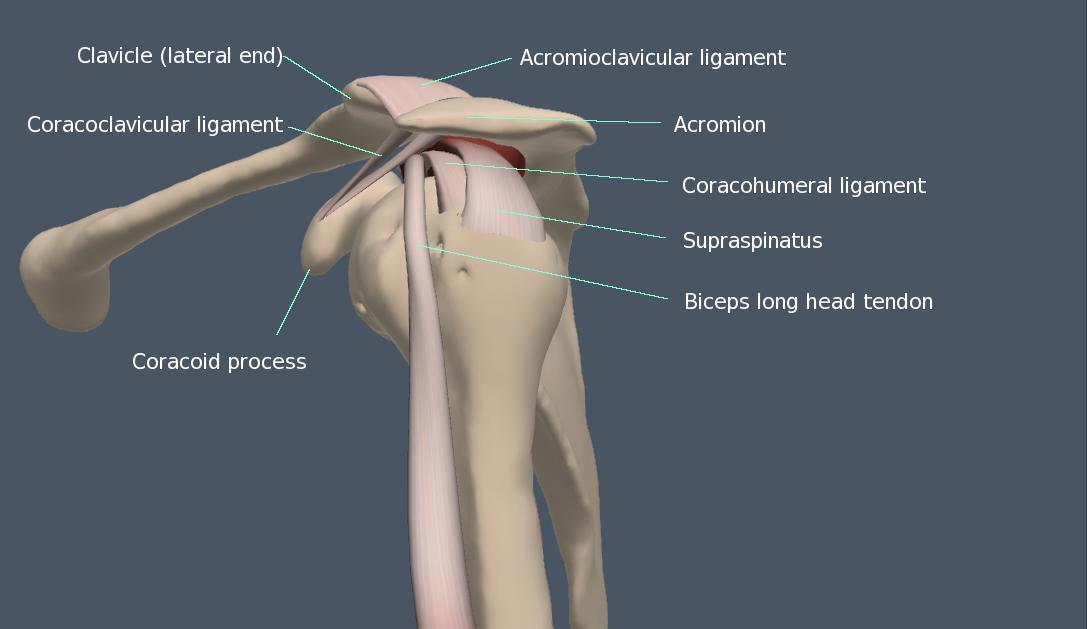

Central to the subacromial impingement theory is an area known as the subacromial space. That’s the narrow space between the humeral head, coracoacromial ligament, acromioclavicular joint, and acromion.

The height between the acromion and humeral head ranges from 1.0 to 1.5 centimeters (Umer et al, 2012). Located within this marginal subacromial space are rotator cuff tendons, the long head of the biceps tendon and subacromial bursa.

Figures 3 and 4 (below) depict front and side views of the glenohumeral joint; they show the aforementioned structures and help illustrate the narrow passage provided for soft tissues in the subacromial space.

That narrow gap, and the high incidence of rotator cuff injury, is what gave rise to the Shoulder Impingement Syndrome paradigm.

Subacromial impingement is said to occur when soft tissues in the subacromial space (rotator cuff, biceps long head tendon, and subacromial bursa) become compressed and inflamed between the bones and ligaments of the subacromial space.

This allegedly leads to disorders like rotator cuff tendinopathy, partial or complete tears, and inflammation of the subacromial bursa (Al Hammadi 2025).

The suprasinatus tendon is at highest risk for irritation and subsequent injury, supposedly because it is the most likely to contact the acromion when the arm is abducted (raised away from the body) and internally rotated (Graichen et al, 1999).

It should be pointed out at this juncture that the supraspinatus is the smallest of the all-important rotator cuff muscles.

So yes, there are soft tissues at the glenohumeral joint that must pass through a narrow gap. If that narrow subacromial space was the cause of so many shoulder problems, then it logically follows surgery to increase that space would be a great way to alleviate those problems.

