Are 'fast'or 'slow' reps better? Are rep tempo prescriptions valid, or pseudoscientific nonsense?

One of the more bizarre phenomena I’ve come across in the world of resistance training is the arbitrary prescription of repetition speeds.

I’m not talking about commonsense prescriptions like “lift and lower the bar in a controlled manner” or “avoid throwing and bouncing the weight.”

Nor am I talking about training specifically aimed at helping athletes improve their rate of force production, using ‘explosive’ exercises like jump squats or modalities like plyometrics.

Nor am I talking about powerlifters who use sets with extended pauses at the bottom of the bench press and squat movements, to build their explosiveness “out of the hole.”

I’m talking about the folks who tell you exactly how many seconds you should spend lifting a weight, how many seconds you should spend lowering a weight, and how many seconds you should spend in between the concentric and eccentric phases of a lift.

The most common of such admonitions seems to be “take 2 seconds to lift a weight, and 4 seconds to lower it.” I’m not sure who invented the 2/4 tempo rule, but it is repeated ad nauseum in the manner of a self-evident truth.

The first time I came across a specific rep tempo recommendation was in an article by Mr Universe winner Mike Mentzer in the mid-1980s. He asserted the 2/4 rule, but when you watch footage of Mike actually training, you can see he takes nowhere near that long to complete a repetition. He uses what looks to be a far more natural, self-selected tempo. On the lateral raise machine, he even begins the movement in an explosive manner - a far cry from the snail pace required to produce a 6-second rep.

The first time I took any real interest in rep tempo was in the early 1990s, when I purchased Ellington Darden’s BIG. The book recommended “super-slow” training, where you take 10 seconds to lift a weight, and 5 seconds to lower it back down again. The cover of BIG claimed it was “The Ultimate Diet and Exercise Plan for Massive Muscles” - but it wasn’t. I talked my training partner into giving it a whirl, but after 4 weeks neither of us had made a whit of progress and we unanimously agreed the experiment had been a waste of time.

Then, in the late 1990s, along came the late Charles Poliquin. Despite his penchant for making absurd claims - or perhaps because of it - Poliquin became a popular author*. Through his articles in the now defunct Muscle Media 2000 magazine, and later the T-Nation website, he popularized the concept of prescribed rep tempos.

His 1997 book The Poliquin Principles, which alternated between giving training advice and hating on Mike Mentzer, featured an entire chapter devoted to rep tempo, as did the 2016 version.

In the latter, he claimed:

“Slow-speed lifting brings about more metabolic adaptations than high-speed lifting. Training at faster speeds does not induce these changes. Also, performing slow reps builds the connection between the mind and the muscle, and they make a great finishing-off set.”

He provided zero evidence to support these fanciful claims.

In the 1997 version, he provided two incomplete, bracketed citations to support his rep tempo claims - “Ungard (1989)” and “Doherty (1989)” - neither of which I have been able to retrieve via PubMed or web searches.

Poliquin claimed: “To achieve the appropriate training stimulus, you must adhere to the precise speed of movement for all aspects of a lift: eccentric, isometric and concentric.”

But what is “the precise speed of movement”? What does that mean, exactly? Who determines this “precise speed”? And upon what scientific or even compelling anecdotal basis do they do so?

No answer.

Lack of scientific references notwithstanding, Poliquin believed that rep speed for every exercise in a training program should be prescribed using a three-digit (1997) and later a four-digit (2016) abbreviation.

He got this idea from Ian King, a strength coach from Australia, who claims to have invented the 3-digit system.

How does it work?

Poliquin gives the example of a “4213” tempo prescription for the bench press. You take 4 seconds to lower the barbell to your chest, pause for 2 seconds when the bar makes contact with your chest, take 1 second to press the weight from your chest to lockout, then rest 3 seconds with the bar hovering above you in the lockout position before performing another repetition.

Again, why you would want a heavily loaded barbell hovering above you for an arbitrary period of 3 seconds, even as you become increasingly fatigued, was never explained.

Apart from garnering odd looks in the gym, frustrating the poor bloke who’s next in line to use the bench, and increasing your likelihood of craniofacial surgery, there is no evidence this will achieve anything a regular tempo won’t.

In the 2016 edition of his book, Poliquin gives examples of hypertrophy routines featuring a bizarre array of rep tempo prescriptions. Parallel bar dips - an exercise many folks would be best avoiding, especially those with preexisting shoulder issues - are to be performed for a “4010” tempo.

