What the research shows about the latest lifting craze.

For the longest time, prevailing wisdom has held that resistance exercises should be performed through their full range of motion. Short choppy movements were seen as cheating, while lifting ungodly weights in the top few inches of a movement was seen as a misguided ego-boosting endeavor.

Every now and then, of course, the prevailing wisdom is challenged. If you read or watch even a smattering of online training content, you'll have noticed that “lengthened” partials are currently the hot topic in the world of weight training.

When lengthened partials first became a thing, proponents were claiming they would accelerate muscle growth when compared to full range of motion training. More recently, the gushing claims have been tempered somewhat. Currently, the reigning consensus among commentators is that research shows lengthened partials are at least equal to, and in some cases superior to full ROM training.

But is that even true?

The content below was originally paywalled.

Before I dissect that research, let's clear up some terminology.

In years gone by, partial training invariably meant performing an exercise only in the strongest portion of the movement.

While there are exceptions, you're generally stronger in the final phase of a free weight exercise than at the start. This is true for movements like the squat, bench, leg press and overhead press.

Furthermore, most exercises have a "sticking point" where your limbs are at their most disadvantageous position in terms of leverage. Once you grind through that sticking point, the movement suddenly becomes a whole lot easier as your limbs transition to a position of greater leverage.

If you take a set to complete failure, it's often at the sticking point where the set breaks down. If someone is spotting you, their assistance is most often required to get you through that sticking point.

Let's look at two common exercises as examples: The bench press and the parallel squat.

Unless you're wearing a lifting suit (which most people don't, and which dramatically changes the dynamics of the movement), then the sticking point usually occurs somewhere between a few inches from the start to around halfway through the movement.

For years, those who subscribed to partial training focused on the strongest position, that final several inches after the sticking point, because this allowed for the use of heavier weights than the full ROM. The theory, of course, being that heavier weights would equate to greater strength and hypertrophy gains.

Researchers now refer to repetitions performed in this manner as "shortened partials." They are performed in the final phase as the muscle approaches full contraction, hence the "shortened" tag.

During my mid-twenties, a program called "Power Factor Training" was being aggressively promoted in the muscle magazines, which were the primary pre-internet medium for dissemination of training bullshit 'information.' The program promised superior results from a brief routine based entirely on lifting heavy weights in the final, strongest phase of a movement.

Intrigued, and lured by the promise of superior results in less time, I purchased the book and gave the program a whirl. I've always preferred to train with a minimum of assistance gear, but in order to push the dramatically heavier weights on pressing exercises, I had to begin wrapping my wrists. Three times per week, the gym's resident ‘roid heads snorted and hmmmphed in disapproval as I monopolized the power rack. Three times per week, I dutifully pushed inordinately heavy weights through inordinately truncated ROMs, drawing strange glances from fellow trainees unaware of the "amazing!" results to be had from Power Factor Training.

After several weeks, the results were indeed amazing. Despite busting my ass, skirting on the edge of tendon strength, and lifting bone-bending weights, I had made zero progress. I hadn't gained a whit of muscle, and when I went back to full ROM training I was no stronger.

Apart from garnering strange looks in the gym, shortened partial training achieved nothing for me.

Thanks to research that has since been published, we now know why. Research reliably shows that when shortened partial training goes head-to-head with full ROM training, it comes off second best. Full ROM produces superior effects on muscle strength and hypertrophy[1].

So shortened partials are inferior to full ROM training. But what about lengthened partials?

Unlike shortened partials, lengthened partials are performed in the initial concentric phase of a weight training movement. This is the phase of a movement where the prime mover muscle is at its most "stretched" or elongated position, hence the "lengthened" designation.

Again using the bench press as an example, a lengthened partial would involve pressing the bar off your chest, stopping before or around halfway through the movement, then lowering the bar back to your chest. At the bottom of the bench press, your pectorals are in an elongated, "stretched" and “lengthened” position; at the top of the movement, they are in a contracted or "shortened" position.

The Research

Of the six studies comparing lengthened with shortened partials, five have reported superior hypertrophy results for the former[2-7]. That tells us lengthened partials don’t suck like shortened partials do, but the real question is how lengthened partials compare to full ROM training.

