Can you get the same results in less time? Science - done properly - says yes.

As noted in Part 1, just how many sets one should perform in a gym workout is a source of often heated debate. Humans, you see, never run out of things to argue about.

If single sets deliver similar results to multiple sets, it means we can spend much less time in the weight room. We can get stronger and build a more muscular physique and have more time for other important things, like family, friends, hobbies, reading and learning, and pursuing other physical endeavours (cycling, hiking, martial arts, etc).

Is this ideal scenario possible, or merely wishful thinking of the have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too variety?

The content below was originally paywalled.

Dozens of RCTs have been performed on the topic, and it seems almost as many systematic reviews and meta-analyses of those RCTs have been published. Some reviewers, like Fisher, Carpinelli, Winnett, claim there is no evidence that multiple set training produces superior gains in strength and/or hypertrophy (muscle growth). Others, such as Krieger, Rhea, Ralston, conclude that multiple sets are superior for strength and/or hypertrophy gains.

A guide to the muddled state of research in this area can be gleaned from Krieger 2009, which states:

"In a dose-response model, 2 to 3 sets per exercise were associated with a significantly greater (effect size) than 1 set."

Debate settled, right?

Well no, because the next sentence declares, "There was no significant difference between 1 set per exercise and 4 to 6 sets per exercise or between 2 to 3 sets per exercise and 4 to 6 sets per exercise."(1)

So 1 set is inferior to 2-3 sets, which produce similar results to 4-6 sets, which produce similar results to 1 set.

Ugh. That's not real helpful.

I'm not having a go at James Krieger here; I believe he is an earnest researcher. His study was a meta-analysis and the self-contradictory conclusion reflects the limitations of that type of study.

A meta-analysis is where the results of multiple different clinical trials on a topic are combined into a sort of mathematical stew, and an overall risk estimate or effect size is obtained. This is helpful when the trials in question are fairly similar in demographics, methods and end results.

However, when you meta-analyze trials using vastly different methods and population groups, and - especially - reporting conflicting results, they are not so helpful. In a meta-analysis of RCTs with contradictory findings, it is possible to mathematically 'smooth' out the results and obtain a positive relative risk ratio or favourable effect size, even though the better quality individual trials included in the analysis achieved negative scores. This provides a misleading picture of the true state of clinical research in that area.

Because of their mathcentric nature, based as it is on numbers and not qualitative considerations, meta-analyses and systematic reviews often fail to adequately account for the myriad of inconsistencies and flaws that inevitably surface in clinical research.

Meta-Analysis versus Individual Analysis

Nothing will ever replace a careful, individual breakdown of each and every relevant trial on a topic. Unfortunately, doing the latter is highly time-consuming, especially on a topic where there may be dozens of eligible RCTs.

Today, I will be carefully breaking down what I consider to be some of the most important and insightful single versus multiple set RCTs, and it won't require a War and Peace-sized dissertation. That's because I've set some very basic inclusion interia that drastically trims the number of relevant studies. These are:

1. The inclusion of a group performing more than 3 sets. Despite it being common to see people doing more than 3 work sets of an exercise in gyms, the overwhelming majority of RCTs comparing set number have involved 1 set versus 3 set groups. Remarkably few RCTs have included groups performing more than 3 sets of an exercise.

2. RCTs with all male or all female participants (no mixed groups). All reality-defying woke nonsense aside, men and women are different, especially when it comes to their levels of endogenous anabolic hormones like testosterone. This ejects Nacliero et al 2013 from the discussion. That trial, for reasons unknown, included males and females in the same groups(2). The single set group featured 50% males, while the 2 and 6 set groups were 83% and 63% male, respectively. As a result, I'm not going to waste your time or mine discussing a study in which this most basic of variables was not effectively controlled for. The RCTs below featured males only; unfortunately, there are no healthy female-only RCTs involving > 3 sets.

3. Subjects that were organically healthy and fully ambulant at baseline. Specialized areas of weight training, such as injury rehabilitation or treating patients with chronic health conditions, are beyond the scope of this article.

Below is a discussion of all the relevant RCTs I could find that included a group performing 4 sets or more. A close look at these studies, especially the ones trumping the superiority of multiple sets, will provide valuable insight into just how effective single sets really are, and why at first glance the research in this area seems so conflicting.

Two of these studies found no difference between single and multiple sets for strength and/or hypertrophy, while the remaining 2 claimed superiority for multiple sets. As we go along, I'll explain how these studies may have arrived at such contradictory conclusions.

Single Set Training is Single Set Training

Before we kick things off, a little context-setting is in order. Some critics of HIT-style training claim that, because it involves warm-up sets (as any sensible weight training regimen does), it is not really single set training. This is disingenuous. Upon completion of one's warm-up sets, HIT typically involves a single work set to momentary muscular failure (and sometimes beyond). This is in stark contrast to standard practice in gyms all around the world, which is the performance of multiple work sets once one's warm-up sets are completed.

A similar criticism in this vein is directed at HIT routines with multiple exercises for the same bodypart. For example, a HIT thigh routine may contain a single work set each of squats, leg press, leg curls and stiff-leg deadlifts. HIT critics will counter that this is actually 4 sets, and therefore not single set training. Again, they would know full well that standard practice in gyms the world over is to perform multiple work sets of multiple exercises for a given body part. This is especially the case for bodybuilding-style routines, which are typically underpinned by a philosophy of working each muscle group from "different angles" in order to maximize muscular development.

HIT training has many variations, but the common theme is that it is built upon one work set per exercise, requires far lower volume and consumes far less time than traditional multiple set training.

Things Lifters Say

One other thing: Throughout this article, you’ll see the term “RM”, which stands for “Repetition Maximum.” A “1RM” is the maximum amount of weight you can lift for one repetition, or what’s known in lifting circles as a “single.” A 1RM is what you see lifters doing when you watch the Olympics or a powerlifting contest. It’s also a commonly performed strength test in resistance training studies, minus the smelling salts and standing ovations.

When preceded by a higher number, for example “8RM”, it refers to the maximum amount of weight that can be lifted for 8 repetitions.

If you see a number and the % sign accompanying the RM designation, e.g “50%RM”, it refers to 50% of one’s 1RM. So if the most you can deadlift for a single is 150 kg, your 50%RM is 75 kg.