Hacking Away at the Shoulder to Relieve “Impingement”

Impingement has been implicated in shoulder pathologies as far back as the 1850s (Adams, 1859); in 1939, the first known surgical excision of the acromion to treat supraspinatus tendon lesions was reported by Watson-Jones. The procedure involved partial and often complete removal of the acromion in order to eliminate contact between this structure and the humeral head (Armstrong, 1949).

The results were disappointing. There were also complications. This led late New York orthopedist Charles S. Neer II to develop a related procedure called acromioplasty that left the posterior acromion intact (Neer, 1972). Now commonly termed “shoulder decompression”, the procedure left the posterior portion of the acromion - which Neer deemed “innocent” of causing impingement - intact. Instead, anterior portions of the acromion along with the coracoacromial ligament were removed. During this procedure, bone spurs and soft tissue may also be excised if deemed to be causing “impingement”.

The Highly Popular Failure that is Acromioplasty

It is important to note no-one has ever proved subacromial impingement produces pathological changes in soft tissues at the glenohumeral joint. Despite this, acromioplasty incidence has experienced exponential growth, greatly outpacing the increase in other orthopedic ambulatory surgeries (Vitale et al, 2010; Judge et al, 2014).

This is despite a growing body of research showing decompression surgery confers no advantage over conservative treatment.

Randomised controlled trials conducted by Haahr et al (2005), Ketola et al (2017) and Paavola et al (2021) found decompression surgery demonstrated no advantage over exercise.

Stop and think about that for a moment: Surgery widens the subacromial space, exercise involves movements that narrow it.

Beard et al (2018), meanwhile, found the procedure conferred no clinically significant benefit when compared to no treatment.

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews found “High-certainty evidence shows that subacromial decompression does not provide clinically important benefits over placebo in pain, function or health-related quality of life” (Karjalainen et al, 2019).

In 2019, BMJ published a a clinical practice guideline in which the panel made “a strong recommendation against” subacromial decompression surgery. The guideline panel found surgery did not provide important improvements in pain, function, or quality of life compared with placebo surgery or other options. The panel concluded “almost all informed patients would choose to avoid surgery because there is no benefit but there are harms and it is burdensome.” (Vandvik et al, 2019)

Acromioplasty might be putting a lot of surgeons’ kids through college, and a lot of Mercedes in their garages, but the evidence shows it isn’t doing much good for patients.

Not So Squeezy

In addition to the failure of surgery, there is no concrete evidence subacromial space or structure increases risk of rotator cuff disorders.

For example, Lawrence et al (2020) compared symptomatic patients and subjects with no history of shoulder pain and found no relationship between the acromiohumeral distance and pain. Contact between the coracoacromial arch and rotator cuff tendon occurred in 45% of all participants during dynamic testing, with no difference between groups.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Park et al (2020) similarly found no relationship between the acromiohumeral distance and pain in adults with subacromial pain syndrome.

A Medical Myth

As a result of such findings, the subacromial impingement syndrome theory is being increasingly challenged. What is considered damage from “impingement” may in fact simply be damage from the strain, repetitive use, traumatic damage, and/or ageing of vulnerable tissues in the body’s most inherently unstable joint.

McFarland et al (2013) recommend the spectrum of rotator cuff abnormalities currently dubbed “impingement” instead be termed “rotator cuff disease”. They admonish that pain in the anterior and lateral shoulder should not be presumed due to impingement and instead termed “anterolateral shoulder pain”.

They note despite the frequent use of the term “tendinitis”, rotator cuff tendinopathy is characterized histologically by little evidence of inflammation. Instead, histological findings are more typical of a “failed healing response”, with haphazard proliferation of tenocytes, intracellular abnormalities in tenocytes, disruption of collagen fibers, and subsequent increase in non-collagen material. Some of these changes may be related to the normal ageing process of the tendon and soft tissues, which helps explain why rotator cuff tear risk increases with age and is most common in elderly populations (Yamamoto et al, 2010; Geary & Elfar, 2015).