Meanwhile, “3010” is prescribed for the incline dumbbell press, “2210” for the standing calf raise, “2012” for the back extension, and “40X0” for the lying leg curl (“X” indicates the concentric portion should be performed as quickly as possible).

While clearly harboring a seething disdain for Mike Mentzer, Poliquin had no problem citing other HIT stalwarts like Arthur Jones, Ken Hutchins and Ellington Darden in support of super-slow training (Chapter 8 of TPP 2016). In the 1997 edition of TPP, he prescribed super-slow flyes and lateral raises (p. 20).

Again, Poliquin provided no scientific rationale for the specific tempos. Why a 4-second eccentric on one exercise, but a 2-second eccentric on another? Why an “X” concentric tempo for leg curls, a 10-second concentric for machine lateral raises, yet a 1-second concentric for “lean-away” lateral raises?

If you’ve ever delved into the research examining rep tempo, and the associated concept of “time under tension” (another farce I will address in due course), it’s not hard to work out the lack of explanation behind these different rep tempos.

There is no science behind them - they are entirely arbitrary.

In fact, not only does the published research indicate the rep tempo phenomenon is largely nonsense, it shows unnaturally slow tempos may in fact impede hypertrophy and strength gains.

So let’s take a look at that research.

The content below was originally paywalled.

Note: The Poliquin/King system of rep tempo abbreviation begins with the eccentric duration. Published sports scientists, in contrast, almost always cite the concentric duration first. So under the former system, a 2-second concentric/4-second eccentric tempo would be cited as 4020, which to me looks more like a Queensland zip code. Published sports scientists, in contrast, typically cite this as a 2/4 tempo. Except where noted, in the discussion that follows I use the method prevailing among sports scientists.

Self-Selected versus Prescribed Rep Speeds

Left to their own devices, most motorists will travel at a speed that is safe and appropriate for the surrounding conditions. They will travel faster on wide, flat, straight, dry roads, and slower in conditions of poor visibility and traction, even if the signs say they can legally travel 20-30 km/h faster.

In addition, there is a well-established phenomenon known as the Solomon Curve which shows the biggest danger on the roads is not the motorist who fails to obey the arbitrary posted speed limits designated by overpaid (and revenue-hungry) bureaucrats. The real danger is the motorist travelling significantly faster or slower than the mass of accompanying road users, irrespective of how fast that vehicular peleton is travelling. Your reckless wanker-in-a-hurry weaving in and out of traffic, and the car full of lawn bowlers travelling 15 km/h slower than everyone else, are the real dangers because they trigger more instances in which vehicles pass or overtake each other. Every such instance increases the likelihood of a collision involving two or more vehicles.

A 1994 paper by Brazilian sports scientists suggests that, just like sensible motorists, people with a modicum of resistance training experience are capable of self-determining an appropriate lifting speed - and are better served by doing so.

Seventy-five “moderately-trained” college-age men participating in strength classes were recruited for the study. In randomized crossover fashion, each subject was tested for the maximum number of repetitions they could achieve on the push-up and pull-up exercises, using the following tempos:

Self-selected (fast);

2-second concentric/2-second eccentric;

2-second concentric/4-second eccentric.

The exercises were performed using standardized grip widths and ranges of motion.

To ensure the desired tempo in the 2/2 and 2/4 conditions, the researchers used a digital timer and gave the subjects verbal signals.

That right there highlights the impracticality of tempo prescriptions, because achieving exact tempos in real life world require a partner wielding a timer and giving verbal signals.

Even if you could achieve this training scenario, the results indicate it would be a waste of time.