Alright, with that out of the way, let the discussion begin.

Ostrowski et al 1997

Ostrowski et al from Southern Cross University in Lismore, Australia, randomly assigned 35 men to one of 3 groups: Low volume, medium volume, or high volume(3).

Irrespective of the volume, all groups performed 3 exercises per muscle group. The exercise selection was comprised of common free weight and machine movements. Each group followed a four-way split routine performed 4 days per week, meaning each bodypart was trained once a week. The training program ran for 10 weeks.

One group performed a single set of each exercise, another performed 2 sets, the other performed 4 sets of each exercise. Because each bodypart was trained with three exercises, this meant the low volume group performed 3 sets weekly for each bodypart, compared to 6 and 9 sets for the medium and high volume groups, respectively.

Thanks to the way the routine was structured, the single set low volume group was following a schedule reminiscent of the format used by 6-time Mr Olympia winner Dorian Yates.

All sets were performed to failure. All subjects performed around 12 reps per set for the first 4 weeks, 7 reps per set in weeks 5-7, and 9 reps per set in weeks 8-10.

Despite their otherwise thorough nature, the authors made no mention of what, if any, warm-up protocol was employed. No mention was made of what, if any, dietary instructions were given. Standard practice in these types of RCTs is to instruct the subjects to simply follow their usual dietary intake.

Each subject was tested before and after the 10-week program for hypertrophy, strength, power and even testosterone/cortisol concentrations.

The subjects were all currently weight training prior to randomization, and had been doing so for 1-4 years. After randomization, the three groups were fairly balanced in terms of baseline characteristics. Mean age and years of training experience were similar. The low volume group subjects were a mean 6-7 kg lighter than those in the other groups, while the low volume and medium volume subjects were slightly stronger at baseline compared to the high volume group.

Eight subjects dropped out of the study for reasons unrelated to the training program, leaving 9 subjects in each group.

The Results

After ten weeks, similar improvements were observed for all groups in 1RM strength. The increases in the low, moderate and high volume groups were 10 kg, 8 kg, and 14 kg, respectively for squat 1RM, and 3.6 kg, 4.5 kg and 1.6 kg, respectively, for bench press 1RM.

The researchers measured muscle growth by analyzing the quadriceps and triceps via ultrasound. Unlike other researchers, who are content to use a single image at the midpoint of a muscle, the researchers in this study also obtained additional images 5% below and above the midpoint. The researchers did this because previous studies have shown increases in size may not be uniform along the length of a muscle (anecdotally, this would be obvious to anyone who has followed bodybuilding or has any meaningful involvement in physique training).

I like reading this kind of thing in the methodology section of a study, because it indicates to me the authors possess the valuable but all-too-rare trait of commonsense (as the last 3 years have amply demonstrated, even highly decorated researchers can be utterly devoid of basic good sense).

Further evidence of Ostrowski et al's exacting approach could be evinced by their acknowledgement that ultrasound can be a subjective endeavour. So prior to this study, they conducted a pilot trial to validate the ultrasound operator's consistency by having him test 13 subjects 30 minutes apart. There were no significant differences in the two sets of images, so he made the cut for the subsequent training study.

The ultrasound results showed no differences in quadriceps or triceps hypertrophy between the 3 groups. Rectus femoris cross-sectional area increased by 6.7%, 5% and 13% in the low, medium and high volume groups, respectively. The corresponding increases for triceps brachia thickness were 2.3%, 4.7% and 4.8%, respectively.

Body mass increased by 2.0%, 2.6% and 2.2% in in the low, medium and high volume groups, respectively.

There were no significant changes in body fat thickness at the ultrasound sites, indicating that the body mass gain was primarily lean mass.

All groups showed similar improvements in power output and throw height on the bench press throw test, but no improvements were seen for vertical jump height or power output. The researchers speculated this conflicting result may have been due to the greater specificity of the bench press exercise and the bench press throw test, compared to the lower body testing.

After the 10-week program, testosterone concentrations rose slightly in the low and medium volume groups, but declined by a mean 37% in the high volume group.

Uh oh.

The low and medium volume group experienced an increase in the testosterone:cortisol ratio, a desirable change that may favour not just anabolism (recovery and growth) but overall wellbeing. The high volume group, meanwhile, experienced a decrease, from 2.8 to 1.2. None of these changes were statistically significant, but the effect size for the T:C ratio change in the latter group was large. The researchers proposed that the lack of statistical significance may have been an artifact of the small number of subjects in the study.

Due to its fairly thorough approach, I consider this one of the better currently available RCTs on the topic of set volume. It found 1 set of 3 exercises per bodypart, spread over a 4-way split in which each bodypart was trained once weekly, produced similar strength and hypertrophy gains as routines requiring 2 to 4 times the number of sets. It did so without triggering the potentially detrimental hormonal effects of higher volume routines.

Schoenfeld et al 2019

The next study was conducted by group of researchers that included Brad Schoenfeld, Bret Contreras and James Krieger (names that might be familiar to those of you who regularly visit strength training/bodybuilding websites). They recruited forty-five healthy male volunteer university students in their 20s who reported having trained consistently with weights at least 3 times per week for a minimum of 1 year(4).

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of 3 groups: a low-volume group performing one set per exercise per training session, a moderate-volume group performing three sets per exercise per training session, or a high-volume group performing five sets per exercise per training session.

The training protocol consisted of seven exercises per session: flat barbell bench press, barbell military press, wide grip lat pulldown, seated cable row, barbell back squat, machine leg press, and unilateral leg extensions. The inclusion of three thigh exercises meant that legs were trained with significantly higher volume compared to upper body parts in all 3 groups.

Training was "whole body" style, in which all exercises were performed in each session. All groups trained three days per week on nonconsecutive days for 8 weeks. Sets consisted of 8 to 12 repetitions carried out to the point of momentary concentric failure.

For muscle groups like the pectorals (chest), this translated into a total weekly number of sets per muscle group of 3, 9 or 15 for the 1, 3 and 5 set groups, respectively. Because of the unequal exercise prescription, the total weekly number of sets for thighs was 9, 27 and 45 for the 1, 3 and 5 set groups, respectively.