They further note heavy physical loading, injury, vibration, infection, smoking, genetic factors, and fluoroquinolone antibiotics can produce such histologic features.

Lewis (2011) concludes “there is little evidence for an acromial impingement model” and “a more appropriate name may be ‘subacromial pain syndrome’”.

Papadonikolakis et al (2011) write: “It may be time to replace the nonspecific diagnosis of so-called impingement syndrome by using modern methods to differentiate tendinosis, partial tears, and complete tears of the rotator cuff.”

Braman et al (2014) similarly recommend the clinical diagnosis of “impingement syndrome” be eliminated as it is no more informative than the diagnosis of “anterior shoulder pain”.

Dhillon (2019) states subacromial impingement syndrome appears to be a “a medical myth” and “the impingement theory has become antiquated and surgical treatment should have no role in the treatment of such patients”.

So What to Do if You’ve Been Diagnosed With Shoulder Impingement?

The 2019 BMJ clinical guideline notes “substantial uncertainty” exists as to what alternative non-surgical treatment is best for disorders diagnosed as shoulder “impingement” issues (Vandvik et al, 2019).

Thankfully, there is a widespread consensus to employ conservative approaches as the first line of treatment.

Exercise

Based on available evidence, exercise should constitute the primary treatment for individuals diagnosed with “shoulder impingement”. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Steuri et al (2017) found although the quality of evidence was low, exercise interventions should be considered for all patients diagnosed with “shoulder impingement symptom”. Not surprisingly, shoulder-specific exercises were found to be more effective than non-specific exercises.

NSAIDs and Corticosteroid Injections

The Steuri et al analysis found NSAIDs had a small to moderate effect compared with placebo.

Like acetaminophen, NSAIDs are considered relatively innocuous and are available on supermarket shelves. Like the liver-toxic acetaminophen, NSAIDs should be used with caution (if at all). They increase risk of bleeding, heart attack, stroke, and kidney damage (Davis & Robson, 2016). UK hospital data found 30% of hospital admissions for adverse drug reactions were due to NSAIDs (Pirmohamed et al, 2004).

Steuri et al found corticosteroid injections were superior to no treatment, with ultrasound guided injections superior to non-guided injections.

In an umbrella review, Shen et al (2024) found while ultrasound guided injections to the shoulder joint generally yielded higher accuracy rates than landmark-guided injections, conflicting findings existed regarding their efficacy for pain alleviation and functional enhancement.

Other Treatments

All other conservative interventions examined by Steuri (manual therapy, hyaluronate, laser, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, ultrasound, pulsed electromagnetic field, TENS, myofascial trigger point therapy, acupuncture, diacutaneous fibrolysis, microwave, interferential light therapy and nerve block) showed either non-significant results or significant results but with very small sample sizes (n<100).

Using the GRADE “traffic light” rating approach, Steuri et al rated all the aforementioned modalities as “Orange: Uncertain effect—the effect of this intervention must be monitored, and alternative interventions need to be considered if the effect is not satisfactory.”

Kinesiotaping

Keenan et al (2017) found kinesiology taping did not aid nor impair shoulder strength, shoulder proprioception, or scapular kinematics in subjects presenting with clinical signs of “impingement”. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Araya-Quintanilla et al (2021) also found no effect of kinesiotaping on clinical outcomes in patients with “shoulder impingement syndrome” (bursitis, tendinopathy of rotator cuff and partial tear of supraspinatus).

Summary

“For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.”

- H. L. Mencken

The Shoulder Impingement Syndrome theory has an intuitive appeal to it: A bunch of important soft tissues pass through the narrow subacromial space, and can get jammed up and damaged when that space narrows.

It might sound logical, but there’s no evidence to support it. The subacromial impingement paradigm is based on an assumption; an unproven belief that the subacromial space is so narrow and inadequate that it frequently causes soft tissues passing through it to become irritated, inflamed and even torn.