So let's look at the studies that directly compared lengthened partial with full ROM training.

Pedrosa et al 2021

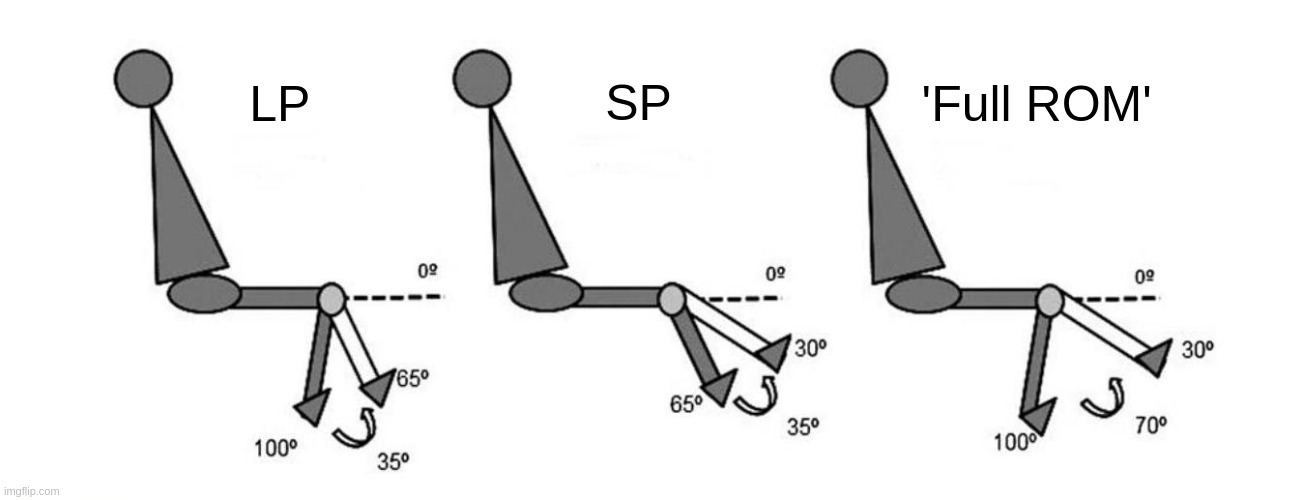

Forty-five non-trained women with a mean age of 22.7 years participated in this Brazilian study[8]. They were divided into five groups and instructed to perform the leg extension exercise using either full ROM, LP, SP or a combination routine where they alternately used LP and SP. A fifth group of subjects served as controls.

At the start of the leg extension exercise, your lower legs are hanging downwards and slightly past 90°. From this position (100° angle to be exact), the LP group performed only the first 35° of the movement.

The full ROM group, it turns out, didn't actually perform a full ROM. Their lower leg traveled from 100° to 30° short of parallel, at which point they lowered the weight again.

The shortened partial group performed the phase of the movement that spans from 65° to 30°.

If the above has your head spinning, here’s a diagram to make things clearer.

Hypertrophy was measured by ultrasound-detected changes in muscle thickness at at 40%, 50%, 60%, and 70% distal of femur length (100% distal being the end of the femur furthest from the hip).

At the 50% and 60% locations, the LP and combination groups showed a greater percentage increase in both rectus femoris and vastus lateralis thickness.

At 70% distal, the LP group showed a greater increase.

Strength changes were measured by performing 1RM tests through each of the three ranges of motion.

The LP and combination groups experienced the greatest increase in strength at the lengthened phase, while the SP group experienced the greatest 1RM increase at the final shortened phase.

For full range of motion, the greatest 1RM increases occurred in the LP, mixed and full ROM groups.

Kassiano et al 2023

In this study, also from Brazil, forty-two young untrained women performed a calf training program for 8 weeks, 3 days per week[9]. The calf raise exercise was performed in a pin-loaded, horizontal leg-press machine, for 3 sets of 15–20RM. The subjects were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups -

Full ROM (ankle ROM: -25° to +25°)

LP (ankle: -25° to 0°)

SP (ankle: 0° to +25°)

- where 0° was defined as an angle of 90° of the foot with the tibia.