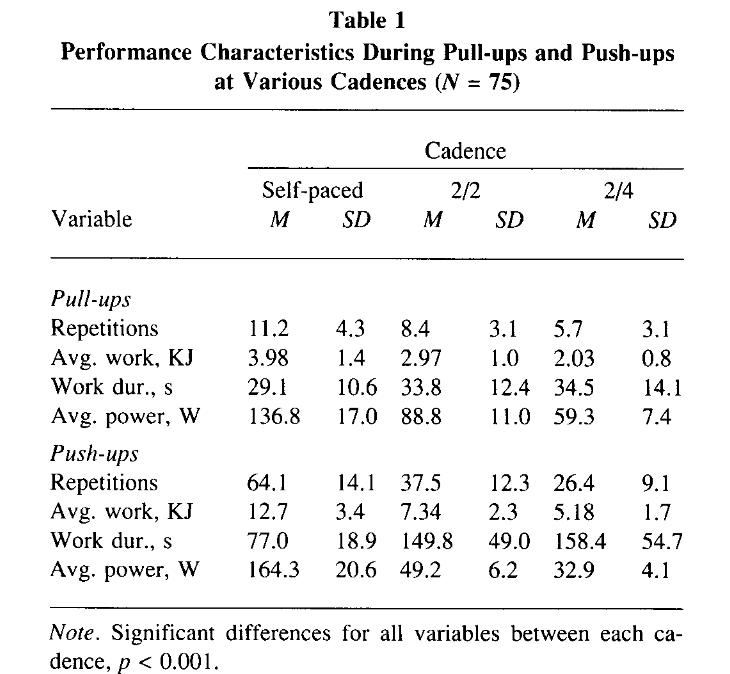

When using a self-selected tempo, the subjects averaged 11.2 reps on the pull-up, and performed 64.1 repetitions on the push-up exercise.

During the 2/4 condition, they could only average 5.7 and 26.4 reps on the pull-up and push-up, respectively.

The results for the 2/2 condition fell mid-way between the faster and slower conditions

As the following table from the paper shows, not only did a self-selected tempo allow for more reps, it allowed those extra reps to be completed in less time and with a far higher power output!

In other words, using the oft-recommended 2/4 tempo, and even a 2/2 tempo, instantly made the subjects weaker on pull-ups and push-ups.

Hatfield et al 2006 reported on nine young men, mean age 23.9, with at least 1 year of experience using both the shoulder press and squat exercises. On separate occasions and in randomized, crossover fashion, they performed both exercises on a Smith machine for as many repetitions as possible at either 60 or 80% of one-repetition maximum (1RM) using the following tempos:

Self-selected;

10-second concentric/10- second eccentric.

Subjects performed significantly fewer repetitions during the super-slow testing sessions.

When using 60% 1RM for squats, the subjects were able to average 24 reps with their self-selected tempo, but only 5 reps using super-slow.

When using 80% 1RM for squats, the subjects averaged 12 reps with self-selected tempo, but could only squeeze out 2 reps when lifting super-slowly.

Similar results were seen on the shoulder press. At 60% 1RM, the subjects averaged 14 and 4 repetitions in the self-selected and super-slow conditions, respectively. The concomitant rep count for the 80% 1RM condition was 6 and 1, respectively.

Peak force and power were also significantly higher in the self-selected tempo conditions.

The authors concluded: “The results of this study indicate that a [super-slow] velocity may not elicit appropriate levels of force, power, or volume to optimize strength and athletic performance.”

A 2018 paper by Brazilian sports scientists reported a similar result, this time using the 45° leg press exercise.

They initially recruited 16 men aged between 18 and 30 years, with an average 3.6 years of resistance-training experience. Twelve subjects completed the study.

In randomized cross-over fashion, they performed the leg press using the following tempos:

Self-selected;

2-second concentric/2-second eccentric.

During both sessions, participants performed 3 sets to failure at 80% of their 1RM, with a 1-minute rest period between sets.

For both protocols, muscle failure was defined as the inability to move the leg press platform through a 90° range of motion. Furthermore, for the prescribed tempo protocol, a set was terminated if the participant could no longer maintain the 2/2 tempo for more than 2 repetitions.

A metronome was used to help subjects maintain the required tempo during the 2/2 protocol.

During both protocols, the researchers also attached EMG electrodes to the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis muscles of the dominant thigh.

Once again, the self-selected rep tempo reigned supreme. Subjects averaged 25.5 reps during the self-selected protocol, versus 16.5 during the artificially slow 2/4 condition.

Compared to the 2/4 condition, the self-selected protocol resulted in significantly greater EMG amplitudes on all 3 sets. This indicates the faster, self-selected rep speed was recruiting significantly more motor units in the thigh muscles (a motor unit consists of one motor neuron and all the muscle fibers it stimulates).