The true causes of shoulder injuries ascribed to “impingement” are likely the same ones that cause soft tissue injuries in other parts of the body - things like acute trauma and strain, chronic repetitive strain, and ageing.

It should be remembered that soft tissues around the highly mobile glenohumeral joint - such as the small rotator cuff muscles - are expected to tolerate high forces and must support the humerus in extreme ranges of motion. They are tasked with keeping the humeral head in the glenoid fossa even when the humerus is moving at high velocity.

It’s not hard to understand why the glenohumeral joint is so prone to injury; one doesn’t need to concoct “impingement” theories to explain shoulder injuries.

The totality of the evidence indicates “shoulder impingement syndrome” and “subacromial impingement syndrome” are misleading, catch-all terms to describe shoulder pathologies that probably have nothing to do with impingement at all.

The good news is most people can achieve successful outcomes for the plethora of shoulder pathologies attributed to “impingement” through non-invasive means such as targeted exercise interventions.

Given the findings of randomized clinical trials, recommendations to undergo acromioplasty for “shoulder impingement” should be regarded with extreme caution.

References

Adams, R. (1859). Shoulder joint. In Bentley, T. R. (Ed) Cyclopedia of Anatomy and Physiology (Volume IV, Part I, pp. 571 – 621), Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts. Retrieved November 14, 2020, from https://archive.org/details/b21514227_0003/page/n3/mode/2up

Al Hammadi, M. I., Shah, Z. A., Rathod, R. K., & Seddik, M. A. (2025). Shoulder Impingement Pain Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and a Review of Current Treatment Strategies. Cureus, 17(9), e92045. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.92045

Araya-Quintanilla, F., Gutiérrez-Espinoza, H., Sepúlveda-Loyola, W., Probst, V., Ramírez-Vélez, R., & Álvarez-Bueno, C. (2022). Effectiveness of kinesiotaping in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 32(2), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.14084

Armstrong, J. R. (1949). Excision of the acromion in treatment of the supraspinatus syndrome. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 31-B(3), 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.31B3.436

Beard, D. J., Rees, J. L., Cook, J. A., Rombach, I., Cooper, C., Merritt, N., Shirkey, B. A., Donovan, J. L., Gwilym, S., Savulescu, J., Moser, J., Gray, A., Jepson, M., Tracey, I., Judge, A., Wartolowska, K., Carr, A. J., & CSAW Study Group (2018). Arthroscopic subacromial decompression for subacromial shoulder pain (CSAW): a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel group, placebo-controlled, three-group, randomised surgical trial. Lancet, 391(10118), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32457-1

Braman, J. P., Zhao, K. D., Lawrence, R. L., Harrison, A. K., & Ludewig, P. M. (2014). Shoulder impingement revisited: evolution of diagnostic understanding in orthopedic surgery and physical therapy. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing, 52(3), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-013-1074-1

Calhoon, G., & Fry, A. C. (1999). Injury rates and profiles of elite competitive weightlifters. Journal of Athletic Training, 34(3), 232–238. PMID: 16558570

Cohen, S. B., Towers, J. D., & Bradley, J. P. (2007). Rotator cuff contusions of the shoulder in professional football players: epidemiology and magnetic resonance imaging findings. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 35(3), 442–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546506295082

Davis, A., & Robson, J. (2016). The dangers of NSAIDs: look both ways. British Journal of General Practice: Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 66(645), 172–173. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X684433

Dhillon K. S. (2019). Subacromial Impingement Syndrome of the Shoulder: A Musculoskeletal Disorder or a Medical Myth? Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal, 13(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5704/MOJ.1911.001

Geary, M. B., & Elfar, J. C. (2015). Rotator Cuff Tears in the Elderly Patients. Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation, 6(3), 220–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/2151458515583895

Goodman, A. D., Twomey-Kozak, J., DeFroda, S. F., & Owens, B. D. (2018). Epidemiology of shoulder and elbow injuries in National Collegiate Athletic Association wrestlers, 2009-2010 through 2013-2014. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 46(3), 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2018.1425596

