Is it the best shoulder exercise ever, or an injury-maker to be avoided at all costs?

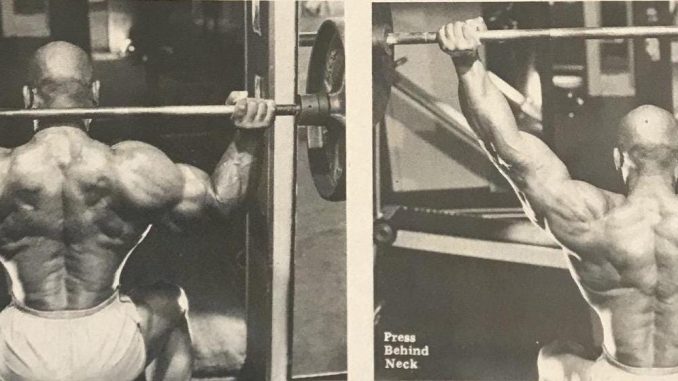

I’m old enough to have witnessed the downfall of numerous exercises that were once popular gym staples. Dumbell pullovers, upright rows, the pec deck, behind-the-neck lat pulldowns, press-behind-neck shoulder presses ... the list goes on.

The press-behind-neck (PBN) has gone from star to stigma status, but there are a number of influential lifters who won’t let it go.

Lifting personality Mike O’Hearn is a vocal defender of the PBN, and says other influencers who recommend against it are “snowflakes”.

Four-time World’s Strongest Man Zydrunas Savickas wrote in a 2017 social media post the PBN is a “good exercise” to “build strong shoulders and keep flexibility.”

Dmitriy Klokov, a former Russian Olympic weightlifter, World and European Champion, was clearly a fan of the PBN.

A 2016 article at the popular T-Nation website by Christian Thibaudeau admonishes readers “Don’t Fear the Behind the Neck Press.”

Thibaudeau claims the PBN is “the most effective pressing exercise for overall shoulder development. This is found both in the trenches and in the lab.”

Despite the “lab” reference, Thibaudeau doesn’t cite any research. I’m guessing he’s referring to EMG studies showing activation of the medial and posterior deltoids is higher during the PBN than presses launched from the front of your neck (Coratella et al, 2022).

No-one’s arguing the PBN can’t build muscle; that’s a moot question. The real conundrum is whether the movement’s benefits outweigh the risks. After all, there are other exercises that target the medial and posterior heads of the deltoid.

To address the question of safety, Thibaudeau cites the examples of Klokov, Ted Arcidi (one of the first to officially bench press 700 lb and a regular PBNer), and Paul Carter, reportedly “a monster presser” capable of 365 pounds in the PBN.

Klokov and Carter have reportedly nursed serious shoulder issues, so Thibaudeau’s argument is that if it’s safe for these guys, then how can it be an inherently dangerous exercise?

“[I]f a lifter who suffered a severe shoulder injury can do behind the neck presses with over 315 pounds, that’s a sign that if you have proper mobility it’s a not an inherently dangerous exercise.”

I’m not a fan of the “If it’s good for celebrity X, it must be good for you!” argument. Just because genetically gifted individuals can perform a movement without overt issue, doesn’t automatically mean you should attempt to emulate them.

The common admonition to only do the PBN if you have “proper mobility” is also disingenuous, because few if any general population trainees undergo mobility assessments before hitting the gym. That kind of targeted assessment is largely confined to high-level athletes and folks who have already incurred an injury or musculoskeletal complaint.

So to get some clarity on the ongoing PBN controversy, I decided to boldly venture where few others commenting on the topic seem to have gone:

The scientific literature.

There’s not a whole lot of published, peer-reviewed research on the press-behind-neck, but what I found was concerning.

To get an idea if resistance training increased the risk of anterior shoulder instability and hyperlaxity, Kolber et al (2013) recruited 159 healthy males (mean age 28 years). Of these, 123 engaged in weight training a minimum 2 days per week while 36 had no history of weight training participation.