Once a subject completed more than 12 repetitions to failure in a given set, the load was increased. If less than eight repetitions were achieved, the load was decreased.

No mention was made of what, if any, warm-up protocol was used.

The subjects were advised to maintain their customary food intake. Most of these RCTs also require the subjects not to take any supplements or drugs, but in this study an exception was made: To help ensure that dietary protein needs were met, subjects consumed a supplement on training days providing 24 grams of protein (from whey protein isolate) and 1 gram of carbohydrate.

To prevent confounding, subjects were told to refrain from any additional resistance or high-intensity anaerobic training during the study.

Changes in strength were gauged with 1RM testing in the barbell parallel back squat and bench press.

Muscular endurance was assessed for the upper body only by performing the bench press with 50% of the subject's initial 1RM in the bench press for as many repetitions as possible with proper form.

To measure hypertrophy, single ultrasound images were used to determine muscle thickness on the right side of the body at four sites: 1) biceps, 2) triceps, 3) mid-thigh, and 4) outer thigh.

Eleven subjects dropped out of the study, with attrition fairly even among groups. This left 34 subjects in the trial, rendering it slightly statistically underpowered (the researchers had counted on at least 36 subjects in order to reliably achieve statistical significance).

This may be why there was no 'statistically significant' change in 1RM squat and 1RM bench press during the study, even though the subjects did in fact record mean increases in both lifts.

The Results

The mean increase in 1RM squat was 18.9 kg, 13.6 kg and 19.6 kg for the 1, 3 and 5 set groups, respectively.

The mean increases in 1RM bench press were 9.3 kg, 5.7 kg and 6.8 kg, respectively.

So again, we see the single set routine more than holding its own against the multiple set regimens in terms of strength increases.

Increases in bench press muscular endurance were modest and similar among all three groups. By the end of the study, the additional repetitions able to be performed with 50%RM on the bench were 3.1, 4.3 and 4.8 reps for the 1, 3 and 5 set groups, respectively.

At this point, it's worth noting that the average training times per session were approximately 13 minutes, 40 minutes and 68 minutes for the 1, 3 and 5 set groups, respectively. Despite spending 3 to 5 times longer in the gym, the 3 and 5 set groups failed to achieve any additional strength or muscular endurance gains.

If strength increases are your primary goal when training with weights, then these results suggest performing multiple work sets to failure is not a productive use of time. To the contrary, it looks a waste of time.

The ultrasound results, however, suggest a different story, and are worthy of further scrutiny.

The ultrasound-determined muscle thickness results at all four sites showed a stepwise increase with set number, suggesting a dose-response relationship between set number and muscle hypertrophy. With the exception of triceps, the differences in muscle thickness were statistically significant.

The most commonly cited rationale for the use of multiple sets is the claim that additional sets necessitate the recruitment of additional muscle fibers, causing greater damage or disruption, and hence triggering greater adaptation that manifests as muscle growth.

The lack of difference in strength gain could be explained by the fact that substantial increases in strength can occur in the absence of hypertrophy due to neural adaptations (improvements in "neuromuscular efficiency").

An uncritical analysis of the Schoenfeld et al results would suggest the occurrence of just such phenomena. However, there is another potential explanation for these results.

Anyone who knows anything about muscle growth knows that, in young, slimmish males, especially those with a mean 4.4 years' training experience (as in this study), significant muscle growth will necessitate an increase in bodyweight and hence require a surplus caloric intake.

In this study, the researchers reported "There were no significant differences between groups in changes in self-reported kilocalorie or macronutrient intake" (bodyweight changes were not reported in the paper).

The key words there are "significant" and "self-reported." Statistical significance is not the same as clinical significance, while self-reported dietary intakes are notoriously inaccurate and prone to underreporting, a fact that has been expounded upon in the published literature time and time again.

Dietary adherence for the study was assessed by self-reported food records using a nutritional tracking app (www.myfitnesspal.com), which was collected for two 5-day periods: 1 week before the first training session (i.e., baseline) and during the final week of the training protocol. In other words, the alleged dietary intake of the participants over the 10-week training period was determined by a single 5-day self-report compiled in the final week. Needless to say, relying on 5 days of self-reported food intakes to provide an accurate picture of 70 days' food intake is extremely optimistic. Some, including myself, would say unrealistic.

Suspicions of underreporting tend to be confirmed in this study by all the cited caloric intakes, which are unrealistically low for a group of healthy young males that averaged 82.5 kg at baseline and experienced muscle and strength gains during the study. At baseline, the alleged caloric intakes ranged from 1752 up to 2190 cal/day in the 1 and 5 set groups, respectively. During the final week, the alleged intakes ranged from 1790 up to 2168 in the 1 and 3 set groups, respectively.

Those are cutting intakes. In fact, the intakes claimed by the 1 set group are the kind I'd prescribe to small females seeking weight loss, not 80+kg males looking to build muscle.

When we look at the study table listing the mean self-reported nutritional data, we see that, at baseline, intake of calories, protein, and carbohydrates was sequentially higher in the 1, 3 and 5 set groups. During the trial, caloric intake barely changed in the 1 set group and rose slightly in the 3 set group, which is pretty much what you'd expect in light of the associated training volumes.

In the 5 set group, however, self-reported caloric intake inexplicably declined. Given that higher levels of activity are associated with greater appetite, this is a finding I hold with great skepticism.

Despite this anomaly, the self-reported caloric intake from the final week was still higher in the 3 and 5 set groups, compared to the 1 set group.

Self-reported protein intake was similar among groups in the final week, but there were notable differences in carbohydrate intake. The mean self-reported carb intakes from the final week were 148 grams, 205 g and 229 g, respectively.

And so we now have another important variable that, like the muscle thickness measurements, showed a stepwise increase with set volume. Given carbohydrate's stimulatory effect on insulin, and insulin's important role in anabolism, this is a finding that cannot be brushed off lightly, and which may explain the different hypertrophy outcomes.

For reasons I'll expound upon at the end of this article, dietary intake may be an important confounder not just in this trial, but in almost all RCTs comparing single and multiple set routines.