The muscle thickness measurements of medial and lateral gastrocnemius were taken by ultrasound (the gastrocnemius is the muscle that gives well-developed calves their diamond shape).

The LP group experienced greater increases in medial gastrocnemius thickness than full ROM and SP groups (+15.2%, +6.7% and +3.4%, respectively).

The LP group also experienced greater increases in lateral gastrocnemius thickness (LP +14.9%, full ROM +7.3%, SP +6.2%), although the difference between LP and full ROM did not reach statistical significance.

Strength changes were not assessed, or at least not mentioned in the paper.

The above two studies involved untrained female subjects. The next two studies involved recreational weight trainees.

Goto et al 2019

Goto et al compared the effect of lying triceps extensions in LP versus full ROM fashion, performed 3 times a week for 8 weeks[10]. The subjects were forty-four male university students students aged 20–22 years. To qualify for the study they had to have at least one year of resistance training experience, be participating in a resistance training program at least 3 days a week, and performing triceps brachii exercises at least once a week.

Apart from age, height and weight (mean 64 kg), we are presented with no other baseline data, so we don't know the actual mean training experience or strength levels of the subjects.

After 8 weeks, cross-sectional area of the triceps brachii (measured in a single location via ultrasound) increased by a mean 48.7% and 28.2% in the LP and full ROM groups, respectively.

Strength increases were measured via an isokinetic dynamometer, which is of questionable relevance to those who measure their strength progress in terms of being able to lift heavier weight on an exercise. Isometric strength reportedly increased to a greater degree in the LP group, while there was no significant difference between groups in isokinetic strength at 120° per second and at 200° per second.

Werkhausen et al 2023

Werkhausen et al compared LP against full ROM using fifteen males (n=10) and females (n=5) with a mean age of 25 years, height 176 cm, and baseline body mass of 72 kg[11]. We are told the subjects had engaged in recreational weight-training, but no further information is provided regarding their training experience or strength levels.

The training consisted of unilateral, explosive leg press training three times per week, for ten weeks. Subjects trained both legs in a 45° leg press machine with a starting knee joint angle of 90°. However, for each subject, one leg was randomly assigned to exercise with lengthened partials and the other leg with full ROM.

The lengthened partials were very short movements, involving a 9° change in knee angle.

Furthermore, the eccentric phase of the lift was excluded, meaning subjects performed only the concentric phase - which, again, is not how most people train.

The researchers reported "the results indicate that the partial ROM explosive protocol does not yield inferior adaptations to full ROM in knee extensor muscle function and structure," which is another way of saying no meaningful differences in torque or power outcomes were detected between groups, and that neither protocol had any noteworthy effect on muscle thickness.

So far, we have four studies, three of which reported superior results for LP training.

Up until recently, this was pretty much the entire volume of research directly comparing LP and full ROM training. While evidently enough for some folks to get hyper-excited, it leaves this jaded veteran of the iron game rather underwhelmed.

The training routine in all of these studies consisted of a single exercise for a single muscle group, which bears little relevance to what most of us do in the gym.

Two of the studies were conducted in untrained subjects, so we don't know whether we're observing a superior effect of LP itself or simply an artifact of inexperienced subjects being able to master the initial range of motion quicker than the full and final ranges of motion (on the leg extension and calf raise movements, the initial phase constitutes a stronger, smoother and less awkward motion than the final phase).

The increase in triceps cross-sectional area detected in Goto et al was ascertained from a single site, not multiple sites. The strength results were inconsistent and their relevance unclear to someone who trains with free weights.

Werkhausen et al were the only researchers to use a compound exercise in their study (the 45° leg press), and they found no difference between LP and full ROM. However, the LP range of motion used in this study was extremely short, and subjects performed only the concentric portion of the movement.

Based on the above research, would I excitedly post a YouTube video declaring lengthened partials are the dog's bollocks and that they now comprise the bulk of my training?

Hardly.

The Latest Study - Wolf et al 2024

Just over a week ago, a group of researchers posted a preprint reporting on the results of a more relevant LP versus full ROM study[12]. Some of the authors - Brad Schoenfeld, Milo Wolf, Jeff Nippard - may be familiar to those of you who consume a lot of strength-related Internet content.