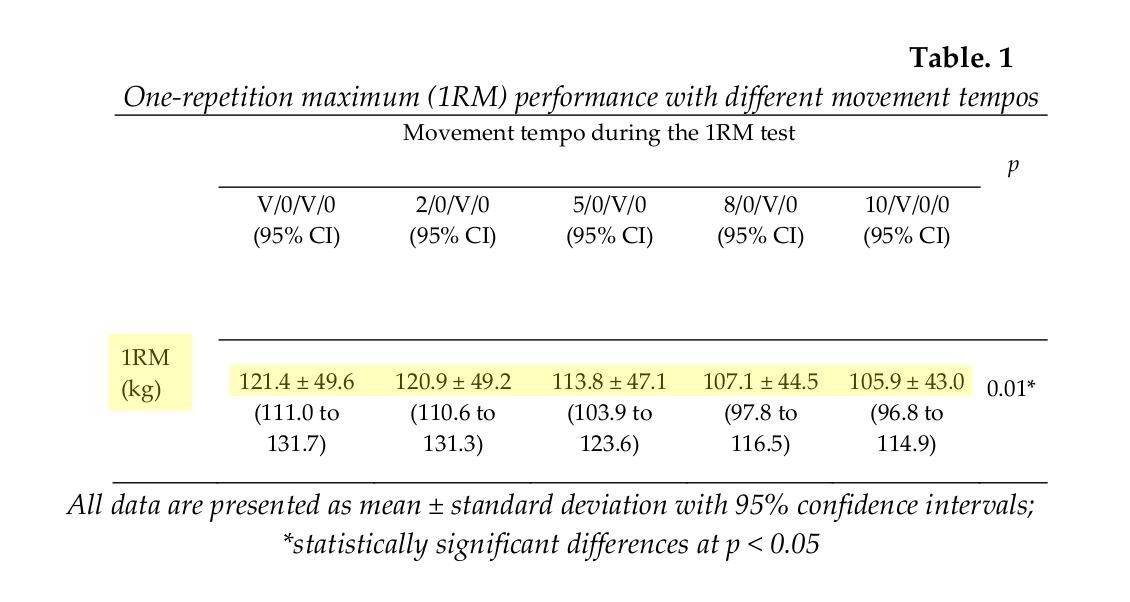

More recently, Wilk et al 2020 examined the effect of rep tempo on 1RM bench press results.

Ninety men (mean age = 25.8 years, body mass = 80.2 kg) with a minimum one year of resistance training experience took part in the study. Using a randomized crossover design, each participant completed a bench press 1RM test using five different tempos during the eccentric (lowering) phase of the movement. The tempos were cited using a Poliquin/King-style format, with “V” indicating a volitional, or self-selected, tempo:

V/0/V/0

2/0/V/0

5/0/V/0

8/0/V/0

10/0/V/0

A standardized hand placement was used, and all repetitions were performed without bouncing the barbell off the chest and without raising the lower back off the bench.

The results showed the V/0/V/0 and 2/0/V/0 protocols resulted in a significantly greater 1RM than the slower 5/0/V/0, 8/0/V/0 and 10/0/V/0 protocols.

The results are consistent. Without the interference of ‘experts’ who like to overthink and overcomplicate things, moderately experienced gymgoers will lift more weight, perform more reps and generate more power when using a voluntary tempo that naturally feels right for them.

Which means those who insist artificially slow, prescribed tempos are somehow superior to self-selected tempos must explain how protocols that consistently make people weaker despite using standardized form could possibly produce greater increases in hypertrophy and strength?

Longer Term Hypertrophy and Strength Outcomes

The aforementioned studies were short-term endeavors. Does retarding your performance in the short-term somehow, magically, lead to enhanced strength and hypertrophy over the longer term?

Schoenfeld et al 2015 was a review that looked at the effect of rep speed on hypertrophy outcomes. After reviewing eight intervention studies lasting 6-14 weeks, they found hypertrophy outcomes were similar when training with repetition durations ranging from 0.5 to 8 seconds to concentric muscular failure.

However, none of the eight studies allowed for self-selected tempos; all the tempos were prescribed.

Schoenfeld et al also added, contrary to claims by Poliquin and others, that it was not clear if combining different repetition tempos would enhance the hypertrophic response to resistance training. “This possibility requires further study,” they noted.

As for strength gains, the answer should be obvious to anyone familiar with Olympic lifting - an activity where explosive lifting allows small Chinese women to clean and jerk weights that a lot of Western males would struggle to deadlift.

Yes, the research indicates faster tempos produce superior results.

Jones et al 1999 reported on a group of collegiate NCAA Division 1AA football players who were assigned to one of 2 groups.

The experimental group performed the concentric phase of all upper-body exercises with maximal acceleration, while the control group members performed the concentric portion with the same tempo they normally used in their training.