Graichen, H., Bonel, H., Stammberger, T., Englmeier, K. H., Reiser, M., & Eckstein, F. (1999). Subacromial space width changes during abduction and rotation--a 3-D MR imaging study. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy: SRA, 21(1), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01635055

Haahr, J. P., Østergaard, S., Dalsgaard, J., Norup, K., Frost, P., Lausen, S., Holm, E. A., & Andersen, J. H. (2005). Exercises versus arthroscopic decompression in patients with subacromial impingement: a randomised, controlled study in 90 cases with a one year follow up. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 64(5), 760–764. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2004.021188

Judge, A., Murphy, R. J., Maxwell, R., Arden, N. K., & Carr, A. J. (2014). Temporal trends and geographical variation in the use of subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair of the shoulder in England. Bone & Joint Journal, 96-B(1), 70–74. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.96B1.32556

Karjalainen, T. V., Jain, N. B., Page, C. M., Lähdeoja, T. A., Johnston, R. V., Salamh, P., Kavaja, L., Ardern, C. L., Agarwal, A., Vandvik, P. O., & Buchbinder, R. (2019). Subacromial decompression surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1(1), CD005619. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005619.pub3

Keenan, K. A., Akins, J. S., Varnell, M., Abt, J., Lovalekar, M., Lephart, S., & Sell, T. C. (2017). Kinesiology taping does not alter shoulder strength, shoulder proprioception, or scapular kinematics in healthy, physically active subjects and subjects with Subacromial Impingement Syndrome. Physical therapy in sport : Official Journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine, 24, 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2016.06.006

Keogh, J., Hume, P. A., & Pearson, S. (2006). Retrospective injury epidemiology of one hundred one competitive Oceania power lifters: the effects of age, body mass, competitive standard, and gender. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20(3), 672–681. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-18325.1

Ketola, S., Lehtinen, J. T., & Arnala, I. (2017). Arthroscopic decompression not recommended in the treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy: a final review of a randomised controlled trial at a minimum follow-up of ten years. Bone & Joint Journal, 99-B(6), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.99B6.BJJ-2016-0569.R1

Lawrence, R. L., Moutzouros, V., & Bey, M. J. (2019). Asymptomatic Rotator Cuff Tears. JBJS Reviews, 7(6), e9. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.RVW.18.00149

Lawrence, R. L., Braman, J. P., & Ludewig, P. M. (2019a). The Impact of Decreased Scapulothoracic Upward Rotation on Subacromial Proximities. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 49(3), 180–191. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2019.8590

Lewis, J. S. (2011). Subacromial impingement syndrome: a musculoskeletal condition or a clinical illusion? Physical Therapy Reviews, 16:5, 388–398. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743288X11Y.0000000027

Lin, D. J., Wong, T. T., & Kazam, J. K. (2018). Shoulder Injuries in the Overhead-Throwing Athlete: Epidemiology, Mechanisms of Injury, and Imaging Findings. Radiology, 286(2), 370–387. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2017170481

Lucas, J., van Doorn, P., Hegedus, E., Lewis, J., & van der Windt, D. (2022). A systematic review of the global prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 23(1), 1073. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05973-8

Lugo, R., Kung, P., & Ma, C. B. (2008). Shoulder biomechanics. European Journal of Radiology, 68(1), 16-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.02.051

McFarland, E. G., Maffulli, N., Del Buono, A., Murrell, G. A., Garzon-Muvdi, J., & Petersen, S. A. (2013). Impingement is not impingement: the case for calling it “Rotator Cuff Disease”. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal, 3(3), 196–200. PMID: 24367779.

Monteleone, G., Tramontana, A., Mc Donald, K., Sorge, R., Tiloca, A., & Foti, C. (2015). Ultrasonographic evaluation of the shoulder in elite Italian beach volleyball players. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 55(10), 1193–1199.

Neer II, C. S. (1972). Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder. A preliminary report. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 54, 41–50. PMID: 5054450.