Here's what they did.

Thirty adult subjects were recruited to undergo an eight-week intervention. The participants' upper limbs were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions: A full ROM or lengthened partial regimen.

In other words, every participant performed each exercise in unilateral fashion, one side at a time. One limb traveled through the full range of motion, the other traveled through the lengthened partial phase only.

The advantage of this design is that both LP and full ROM were being tested on the same individual. This ‘within-participant’ design thus alleviates the effect of any baseline differences between groups or the potential for outlier subjects to sway the results for a group.

Five participants dropped out over the course of the study, resulting in a final sample of 25 subjects (19 males, 6 females) with a mean training experience of 4.9 years.

The upper body routines were performed twice per week. Unlike the previous studies which utilized a single exercise for a single muscle grouping, the routines utilized four exercises per session, one each for chest, upper back, biceps and triceps. Four sets of each exercise were performed at every session; the 5-10 rep range and 10-15 rep ranges were each used once weekly for each muscle grouping.

To ensure the research staff provided standardized instructions to participants, videos were shown to both the research staff and participants, displaying the appropriate ROM and technique for each exercise.

Participants were instructed to perform all sets to momentary muscular failure, with research assistants providing verbal encouragement and monitoring adherence to the prescribed ROM. At least one research assistant supervised each participant while performing the a workout.

Participants were instructed not to perform any additional upper-body resistance training outside of the study but were permitted to perform lower-body training and other physical activities at their discretion.

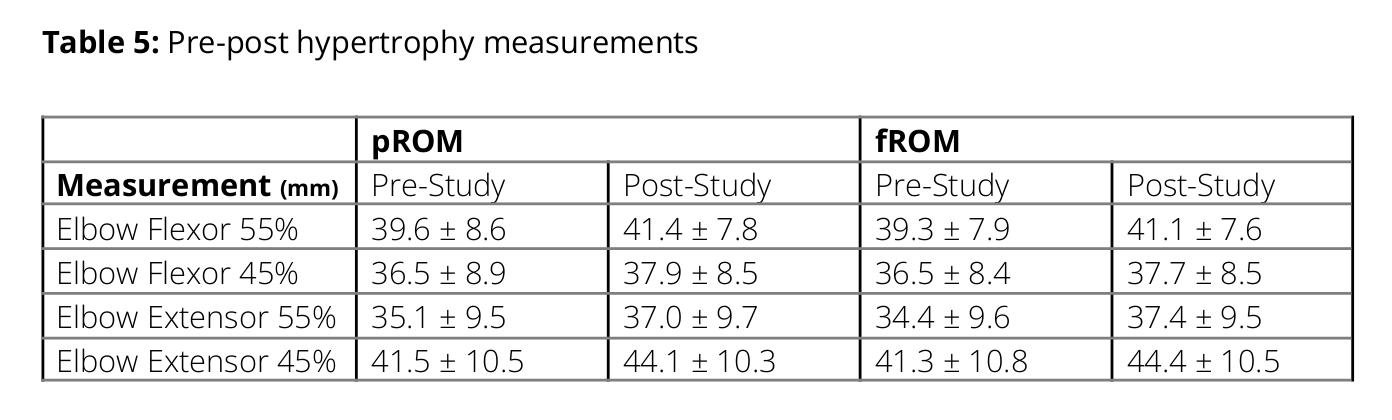

Changes in muscle thickness of the elbow flexors and elbow extensors were evaluated using ultrasound at 45% and 55% of humeral length.

Muscle strength-endurance was assessed using a 10RM test on the lat pulldown exercise, both with a lengthened partial and full ROM.

So what happened?

As this table from the pre-print shows, changes in muscle thickness were near-identical in both groups.

Near-identical results were also obtained in the 10RM full and partial ROM tests.

This study is easily the most relevant of all the LP vs full ROM studies conducted so far. Subjects with greater training experience were targeted during recruitment, helping to rule out the confounding effect of inexperience. The participants performed a multi-exercise routine, twice a week, with sets performed to failure.

And after eight weeks, both routines produced similar results.