After 14 weeks, the experimental group increased significantly more than the control group in both the 1RM bench press (+9.8 vs +5.0 kg) and in the seated medicine ball throw for distance.

The subjects were also tested while performing a plyometric push-up on a force plate. Increase in average power output was over 3 times as great in the experimental group, while decrease in amortization time (the time between the hands landing on the platform and then leaving the platform) was over 2 times as great with the experimental group. However, neither of these results attained statistical significance.

González-Badillo 2014 compared the strength gains of high-speed and slower-speed training among physically active male sport science students with 2–4 years of recreational weight training experience.

The subjects were divided into two groups. Both groups followed the same routine, performing the Smith machine bench press three times weekly, and using progressively heavier %1RM weights over the 6 week study. One group performed all repetitions at the maximal intended concentric velocity associated with the %1RM intended for the respective session. The other group intentionally lifted the weight at half the target maximal velocity. The eccentric phases of each repetition were performed at a controlled velocity in both groups.

After six weeks, the maximal velocity group increased their 1RM on the Smith machine bench press by 12.4 kg (18.2%), compared to 6.9 kg (+9.7%) in the reduced velocity group.

The Super Way to Slow Down Your Gains

Let’s take a closer look at super-slow training, where the recommended tempo for a concentric contraction is 10 seconds - and sometimes more.

Fans of this style of training are fond of citing two non-randomized studies by Wayne Wescott and colleagues.

Those studies are reported in Westcott et al 2001.

All up, 147 untrained men and women (mean age = 53.6) trained 2-3 times per week for 8-10 weeks on a 13-exercise Nautilus circuit performing one set of each exercise. The researchers report around 10 percent of subjects dropped out and there were no injuries during the study.

The subjects trained using one of two tempos. What the researchers called “regular speed repetitions” in fact were prescribed tempo reps comprised of a 2 second concentric, 1 second pause, and 4 second eccentric. This group performed 8-12 reps per set.

The other group followed a super-slow protocol using a 10 second concentric and 4 second eccentric. This group performed 4-6 reps per set.

In Study 1, the subjects were tested for “strength” at weeks 2 and 8 on all 13 exercises, while in Study 2, only bench press “strength” was tested at weeks 2 and 10.

The researchers claimed “In both studies, Super-Slow training resulted in about a 50% greater increase in strength” than “regular speed training”.

They further claim “In Study 1, the Super-Slow training group showed a mean increase of 12.0 kg and the regular speed group showed an increase of 8.0 kg increase. In Study 2, the Super-Slow training group showed a 10.9 kg increase and the regular speed group showed an increase of 7.1 kg.”

The “regular speed training” was of course nothing of the sort. Just like the super-slow protocol, it featured an unnaturally slow and prescribed tempo.

Nonetheless, the results still go against what we learned above, where strength gains seem to decrease as the prescribed duration of tempo increases.

The explanation for this seeming anomaly becomes obvious when you read the study’s methods. When the subjects were tested for “strength” at weeks 2 and 8-10, the 2/1/4 group was tested for improvement in their 10RM, while the super-slow group were tested on their 5RM.

So a different rep target was used in each group. But that’s hardly the end of it.

During testing, both groups used the same rep tempo that featured in their training protocol.

Read that again.

Westcott et al did not subject both groups to the same tests performed in “real life” conditions, like completing a 1RM on the bench or leg press in good form at a self-selected tempo. Instead, the subjects performed their RM tests with either a 2/4 or 10/4 tempo. The results do not show the super-slow group made greater strength gains. They simply show that the super-slow group got relatively stronger at lifting at an unnatural 10/4 tempo than the other group did at lifting weights with an unnatural 2/4 tempo. And that’s using different RM targets for each group, which is hardly good science.

What would have happened if the subjects were tested before and after using the same RM target and using the same natural, self-selected speed?

Keeler et al 2001 was published the very same year as Westcott et al 2001, yet you’ll rarely see it cited by super-slow advocates. I submit the reason is because this higher quality study found significantly lower strength gains in the super-slow group.

Fourteen healthy, sedentary women, 19–45 years of age, were randomized to either the super-slow or “traditional” rep tempos. The former consisted of 10-second concentric and 5-second eccentric contractions. The “traditional” tempo was in fact a 2/4 protocol.

Irrespective of tempo assignment, both groups trained 3 days per week on a whole-body routine using eight Nautilus machines.