Testing identified significantly greater anterior glenohumeral joint instability and hyperlaxity in the weight training group compared with the non-training controls.

When the researchers analysed the participants’ gym programs, those who performed behind-the-neck shoulder presses and behind-the-neck pull-downs were significantly more likely to test positive for anterior instability and hyperlaxity than those who did not.

These subjects evidently had the mobility to perform PBNs and behind-the-neck pulldowns, but it was nothing to celebrate - their shoulder joints were generally more unstable and lax in the anterior plane.

Which suggests those who claim “proper mobility” is the key to PBN mastery, and that you should stick with the movement to develop that mobility, are issuing less-than-intelligent advice.

The researchers found individuals who performed external rotator cuff strengthening were significantly less likely to evince anterior instability than those who did not.

No significant relationships were identified between anterior instability tests and the performance of flat bench, incline bench, chest flies, lateral deltoid raises above 90°, and back squats.

The last two exercises are noteworthy; abduction of the humerus beyond 90° is supposedly a danger zone for “impingement”, an alleged cause of shoulder pathology that I recently debunked here.

Folks like O’Hearn, meanwhile, point out that during back squats the arms are in a similar position to the start of the PBN. But hey, no-one’s recommending against the back squat on that basis, so calling out the PBN is stupid, he says.

It’s an irrelevant comparison, because at no point during the back squat do you attempt to press the weight from your shoulders - a move that would greatly increase the force applied to the glenohumeral joint while it is in the vulnerable abducted and externally rotated and outstretched position.

Kolber et al write:

“The ability of clinicians and strength and conditioning professionals to recognize ‘at-risk’ training patterns requires an awareness of documented injury trends and risk factors.”

It’s all well and good for online writers and YouTube influencers to belittle those who caution against the PBN, or to point to strong guys who allegedly did it for years without injury. If you take up their advice and it turns out to be ill-informed, you’ll have little recourse. Those influencers won’t have to pay your medical and rehab bills.

A trainer overseeing clients referred from therapists, or a coach responsible for high-level athletes, will not enjoy the same freedom from consequences. A track record of prescribing questionable exercises and injuring clients will likely lead to a loss of business, probably one’s job, and possible litigation.

Kolber et al note that addressing modifiable risk factors, such as the “high-five position” commonly assumed during upper extremity exercises, may serve to prevent and/or minimize symptoms resulting from anterior shoulder instability. Modification for the BTN press and pulldown is to bring the bar down to the front clavicle/upper chest area.

They also recommend individuals who participate in resistance training to incorporate targeted external rotator cuff strengthening because it may serve to mitigate risk for anterior shoulder instability.

A Shoulder-Popping Movement

Defenders of the PBN may object the Kolber et al study did not ‘prove’ the movement is harmful. It merely found an association.

So let me present you with a case study reported by Esenkaya et al (2000). It concerns a 22-year-old male who presented to the emergency department complaining of acute stiffness and pain in both shoulders. He’d come straight from the gym, where he’d been doing the seated PBN with a 50 kg load. As he was returning to the start position, he felt his shoulders were “going out of place” and lost control of the bar. He felt immediate pain and was unable to move his arms.

Radiologic examination showed bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation without fracture.

In plain English: Both his arms had popped out of their shoulder joints.

Ouch.

After a dose of IV diazepam (Valium) to quell the pain and save the doctors from a stream of profanities and loud screams, both humeral heads were manually popped back into place.

To keep them in place, the patient had to wear a bilateral body bandage for 3 weeks. He wore the bandage at all times and was seen weekly by his physicians. After the bandages were removed, the patient underwent 6 weeks of physical therapy. He discontinued weight lifting completely and had full range of motion 6 months after the injury.

All of which seems a very steep price to pay for a little extra medial deltoid development.