This presents us with something of a glass half full versus half empty scenario.

The bad news is that, in the most realistic and relevant study to date, lengthened partials did not produce superior results to full ROM training. LP training is not the greatest thing since the first Ramones album; that honor still goes to the second Ramones album.

The good news is that, unlike shortened partial training, the research so far suggests LP training is similarly effective to full ROM training.

So if you really enjoy lengthened partial training, then it would seem there is little reason to stop.

What Happens When You Do Both Full ROM and LP?

If, like me, you view a work set like a juicy, freshly-picked lemon - something to be squeezed for all it's worth - then you're probably wondering what would happen if you did a full ROM set to failure, then kept going beyond failure with LPs?

This very question was recently examined by Larsen et al[13].

In this study, the participants trained unilateral standing Smith machine calf raises twice per week for 3-4 sets. Again, a within-participant design was used, with each participant training one limb to failure, and training the other limb beyond failure by performing LPs to failure once no more full ROM reps could be performed.

Before and after the ten-week training intervention, ultrasound images were taken at the most prominent and thickest site of the gastrocnemius.

No strength tests were reported.

After the intervention, ultrasound-measured muscle thickness of the medial gastrocnemius increased by 1.9 mm (9.6%) in the beyond-failure group, compared to 1.4 mm (6.7%) in the group that went to failure in full ROM only.

The study had its limitations. The subjects were untrained. No other resistance exercises were performed, so we don't know if the same results would have occurred with other muscle groups.

In fact, all the studies discussed above had notable limitations that other commentators don't seem fussed by. I'm not attacking the researchers who performed the studies - unlike research that supports Big Pharma, government and globalist agendas, there isn't a whole lot of money available for resistance training research. Through no fault of their own, sports researchers typically have to make do with limited funds and resources.

That, of course, doesn't mean we blissfully ignore the shortcomings of their studies.

As you will have noticed, where muscle hypertrophy was assessed in the above studies, the proxy measurement was usually muscle thickness measured by ultrasound. Ultrasonography is popular with researchers because it is relatively quick, inexpensive, and non-invasive.

However, ultrasound only captures measurements at the site where the transducer is placed. Vigotsky et al found wide within-individual variation in muscle thickness changes at 30%, 50% and 70% of the biceps brachii after eight weeks of training[14]. Meaning that ultrasound-detected changes in muscle thickness may not accurately reflect total hypertrophy of the muscle in question, especially when measurements are taken at a single location on that muscle.

Additionally, ultrasound is highly dependent on the skill of the operator, as differences in the pressure exerted by the transducer against the skin can result in substantial variations in measurements and thus high inter-rater error rates.

So in the beyond-failure study we just discussed, it's difficult to know what to make of a study that detected a 0.5 mm difference in muscle thickness at a single site on the medial gastrocnemius after 10 weeks of training.

Another issue with these studies is one that plagues hypertrophy studies in general: Nutrition. Muscle hypertrophy is best achieved under conditions of a calorie surplus. In fact, for leaner individuals looking to gain muscular body weight, a calorie surplus is not an option but a fundamental requisite.

Yet none of the studies instructed the subjects to consume a calorie surplus. Where nutrition was mentioned, it was to relay that subjects were told to continue eating their usual diet. In the beyond-failure study by Larsen et al, subjects were recommended to consume a daily protein intake of at least 1.6 gram per kg of body mass, but to otherwise continue with their regular eating habits.

Did the instruction for subjects to simply keep eating as usual blunt any possible hypertrophy advantage of LP or full ROM? We'll never know until the relevant research incorporating hypercaloric intakes is performed.

In Summary

The research on lengthened partials is still young, and to date has mostly involved untrained or relatively inexperienced subjects performing a single exercise for a single bodypart.

Which, of course, is not how most people train. Nor should they, because no-one is going to transform their body by doing nothing but unilateral leg extensions three times per week.

None of the studies compared complete (upper and lower body) LP and full ROM routines, and none examined the comparative impact of these modalities on overall lean mass gain. A handful of studies examined improvements in 1RM or 10RM strength, but only on a single exercise (leg press, leg extension or lat pulldown).