Nicolozakes, C. P., Schmulewitz, J. S., Ludvig, D., Baillargeon, E. M., Danziger, M. S., Seitz, A. L., & Perreault, E. J. (2025). Muscles Functioning as Primary Shoulder Movers Aid the Rotator Cuff: Muscles in Increasing Active Glenohumeral Stiffness. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 53, 1328–1343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-025-03683-5

Okholm Kryger, K., Dor, F., Guillaume, M., Haida, A., Noirez, P., Montalvan, B., & Toussaint, J. F. (2015). Medical reasons behind player departures from male and female professional tennis competitions. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546514552996

Ostör, A. J. K., Richards, C.A., Prevost ,A. T., Speed C.A., & Hazleman, B. L. (2005). Diagnosis and relation to general health of shoulder disorders presenting to primary care. Rheumatology, 44(6), 800–805. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh598

Paavola, M., Kanto, K., Ranstam, J., Malmivaara, A., Inkinen, J., Kalske, J., Savolainen, V., Sinisaari, I., Taimela, S., Järvinen, T. L., & Finnish Shoulder Impingement Arthroscopy Controlled Trial (FIMPACT) Investigators (2021). Subacromial decompression versus diagnostic arthroscopy for shoulder impingement: a 5-year follow-up of a randomised, placebo surgery controlled clinical trial. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102216

Papadonikolakis, A., McKenna, M., Warme, W., Martin, B. I., & Matsen, F. A., 3rd (2011). Published evidence relevant to the diagnosis of impingement syndrome of the shoulder. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 93(19), 1827–1832. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.J.01748

Payne, L. Z., Altchek, D. W., Craig, E. V., & Warren, R. F. (1997). Arthroscopic treatment of partial rotator cuff tears in young athletes. A preliminary report. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 25(3), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354659702500305

Pirmohamed, M., James, S., Meakin, S., Green, C., Scott, A. K., Walley, T. J., Farrar, K., Park, B. K., & Breckenridge, A. M. (2004). Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 329(7456), 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15

Pribicevic, M., Pollard, H., & Bonello, R. (2009). An epidemiologic survey of shoulder pain in chiropractic practice in australia. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 32(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.12.005

Reuter, R. M., Hiller, W. D., Ainge, G. R., Brown, D. W., Dierenfield, L., Shellock, F. G., & Crues, J. V., 3rd (2008). Ironman triathletes: MRI assessment of the shoulder. Skeletal Radiology, 37(8), 737–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-008-0516-6

Steuri, R., Sattelmayer, M., Elsig, S., Kolly, C., Tal, A., Taeymans, J., & Hilfiker, R. (2017). Effectiveness of conservative interventions including exercise, manual therapy and medical management in adults with shoulder impingement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(18), 1340–1347. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096515

Umer, M., Qadir, I., & Azam, M. (2012). Subacromial impingement syndrome. Orthopedic Reviews, 4(2), e18. https://doi.org/10.4081/or.2012.e18

Vandvik, P. O., Lähdeoja, T., Ardern, C., Buchbinder, R., Moro, J., Brox, J. I., Burgers, J., Hao, Q., Karjalainen, T., van den Bekerom, M., Noorduyn, J., Lytvyn, L., Siemieniuk, R. A. C., Albin, A., Shunjie, S. C., Fisch, F., Proulx, L., Guyatt, G., Agoritsas, T., & Poolman, R. W. (2019). Subacromial decompression surgery for adults with shoulder pain: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 364, l294. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l294

Vitale, M. A., Arons, R. R., Hurwitz, S., Ahmad, C. S., & Levine, W. N. (2010). The rising incidence of acromioplasty. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 92(9), 1842–1850. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.I.01003

Yamamoto, A., Takagishi, K., Osawa, T., Yanagawa, T., Nakajima, D., Shitara, H., & Kobayashi, T. (2010). Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 19(1), 116–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.006

Leave a Reply