Both groups performed each exercise for one set of 8–12 repetitions to muscular failure. The 2/4 group began each exercise using 80% of 1RM, while the SS group used approximately 50% of 1RM. The researchers noted: “It is recommended that for the SS group the weight is reduced about 30% from what is normally used.” This because you simply cannot use the same amount of weight when you train like a slow motion mime artist instead of a strength athlete.

After ten weeks, both groups increased their 1RM strength significantly on all 8 exercises. However, the 2/4 group’s improvement in total weight lifted was significantly greater than that of the SS group (39% vs 15%).

The 2/4 group increased significantly more than the SS group on bench press (34% vs 11%), lat pulldown (27% vs 12%), leg press (33% vs 7%), leg extension (56% vs 24%), and leg curl (40% vs 15%).

No significant differences were found for body composition, exercise duration on a cycle ergometer, or other aerobic variables.

Neils 2005 reported on sixteen male and female subjects, between 18-30, who participated in an 8-week resistance training program using either a 10/5 super-slow or 2/4 tempo. Both groups trained 3 days per week, performing the bench press, bicep curl, triceps extension, leg extension, leg curl, squat, and upright row.

The 2/4 and 10/5 groups improved 1RM strength by 6.8% and 3.6% in the squat exercise and 8.6% and 9.1% in the bench press, respectively.

Peak power for the counter movement jump increased significantly in the 2/4 group, from 23.0 W/kg to 25.0 W/kg; no such increase was seen in the super-slow group.

No changes in body composition were seen for either group.

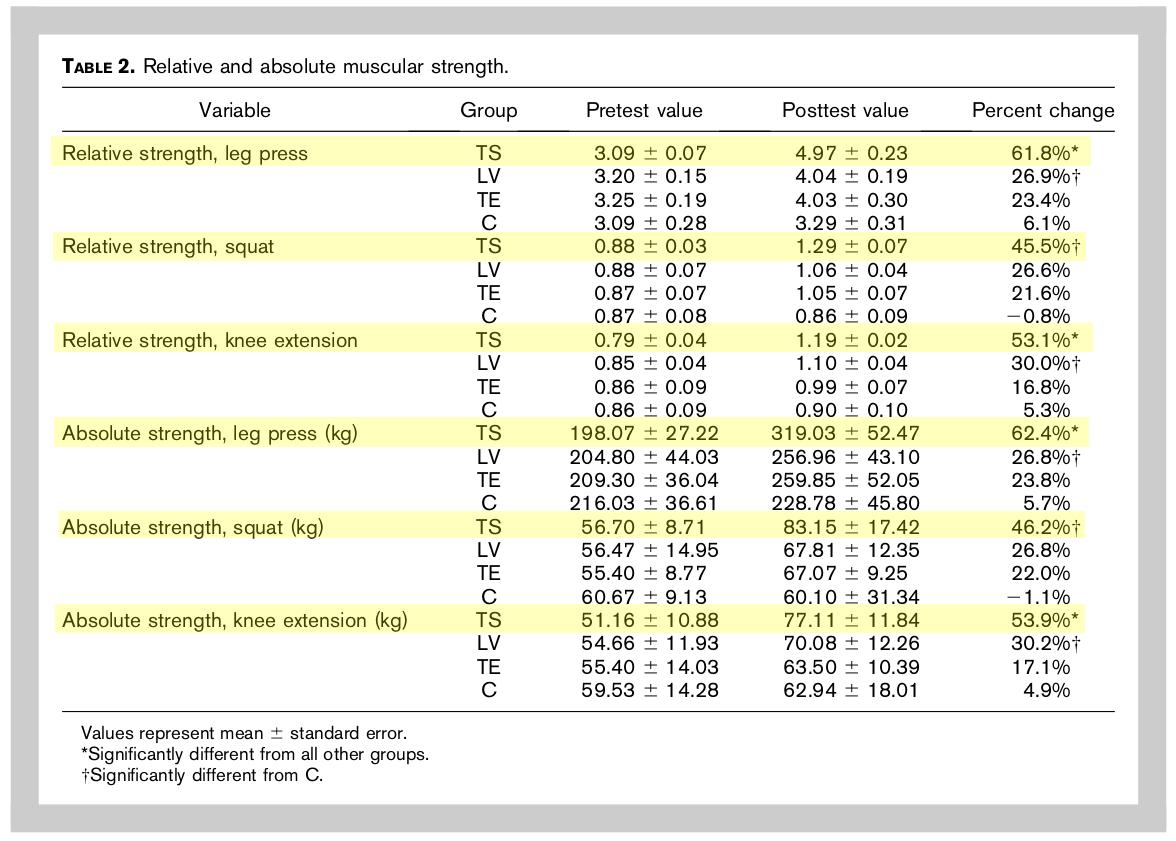

In Rana 2008, thirty-four healthy but untrained females (mean age 21.1 years) were randomly divided into 4 groups. One group served as a control, while subjects in the remaining groups all trained their lower body 16-17 times over 6 weeks, using different tempos.