The Studies Claiming Superiority For Multiple Set Routines

Radaelli et al 2005

This study was conducted by researchers in Brazil but, interestingly, the paper's second listed co-author is US researcher Stephen J Fleck. Many years ago, Fleck co-authored a couple of weight training books with fellow exercise researcher William Kraemer(5). The latter has since become an avid low-carb diet advocate, even co-authoring a book with bombastic keto shill and now-disgraced hebephilic sex predator Jimmy "Livin' La Vida Low-Carb" Moore. I'm not sure whether Fleck still has anything to do with Kraemer, but the contents of their books indicate a definite and longstanding preference for multiple set training. This may or may not be of consequence, but multiple set advocates have pointed out that favourable studies by the likes of Winnett and Westcott (who has authored a number of books espousing single set training) may be influenced by those authors' pre-existing preference for low volume training. Therefore, I think its only fair to point out when the same possible bias maybe present in a study favouring multiple set training.

Anyway ... this study involved 48 young men of average height and weight from the Brazilian Navy School of Lieutenants (mean age 24.4 years; body mass 79.3 kg; height 174.5 cm). The subjects were experienced in traditional military training involving body weight exercises, but allegedly had no previous weight training experience.

The subjects trained for six months, completing 3 whole-body sessions per week with at least 48–72 hours of rest between sessions. They were randomly assigned to one of 3 training groups: 1 set, 3 sets, or 5 sets per exercise.

There were no free weight exercises used in this study. The training program consisted of the following Life Fitness machine exercises: Bench press, leg press, lat pulldown, leg extension, shoulder press, leg curl, biceps curl, abdominal crunch, and triceps extension, in that order.

The only warm-up protocol mentioned is “10 repetitions with approximately 50% of the resistance used in the first exercise of the training session." In the real world, this would be considered a grossly inadequate warm-up, but more on warm-ups in a subsequent installment.

During the actual workout, all training groups performed sets with a 8–12RM to concentric failure, with a rest interval of 90–120 seconds between sets and exercises. Once subjects were able to perform more than 12 repetitions in all sets of an exercise, the training resistance was increased by 5–10% for the next session.

In order to minimize confounding, the subjects were not allowed to perform aerobic or flexibility exercises during the 6-month training period.

The efficacy of the 1, 3 and 5 set programs were compared using the following before-and-after tests:

5RM on the machine bench press, leg press, lat pulldown and shoulder press (as a measure of strength);

20RM on the machine bench press and leg press (as a measure of muscular endurance);

Maximum height vertical jump (a commonly used marker of rapid power generation, or what is often referred to as "explosiveness"). Unlike Schoenfeld et al, who used a specialized machine, vertical jump in this study was tested the old-fashioned way; chalking one's hands, standing alongside a wall, and then jumping skyward for dear life and trying to tap the wall as high as possible.

To measure muscle growth, the researchers measured before-and-after muscle thickness of the biceps and triceps of the left arm only using ultrasound. The upper arm was the only area subject to ultrasound testing.

Body composition was assessed pre- and post-training using three skinfold caliper measurements (chest, abdomen, and thigh). Using these three site measurements, equations were employed to estimate percent body fat and fat-free mass.

The Results

To read the closing sentence of the abstract (which is as far as most people who read journals get), you'd think it was a clear win for the 5-set group:

"The results demonstrate a dose-response for the number of sets per exercise and a superiority of multiple sets compared with a single set per exercise for strength gains, muscle endurance, and upper arm muscle hypertrophy."

By declaring a "dose-response" relationship, the researchers were effectively claiming the more sets one performed, the greater their gains in the aforementioned variables.

Now let's see what the study really showed.

On the bench press, the 5RM of the single set group improved by a mean 8.7 kg during the 6 month program. The 3-set group improved by 12.7 kg, while the 5-set group improved by 10 kg. So on the bench press, a popular test of upper body strength and one of the three competition powerlifts, the 3 set group actually had the advantage, albeit a small one.

On the lat pulldown, the improvements for the 1, 3 and 5 set groups were 10.8 kg, 7.5 kg and 12.3 kg, respectively.

Shoulder press 5RM increased by 7.1 kg, 8.1 kg and 14.6 kg in the the 1, 3 and 5 set groups, respectively.

In the leg press - the exercise involving the most muscle mass in this study - the improvements for the 1, 3 and 5 set groups were 26.7 kg, 26.7 kg and 23 kg, respectively.

One thing that immediately stands out in contrast to the authors' claims is the piddling differences between groups, especially when considering the greatly increased training volume and time required by the multiple set interventions. By the end of the study, the 5 set group had to lift around 5.8 times the amount of weight in a session compared to the single set group - yet they got nowhere near 5.8 times the results. In fact there was no meaningful difference at all.

On a purely bang-for-buck basis, it's fair to say the 5-set routine was a fizzer.

The other thing that instantly jumps out, in stark contrast to what the researchers claimed, is the lack of a dose-response relationship. The 5-set group showed the greatest improvements only on the lat pulldown and shoulder press movements. The 3 set group showed the greatest improvement on the bench press, with a piddling mean difference of 1.3 kg between the 1 and 5 set groups after 6 months.

On the leg press, the 1 and 3 set groups showed an identical mean improvement, edging out the 5 set group by a mean 3.7 kg.

If that is a dose-response relationship, then my name is Fred Flinstone.

For the 20RM bench press, the increase in 1, 3 and 5 set groups was 1.7 kg, 7.3 kg and 11.1 kg, respectively.

For the 20RM leg press, the increase in 1, 3 and 5 set groups was 10.9 kg, 7 kg and 34.6 kg, respectively.

While the 1 and 3 set results were conflicting, there was a clear advantage for the 5 set group for the 20RM - a rep range that many trainees never venture into, because they tend to be more interested in strength and/or hypertrophy than local muscular endurance. Improved muscular endurance as a result of multiple set training has been confirmed in some studies and refuted in others (eg Schoenfeld above). I won't spend time discussing it because most folks who lift weights do so to improve their strength and get buff, not to increase muscular endurance.

When it came to power, all the groups increased their vertical jump by an inch or so, with no significant differences between groups.

Upper arm muscle thickness, as measured by ultrasound, increased slightly in the 5 set group but not the 1 or 3 set groups.

Body fat percentages declined by a similar amount in all three groups.