The patient was an accountant who, prior to the injury, had done weight training regularly for 3 years and had no history of dislocation. He lifted weights for bodybuilding but reported that the PBN was not one of his usual exercises. Why he decided to perform it on this occasion was not mentioned.

Esenkaya et al wrote:

“To improve form, avoid injury, and maximize gain from workouts, beginning weightlifters and those with shoulder instability should be counseled to use safer alternative techniques such as frontal military presses that do not allow movement posterior to the plane of the body.”

A Contrary View from Down Under

A 2014 paper by McKean and Burkett concluded:

“For participants with normal trunk stability and ideal shoulder ROM (range of motion), overhead pressing is a safe exercise (for the shoulder and spine) when performed either in-front or behind the head.”

Their conclusion was not based on longitudinal follow-up of participants performing PBN versus no-PBN. Instead, it was based on a one-time lab analysis of spine and shoulder movement dynamics while performing 3RM lifts of front and behind-neck shoulder presses.

This dynamic testing showed shoulder range of motion was “within passive ROM for all measures except external rotation for males with the behind the head technique.” (Bold emphasis added)

The authors nonchalantly added in the exception about external rotation, and a she’ll-be-right-mate recommendation to increase passive ROM before doing the PBN.

“To avoid possible injury passive ROM should be increased prior to behind the head protocol,” they wrote.

The problem with this flippant dismissal is that the external rotation dynamics of the PBN are the key issue in the PBN controversy.

The PBN took the shoulder into a more externally rotated position than the in-front technique in both genders, as expected. However the PBN for males had an average start position of 92° external rotation which was greater than the average passive ROM of 85°.

So in this study using young injury-free folks mostly in their twenties with at least 12 months overhead pressing experience, the PBN was pushing the male participants beyond their passive external rotation ROM.

In a population of newcomers, older participants and/or those with previous injuries, we’d reasonably expect to see reduced passive ROMs and hence an even greater challenge in the PBN start position.

What the male results mean over the longer term is unclear, but until such longer-term data are in, I’m not prepared to pronounce the PBN as Safe&Effective™ for everyone so long as they do some stretching.

Summary

We Homo sapiens share the same basic skeletal structure but the exact positioning and angles of our joints vary between individuals, and the glenohumeral joint is no exception (Kariminasab et al, 2022). Exactly how this affects the PBN is not known, but it may help explain why some people can do the exercise for years on end without apparent issue, while others develop shoulder instability and even end up in the ED with bilateral shoulder dislocation.

It may well be that some people are structurally suited to perform the PBN - but until a clear and strongly validated set of guidelines is developed to identify just who these people are, it’s not an exercise I recommend.

References

Coratella, G., Tornatore, G., Longo, S., Esposito, F., & Cè, E. (2022). Front vs Back and Barbell vs Machine Overhead Press: An Electromyographic Analysis and Implications For Resistance Training. Frontiers in Physiology, 13, 825880. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.825880

Esenkaya, I., Tuygun, H., & Türkmen, I. M. (2000). Bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation in a weight lifter. The Physician and sportsmedicine, 28(3), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.3810/psm.2000.03.782

Kariminasab, N., Dalili Kajan, Z., & Hajian-Tilaki, A. (2022). The Correlation Between Morphologic Characteristics of Condyle and Glenoid Fossa with Different Sagittal Patterns of Jaw Assessed by Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Turkish Journal of Orthodontics, 35(4), 268–275. https://doi.org/10.5152/TurkJOrthod.2022.21136

Kolber, M. J., Corrao, M., & Hanney, W. J. (2013). Characteristics of anterior shoulder instability and hyperlaxity in the weight-training population. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27(5), 1333–1339. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318269f776

McKean, M., & Burkett, B. J. (2015). Overhead shoulder press – In-front of the head or behind the head? Journal of Sport and Health Science, 4(3), 250-257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2013.11.007

Leave a Reply