At each workout, the 3 training groups performed 3 sets each of leg press, knee extension, and Smith machine squats.

The three different tempo protocols were as follows:

1–2 second concentric/1–2 second eccentric, using 6–10 RM (“Traditional Strength” training);

1–2 second concentric/1–2 second eccentric, using 20–30 RM (“Traditional Endurance” training);

10 second concentric/4 second eccentric, using 6–10 RM (“Low Velocity” training).

After six weeks, the “Traditional Strength” training produced far greater increases in both absolute and relative strength (the former refers to the total amount of weight you can lift, the latter refers to how much you can lift in relation to your body weight).

Meanwhile, the “Traditional Endurance” training produced the greatest increase in number of reps performed using 60% of 1RM.

None of the groups experienced any significant changes in body weight, fat mass or lean mass. However, the researchers also obtained muscle biopsy samples from 31 of the 34 subjects, as reported in Schuenke 2012. Only the “Traditional Strength” group saw an increase in type IIA fast-twitch muscle fibers, underscoring why faster tempos with heavier weights are superior both for strength development and conditioning for sport activities requiring rapid force production.

Kim 2011 compared training with a 10/10 tempo at 50% 1RM with a 2/2 tempo at 80% 1RM. I won’t spend too long on this study as it introduced other variables aside from tempo. The super-slow group trained twice per week using 1 set per exercise, while the 2/2 group trained twice per week using 3 sets per exercise.

The researchers did this to equalize the amount of training time per week between groups, based upon the “time under tension” charade where everyone seems to focus on time and forgets about the crucial tension aspect of the equation.

In effect, the researchers introduced two additional confounding variables into the study: Volume and frequency. As all the female subjects were untrained, training more often with more sets could possibly have accelerated strength gains via an enhanced learning effect.

After 4 weeks, only the 2/2 group experienced statistically significant increases in 1RM when compared to a non-training control group.

Carlson et al 2018 reported on fifty-nine physically active male and female participants, with at least 6 months’ experience at a Minnesota gym using single set to failure training.

The subjects were randomized to one of 3 groups;

2 second concentric/4 second eccentric;

10 second concentric/10 second eccentric;

30 second eccentric/30 second concentric/30 second eccentric.

During the ten-week intervention, the participants trained in supervised 1-on-1 sessions, twice weekly. All exercises were performed using Nautlius, MedX and Hammer Strength machines.

A single set of each exercise was performed. The 2/4 group aimed for between 8-12 repetitions; the 10/10 group 3-5 repetitions; and the 30/30/30 group 1.5 repetitions.

No differences in hypertrophy or body composition were detected. This is hardly surprising, because the subjects were not instructed to consume a calorie excess (a prerequisite for muscular weight gain). Meanwhile, little fat loss is to be expected from such a low-volume routine performed only twice-weekly.

As for strength gains, the authors report similar increases in pre- and post-intervention “predicted” 1RM for all three groups, which contradicts everything we’ve observed so far. I suspect the reason for this anomalous result has a lot to do with the method of 1RM testing. Or more precisely, the complete lack of it.

At no point did any of the subjects perform an actual 1RM.

Instead, the subjects’ 1RM was estimated using their 10RM. Or at least, that was the plan.

Explaining their methods, the authors write:

“It was not considered essential that an exact 10RM load was identified, just that a load permitting failure between 7-10 repetitions was (for both pre and post testing this resulted in a mean of ~7 repetitions). This was because this test was then used to predict 1RM using the Brzycki (1993) equation (predicted 1RM = load lifted / (1.0278 – (0.0278 x number of repetitions)) which has been shown to have a very high correlation to actual 1RM.”

Ugh.

Let’s break down all that gobbledegook. The “estimated 10 repetition maximum (RM) from which 1RM was predicted” was in reality a 7RM. That 7RM was then used to ‘predict’ a 1RM that the subjects never performed, and therefore was never validated.