Fat free mass increased in all groups, with a non-significant dose-response trend. Mean FFM gains in the 1, 3 and 5 set groups were 0.46 kg, 2.98 kg and 3.32 kg, respectively. A fourth control group that did no weight training, only bodweight exercises, gained a mean 2.91 kg of lean mass despite no strength improvement. These results need to be interpreted with caution as they were deduced using skinfold calipers, which can be subject to both intra- and especially inter-tester variation (whether the same tester performed before and after skinfold measures on all the subjects, was not stated).

While the authors declared a win for multiple set training, there was an important potential confounder present. Before the training commenced, a neat, stepwise increase in baseline 5RM could be observed for all exercises in those assigned to the 1, 3 and 5 set groups, respectively. So the 3 set group started out with greater upper body strength than the single set group, and the 5 set group kicked off with an even greater upper body strength advantage. In most cases, the differences were substantial. For a study in which the subjects were supposedly randomized, this is unusual. The difference was least pronounced in the leg press, which just happened to be the exercise where the post-training changes showed the least difference among groups.

This raises the possibility that the trend for greater increases in 5RM for upper body exercises among the 3 and 5 set groups may have had more to do with the subjects' initial upper body strength than with the number of sets they were assigned to. Did the multiple set subjects, on average, possess a greater genetic potential for upper body strength gains than those in the single set group?

Or were some of the subjects more experienced in weight training than the paper would have us believe? It is common for weight trainees, especially beginners, to focus on the ‘show muscles’ of the upper body and skip leg training. Was there such a history among the trainees in this study? If so, by accident or design, were a greater number of those experienced in upper body training, and hence more familiar with bench press execution, assigned to the multiple set groups?

Some may think I'm being pedantic or making unfair insinuations, but these are questions that need to be asked when a study's results don't add up.

Given the discrepancies, the mixed 5RM results, lack of vertical jump improvement, and the less-than-exhaustive method for determining hypertrophy, it is difficult, if not untenable, to recommend multiple set training on the basis of this study. Spending vastly greater times in the gym and subjecting your muscles and joints to almost six times the poundage in the pursuit of such meager differences - even if those differences are genuine - can hardly be considered an intelligent deployment of time and energy.

Incidentally, two previous studies by Radaelli et al (not involving Fleck) found similar increases in 1RM, isometric strength and lower- and upper-body muscle thickness in elderly women assigned to either 1 or 3 set training for 6 and 13 weeks(6,7).

Marshall et al 2011

This paper, authored by a trio of Australian and New Zealand researchers, also purported to find a 'dose-response relationship' between number of sets and strength increases(8).

The study began with 43 healthy, resistance-trained males (mean 28 years, 178 cm, 84 kg) with a mean training experience of 6.6 years. Eleven subjects withdrew from the study, leaving 32 men that completed the full training program.

After an initial 2-week familiarization training phase, the participants were randomly assigned into one of 3 groups for a subsequent 6-week training period in which the barbell back squat was the only lower body exercise prescribed. During this six week period, all participants performed the same multiple set upper body program, but prescription of squat volume varied according to group assignment: 1 set, 4 sets or 8 sets.

For the 6-week training period, subjects trained 4 days a week using a 2-way split routine, so that each muscle group was trained twice weekly.

The squats were to be performed at a weight equaling 80% of each subject's 1RM. All sets of squats were reportedly performed to "volitional exhaustion." The official definition of "volitional exhaustion" (aka volitional fatigue) is pretty much identical to that for momentary muscular failure, which is the point you can no longer complete another rep in good form. It's a curious term, because the word "volitional" means to make a conscious choice. As we'll learn shortly, choosing when to stop a set, rather than continue to the point where one could not squeeze out another rep in good form no matter how hard one tried, is exactly what the multiple set groups appeared to do during their squat workouts.

The squats were performed with 3-minutes rest between sets. Subjects performed the following warm-up protocol prior to the squat working set/s: A set of 10 bodyweight squats, followed by a 10 rep set at 50%RM, then single repetitions at 60% and 70%RM.

Following the six-week training period, there was a further 4-week period during which all participants performed the same exercises and number of sets. This program combined traditional weight training movements (4 exercises per session, 4–12 RM), with ballistic exercise movements (2 exercises per session of either jump squat, bench press throw, dumbbell snatch, barbell push-press).

Again, four sessions per week were performed during this period, with each muscle group trained twice weekly. All participants executed the same squat routine during this phase, with 3 sets of 4RM.

The Results

During the 6-week training phase, squat 1RM increased by 16.5 kg, 20.9 kg and 32 kg in the 1, 4 or 8 set groups, respectively. These are unusually large gains, especially for subjects who have already been training, on average, for over 6 years. We'll talk about that a little more in a moment.

The subsequent 4-week phase was designed to test whether a period of reduced volume, at least for the 4 and 8 set groups, would produce a further "rebound" effect. This would appear to be the case for the 8 set group, whose mean 1RM improved by a further 5kg compared to less than 1 kg in both the 1 and 4 set groups.

Body fat percent, as determined by skinfold caliper measurements, declined similarly in all groups (2.0%, 1,8% and 1.6% in the 1, 4 or 8 set groups, respectively).

During the 6-week phase, body weight underwent little change, with mean gains of 0.3 kg and 0.6 kg in the 1 and 5 set groups, and a 0.5 kg loss in the 3-set group. During the 4-week "rebound" phase, the 1 set group gained a further 0.2 kg, the 4 set group lost a further 0.2 kg, while the 8 set group gained another 0.9 kg.

There were no differences between groups for quadriceps torque or rate of force development (measured by isokinetic dynamometer), or quadriceps femoris activition (as measured by EMG).

The researchers did not make any attempt to measure thigh hypertrophy in the three groups, so this study tells us nothing about whether 1, 4 or 8 sets is better for making your thighs swole.

The sole finding of note is that 8 sets of squats produced markedly greater 1RM gains than single set training. Four sets produced a slightly greater but non-significant 1RM gain compared to 1 set, again suggestive of a dose-response relationship.

A Fail on the Rapid Sniff Test

When I read this study closely, alarm bells started ringing almost immediately.

I have been involved with weight training for almost forty years, a period in which I've been both a trainee and trainer. After four decades of experience, there is one thing I and most other competent trainers would never do, and that is tell our trainees to perform 8 sets of squats to failure in a single workout. The reason is simple: Squats are difficult, and require above average focus. Eight sets of squats presents a high risk of acute fatigue, and with fatigue comes the risk of reduced focus and deteriorating form. On an exercise where you may have hundreds of kilos of iron perched atop your shoulders, that is the last thing you want.

In addition to the short term injury risk, eight sets of such a demanding exercise, performed twice a week, would be a great way to scorch your central nervous system and trigger a case of overtraining syndrome.

To anyone reading this study and contemplating doing 8 sets of squats to failure twice a week, my advice is:

Don't.

So how did the eight set participants in this study manage it?

A close look at the data reveals two main methods: By squatting shallow and avoiding failure - contrary to the study protocol.

The squats in this study were really half squats, as "All squats were performed to a depth of 90° knee flexion."

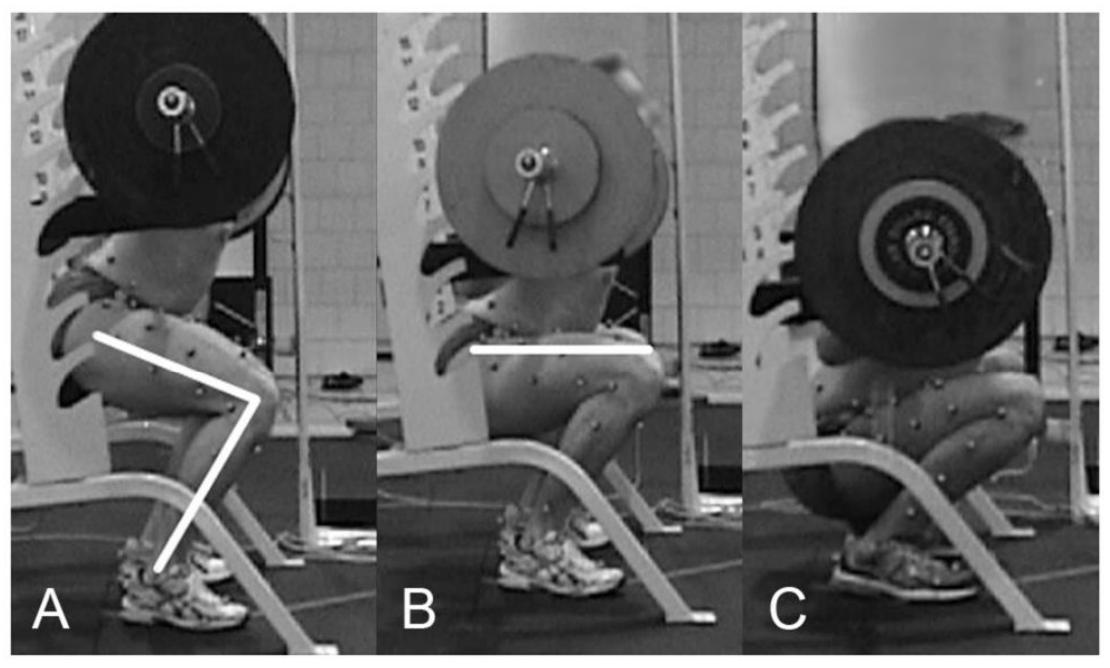

If you don't know what that looks like, here's a visual guide of three different squat depths*:

Image A is an "above parallel squat" and derived in a study where, on average, subjects squatted to a knee flexion angle of 98.7° for the above parallel squat(9). So a squat involving 90° knee flexion would be even shallower than this already partial squat.

Image B is a parallel squat producing an average knee flexion angle of produces a knee flexion angle of 123.7°. This is the kind I recommend for most people, the version I have observed to be most productive, and the kind that leaves you puffing like a steam train when performed with heavy weight for 8 or more reps.

Few would argue that a half squat is as difficult as a squat to parallel, even though the former allows you to use more weight. Squatting to parallel involves travelling further down, and enduring a longer fight against gravity in order to return to the upright position.

Assuming most of the subjects were used to squatting to parallel or below, as most gym trainees who squat are, then acclimation to the half-squat could explain the unusually large 1RM increases seen in this study. Learning a new exercise, or a variation of an existing exercise, is usually when you make the most rapid strength increases in that movement, as your neuromuscular efficiency in that movement improves.

Not only did the subjects perform a half-squat, but the multiple set groups appear not to have trained to failure. When the researchers tallied the average number of reps the subjects did on the first squat work set of each session, they observed the following:

1 set group: 10.9 reps

4 set group: 9.0 reps

8 set group: 8.2 reps

What this indicates is that the 4 and 8 set groups did not go to failure or exhaustion on each and every set, but in fact held back 2-3 reps short on their first set in the knowledge there were still numerous more sets to come.

Some of you might be thinking, "ok, that's all interesting, and helps explain the uncharacteristic strength increases and why the 8 set group didn't collapse in a heap, but that group still had the greatest 1RM squat increase."

Which brings me to my next pertinent observation.

Similar to the Brazilian study, this RCT was again marred by baseline discrepancies that should have been eliminated during the randomization process. Again, there was a neat, stepwise and inexplicable increase in baseline squat 1RM for the 1 set, 4 set and 8 set groups, in that order. While body fat % was similar among all three groups, the baseline bodyweight for the single set group (79.5 kg) was over 5kg lighter than the 4 set (84.8 kg) and 8 set (85.2 kg) groups. This raises the possibility that the multiple set groups were populated by a higher proportion of "mesomorphs" (a body type associated with higher natural levels of strength and muscularity) or otherwise high-responders.

Per chance, the researchers just happened to consider this possibility themselves. Based on the individual 1RM gains observed among subjects, the researchers found there were high and low responders in each of the randomized training groups. However, a greater number of high responders (those whose squat 1RM increased by a mean 29.4%) were from the 4 and 8 set groups, while 6 of the 13 low responders (whose 1RM squat increased a mere 2.6%) were from the single set group. These numbers do not establish whether the responder status existed at baseline and influenced the subsequent 1RM results, or whether the number of sets influenced the subsequent 1RM responses. The differences in baseline strength and bodyweight tend to add credence to the former proposition.