The authors say this doesn’t matter, because the Brzycki formula has a high correlation to actual 1RM.

But does it?

The sole study they cite in support of this claim (Nascimento et al 2007) compared the Brzycki formula and actual 1RM for only one exercise: The barbell bench press, performed in a supine position with free weights. Carlson et al, however, used three entirely different exercises to estimate 1RM: The Nautilus Evo seated chest press, MedX Avenger leg-press, and MedX pull-down machines.

LeSuer 1997 examined seven 1RM equations, and found most produced significant differences from actual 1RM in the bench press and squat, and all significantly underestimated 1RM deadlift.

In the bench press, the Brzycki equation underestimated actual 1RM by a mean 5.4 lb, with a standard deviation of 7.6 lbs around this mean figure.

In the squat, the mean difference was 10.7 lb with an 18.8 lb deviation. In the deadlift, the Brzycki formula underestimated 1RM by 29.1 lb with a 26.8 lb standard deviation.

Gonzalez-Rave 2021 used the Brzycki equation to estimate 1RM from the 3RM bench press and half-squat lifts of 46 male and 15 female sport sciences undergraduates. The narrower gap between 3RM and 1RM would be expected to increase accuracy, but the researchers still observed mean differences of 9.3 (±11.1) kg and 4.6 (±6.2) kg in the half-squat and bench press.

The bottom line is that 1RM equations can give a ballpark estimate of someone’s 1RM, but they are no substitute for actually performing a 1RM. In scientific studies, precision is paramount, and ballpark estimates hardly qualify as precise.

One other observation is worth noting here: Carlson et al are clearly amenable to single-set training. So am I, but I nonetheless consider super-slow training to be a load of cobblers. There is, however, a segment in the “HIT” (single set to failure training) camp highly amenable to the super-slow philosophy. Indeed, it was HIT proponent Ellington Darden who was instrumental in popularizing super-slow training.

The possibility of a preexisting bias towards super-slow ideology, the less-than-optimal methodology of this study, and the fact other researchers have not replicated its results lead me to regard its findings with the utmost skepticism.

Conclusion

Certain ‘experts’ have made lavish claims for artificially slow lifting tempos, but routinely fail to cite scientific evidence supporting their recommendations.

Because there is none.

There is currently no evidence that artificially slow lifting tempos offer any strength or hypertrophy advantages over self-selected lifting speeds. To the contrary, the available data indicates that strength gains diminish with increasing rep duration.

You are not as dumb in the gym as the ‘gurus’ would have you believe. In fact, it is their bizarre tempo recommendations that, when held up to the bright light of scientific scrutiny, come off as utterly daft.

The important thing when lifting a weight is that you feel safe and in control, and you don’t need to engage in a bizarre slo-mo mime act to achieve that. The research indicates that good form and a self-selected tempo are the optimal combination in the gym.

*Poliquin once famously claimed he gained 14.5 lbs. of solid muscle whilst simultaneously losing 3.5 lbs. of fat, in only five days. That's extremely unlikely even on steroids, but Poliquin claimed he achieved this other-worldly muscle gain simply by visiting the Dominican Republic and eating the local food there.

"Eating avocados (in the US),” he wrote, “is like eating fiberglass once you've had a DR avocado. It's like having sex with Pamela Anderson then having to have sex with Rosie O'Donnell."

Sure.

In 2009, Poliquin claimed he once trained “a first-round pick for the NFL. He put on 29 lbs of lean body mass in one month once I jacked his fish oil intake to 45 grams a day. If you want to put muscle on and lose fat, take at least 30 grams of fish oil a day.”

Rest assured, if someone gained 29 lbs of lean mass in one month, they sure as heck didn’t do it by taking fish oil.

But hey, if you get off on nosebleeds and soiling your pants while squatting, then 30-45 grams of fish oil a day will probably rock your world.

In 2007, Poliquin posted a since-removed YouTube video in which he appeared drunk. According to the slurring Canadian expat, if you believed in calorie-counting you were "a certified moron". It was quite the spectacle to watch a guy struggling to deliver a coherent sentence simultaneously accusing others of suffering cognitive impairment.

“When people ask about diet tips,” said Poliquin, “I tell them to try the meat & nuts breakfast. Nothing is better for maximizing energy and mental focus.”

Poliquin passed away in 2018 at the age of 57.

Leave a Reply