As noted, this discussion focuses on RCTs that examined >3 sets per exercises, but a perusal of the 1 versus 3 set RCTs reveals that unequal randomization seems unusually common in this area of research. Rhea et al 2002 compared single versus multiple sets in young men with a minimum of 2 years' training experience, and concluded "3 sets of training are superior to 1 set for eliciting maximal strength gains."(10) Rhea et al wrote: "In this study, the only difference between [1 set] and [3 set] groups was the training volume." Well, that's not true: Despite similar heights and body fat percentages in both groups, the men in the 3 set group were far heavier at baseline; a mean 97 kg compared to 83 kg in the single set group. That's a large difference, and strongly suggests a higher proportion of mesomorphs in the 3 set group. It also raises questions of whether some of the subjects in the 3 set group were enjoying pharmaceutical assistance. Although anabolic drug use is an important potential confounder, subjects in most resistance training studies are not drug tested, no doubt due to the extra expense involved. Participants are simply asked via questionnaire during recruitment whether they use any supplements or drugs, and the researchers assume they are telling the truth when they say no.

The Rhea paper contains a number of other eyebrow-raising statements. Training appears to have focused on the leg press and bench press, yet sessions took "about 1 hour" to complete. That's an inordinate amount of time to complete a mere 3 sets of bench and 3 sets of leg press, let alone a single set of each.

The researchers claim the 3 set group "was limited to 1–2 minutes rest between sets," which leaves one wondering why on Earth the sessions took so long.

Then we learn that Rhea et al employed some rather odd training methodologies to pass the remaining time. I'll let them explain in their own words:

"Because the [single set] group completed the prescribed exercises in less time than the [3 set] group, they were assigned to perform 1 set (8–12 repetitions) of exercises unrelated to the bench press and leg press. These exercises included biceps curl, lat pull-down, abdominal crunches, back extensions, and seated rows. Any remaining time was used for flexibility exercises. Time permitting, the [3 set] group also performed these same exercises for only 1 set."

This was supposed to have been a study comparing two identical routines differing only in the number of sets per exercise. Instead, it degenerated into something of a haphazard affair in which, to fill time, the single set group did extra exercises and the multiple set group dabbled in some single set training.

Training people is not like childcare, where you have to keep kids occupied and amused for a set period of time. The major premise underpinning single set training is to achieve the same results in less time.

How this affected the results is anyone's guess, but the bottom line is that the researchers introduced other variables into what should have been a straightforward comparison of single versus three sets.

Then there was the paper of Schlumberger et al, who conducted a 6-week RCT with German women aged 20-40 possessing at least 6 months of regular weight training experience(11). They concluded their "findings suggest superior strength gains occurred following 3-set strength training compared with single-set strength training." Despite being shorter, the women in the single set group were a mean 8.5 kg heavier than the women in the 3 set group. Body fat % were not stated, but given these were women with basic training experience training at a commercial "ladies gymnasium," it's fair to assume the difference in weight was very likely not muscle. Again, this raises the possibility of unfavourable genetics or differences in motivation or training experience affecting the results of the single set group.

The frequency of lopsided groups despite randomization may be an artifact of the small numbers of subjects in these studies, which could have been swayed by relatively small numbers of "outlier" subjects whose characteristics deviated from the mean. It is very curious, though, that potentially disadvantageous characteristics always seemed to predominate in the single set groups.

There is one other line of evidence which causes me to hold the results of the Marshall et al study with great skepticism. Some of you may have heard of German Volume Training, a routine that involves performing ten sets of 10 reps per exercise. This routine was popularized by the late supplement grifter and trainer Charles Poliquin. If that's not reason enough for you to avoid it, University of Sydney researchers compared GVT to a 5-set routine, and found the latter produced greater lower and upper body strength gains among groups that were more evenly matched at baseline(12).

So that study found 5 sets was better than 10, while the lopsided Marshall et al trial claimed 8 sets was better than 4.

Summary

An analysis of four RCTs is not going to conclusively settle the debate on single versus multiple sets, especially when they achieved different conclusions. However, these studies do reveal some very important findings.

The first is that single set training is effective for increasing strength, even in subjects with prior training experience. Not only does it work, but in the two studies not tainted by substantial baseline strength and bodyweight discrepancies, single set training produced similar strength increases, as measured by 1RM improvements, as did multiple set training.

These studies also indicate that, even if you train with multiple sets of an exercise, most if not all your strength gains for that exercise are coming from your first work set.

These studies also show that single set training is an extremely time efficient method of strength training. Not only does it dramatically reduce the amount of time you need to spend in the weight room, it also reduces the total poundage you lift in a session, potentially reducing the risk of central nervous system burnout and muscle and joint injuries.

As for the comparative effects of single and multiple sets on hypertrophy, the waters become muddied. Of the four aforementioned studies, 3 measured hypertrophy (all by ultrasound). The study involving the most thorough ultrasound procedures (Ostrowski et al) found no significant differences in hypertrophy among groups.

Schoenfeld et al and Radaelli et al found greater increases in muscle thickness with increasing sets, but both studies feature baseline discrepancies with the potential to differentially affect muscle hypertrophy.

The calorie and carb discrepancies seen in the Schoenfeld bring us to an important limitation of most free-living resistance training studies: Dietary intake.

It has long since been established that significant strength increases can occur in the absence of measurable muscle hypertrophy. Which explains why, in RCTs like those discussed above, single set groups can demonstrate similar strength increases yet much smaller muscle thickness increases when compared to multiple set groups.

In non-overweight individuals, which would describe most of the subjects in the above studies, adding any meaningful amount of muscle mass means increasing one's bodyweight. To increase one's body weight - whether it be via an increase in muscle mass or adipose tissue - requires a hypercaloric diet supplying an 'excess' of energy intake(13).

Compared to endurance training, relatively little research has been done on the effect of resistance training on appetite. Researchers from Iran report that a 3-day-per-week whole body routine of 3 sets per exercise significantly increased appetite in previously sedentary but otherwise healthy men(14).

Research involving endurance training shows that as the intensity and hence calorie burn of exercise increases, so too does appetite and caloric intake(15).

What's my point in mentioning all this?

In studies comparing different set volumes on strength and hypertrophy, the nutritional instruction invariably given to study subjects is to maintain their usual dietary habits.

That's not such a big deal for strength, which can improve significantly even in the absence of hypercaloric intakes or notable increases in body weight.

A meaningful study of hypertrophy in normal-weight subjects, however, would necessitate instructions for each subject to increase their daily caloric intake so that a surplus over their maintenance caloric requirements (at least an extra 400 calories per day)(16).

In a study where subjects are not given such instruction but simply told to keep eating as usual, that's not going to happen. Instead, left to their own devices, these subjects will be guided by their own appetites, and their subsequent caloric intake will be heavily influenced by their exercise volume.

I suspect this is what may be happening in studies purporting to show greater hypertrophy gains on multiple set routines. Scientific confirmation of my suspicions would require single versus multiple set RCTs in which subjects were instructed to increase their caloric intake, to a degree that created at least a 400 calorie daily surplus above their daily energy burn.

Gold standard confirmation would be in the form of metabolic ward trials, but given the increasing cost of everything and the prioritization of research funds to studies supporting commercial and political agendas, don't expect that to happen anytime soon.

In the meantime, anyone of normal or below normal weight wishing to achieve hypertrophy from single (and multiple) set routines should strongly consider eating a bare minimum of an extra 400 calories per day above their maintenance caloric intake. As I'll elaborate in a future article, once your protein needs have been met, and assuming you are not a dietary fat-phobe, the extra calories are best sourced from carbohydrates.

Outside the lab, empirical evidence demonstrates that one can achieve significant muscle mass gains with single set routines. Dorian Yates even used this style of training to win bodybuilding's most coveted title - Mr Olympia - six times in a row. Yes, he was using anabolic drugs, but so were all his competitors. The fact that he's still alive, healthy and active - compared to many of his former competitors who are now either dead, severely injured or sporting transplanted organs - suggests his use of anabolics was on the conservative side for a 1990s pro bodybuilder.

As for genetics, most observers of 90s bodybuilding agree that folks like Flex Wheeler (who later required a kidney transplant) had more favourable natural physical attributes. What Flex didn't have was Dorian's oxen-like tenacity and work ethic. Through "blood and guts" training and the use of HIT principles, Yates not only surpassed Flex in muscular development but ushered in the "mass monster" era with his awe-inspiring dimensions.

Another thing that Yates (and "Heavy Duty" icon Mike Mentzer) did was to regularly employ "set extender" or "high intensity" techniques, like forced reps, rest pause and negatives. In my next article on this topic, we'll take a closer look at one such technique that can be safely used by people training alone.

Until then, train smart,

Anthony.

*Image C is a below parallel or "deep" squat, producing an average angle 140.5°. I don't recommend this squat, the main reason being the increased coordination and pelvic tilt required to eke out the several extra inches of movement greatly reduces the poundage you would otherwise lift in a parallel squat, in turn reducing the potential strength and hypertrophy gains. Yes, Olympic lifters regularly squat deep, but with poundages they can hoist overhead (ie not maximal squat weights). And yes, young kids and primitive villagers often crouch in a deep squat position, but playing with Lego while in an unloaded deep squat and trying to emerge from that same position with 140kg or more of clanging iron balancing on your traps are two very, very different things. Just ask your knees.

References

1. Krieger JW. Single versus multiple sets of resistance exercise: a meta-regression. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2009; 23 (6): 1890–1901.

2. Naclerio F, et al. Effects of different resistance training volumes on strength and power in team sport athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2013; 27 (7): 1832–1840

3. Ostrowski KJ, et al. The Effect of Weight Training Volume on Hormonal Output and Muscular Size and Function. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 1997; 11 (3): 148–154.

4. Schoenfeld BJ, et al. Resistance Training Volume Enhances Muscle Hypertrophy but Not Strength in Trained Men. Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, 2019; 51 (1): 94–103.

5. Radaelli R, et al. Dose-response of 1, 3, and 5 sets of resistance exercise on strength, local muscular endurance, and hypertrophy. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2005; 29 (5): 1349–1358.

6. Radaelli et al. Low- and high-volume strength training induces similar neuromuscular improvements in muscle quality in elderly women. Experimental Gerontology, 2013; 48: 710–716.

7. Radaelli et al. Effects of single vs. multiple-set short-term strength training in elderly women. AGE, 2014; 36: 9720.

8. Marshall PWM, et al. Strength and neuromuscular adaptation following one, four, and eight sets of high intensity resistance exercise in trained males. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 2011; 111: 3007–3016.

9. Cotter JA, et al. Knee Joint Kinetics in Relation to Commonly Prescribed Squat Loads and Depths. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2013; 27 (7): 1765–1774.

10. Rhea MR, et al. Three Sets of Weight Training Superior to 1 Set With Equal Intensity for Eliciting Strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2002; 16 (4): 525–529.

11. Schlumberger AJ, et al. Single- vs. multiple-set strength training in women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2001; 15 (3): 284–289.

12. Amirthalingam T, et al. Effects of a modified German volume training program on muscular hypertrophy and strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2016; 31 (11): 3109–3119.

13. Slater GJ, et al. Is an Energy Surplus Required to Maximize Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy Associated With Resistance Training. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2019; 6: 131.

14. Jafari A, et al. Effect of Resistance Training on Appetite Regulation and Level of Related Peptidesin Sedentary Healthy Men. Medical Laboratory Journal, Jul-Aug, 2017; 11 (4): 24-29.

15. Whybrow S, et al. The effect of an incremental increase in exercise on appetite, eating behaviour and energy balance in lean men and women feeding ad libitum. British Journal of Nutrition, Nov 2006; 100 (5): 1109-1115.

16. Slater GJ, et al. Is an Energy Surplus Required to Maximize Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy Associated With Resistance Training. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2019; 6: 131.

The Mandatory “I Ain’t Your Mama, So Think For Yourself and Take Responsibility for Your Own Actions” Disclaimer: All content is provided for information and education purposes only. Individuals wishing to make changes to their dietary, lifestyle, exercise or medication regimens should do so in conjunction with a competent, knowledgeable and empathetic medical professional. Anyone who chooses to apply the information on this substack does so of their own volition and their own risk. The author/s accept no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any harm, real or imagined, from the use or dissemination of information contained on this substack. If these conditions are not agreeable to the reader, he/she is advised to leave this substack immediately.

Leave a Reply