At the end of the day, the average gym trainee seeking to get bigger and stronger wants to know if training a certain way will accelerate muscle growth and the ability to lift more weight - not on largely useless movements like the leg extension, but on movements that matter, such as squatting, pulling and pressing movements.

The research comparing lengthened partials with full ROM training still leaves a lot of questions unanswered. Based on the research thus far, there is little to suggest LP training is superior to full ROM training. The most relevant study to date suggests the two modalities produce similar increases in upper body hypertrophy and 10RM strength in trained subjects instructed to maintain their usual eating habits.

Based on these results, I suspect the buzz over lengthened partial training will gradually die down. What we'll be left with is another option for adding variety to workouts, modifying an exercise due to injury limitations, or pushing a set past failure.

As a personal example, I certainly won't be abandoning full ROM training for LP training. However, I have begun to implement it in two ways.

Due to an impingement issue with my LHS shoulder, I haven't performed an overhead press for around fourteen years. However, there is nothing to stop me from performing the first half of an overhead press, so out of curiosity I've begun doing just that to see what, if any, effect it has on my shoulder development.

One of my favourite machine exercises is the seated row - the gym I currently train at has a nice Panatta unit. When I'm unable to complete a full rep on the row, I can continue to squeeze out a few more LPs. Again, I plan to try this for a while and gauge the results.

Anyways, hopefully this article provides some clarity to the topic of lengthened partials.

Let me know what you guys think. Have you tried lengthened partials? Did they set your workouts on fire, or did they leave you colder than an ice bath in the Antarctic?

References

Pallarés JG, et al. Effects of range of motion on resistance training adaptations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 2021; 31: 1866–1881.

https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.14006McMahon G, et al. Impact of Range of Motion During Ecologically Valid Resistance Training Protocols on Muscle Size, Subcutaneous Fat, and Strength. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 2014; 28 (1): 245–255.

https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Fulltext/2014/01000/Impact_of_Range_of_Motion_During_Ecologically.32.aspxStasinaki A, et al. Triceps brachii muscle strength and architectural adaptations with resistance training exercises at short or long fascicle length. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 2018; 3 (2).

https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk3020028Pedrosa GF, et al. Partial range of motion training elicits favorable improvements in muscular adaptations when carried out at long muscle lengths. European Journal of Sport Science, 2021: 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.1927199Pedrosa GF, et al. Training in the Initial Range of Motion Promotes Greater Muscle Adaptations Than at Final in the Arm Curl. Sports, 2023; 11 (2): 39.

https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11020039Sato S, et al. Elbow Joint Angles in Elbow Flexor Unilateral Resistance Exercise Training Determine Its Effects on Muscle Strength and Thickness of Trained and Non-trained Arms. Frontiers in Physiology, Sep 16, 2021; 12: 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.734509Kassiano W, et al. Greater gastrocnemius muscle hypertrophy after partial range of motion training carried out at long muscle lengths. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2023; 37 (9): 1746–1753.

https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/fulltext/2023/09000/greater_gastrocnemius_muscle_hypertrophy_after.3.aspxPedrosa GF, et al. Partial range of motion training elicits favorable improvements in muscular adaptations when carried out at long muscle lengths. European Journal of Sport Science, 2021: 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.1927199Kassiano W, et al. Greater gastrocnemius muscle hypertrophy after partial range of motion training carried out at long muscle lengths. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2023; 37 (9): 1746–1753.

https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/fulltext/2023/09000/greater_gastrocnemius_muscle_hypertrophy_after.3.aspxGoto M, et al. Partial Range of Motion Exercise Is Effective for Facilitating Muscle Hypertrophy and Function Through Sustained Intramuscular Hypoxia in Young Trained Men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2019; 33 (5): 1286–1294.

https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002051Werkhausen A, et al. Adaptations to explosive resistance training with partial range of motion are not inferior to full range of motion. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 2021; 31: 1026–1035.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/sms.13921Wolf M, et al. Lengthened Partial Repetitions Elicit Similar Muscular Adaptations as a Full Range of Motion During Resistance Training in Trained Individuals. SportRχiv, 2024.

https://sportrxiv.org/index.php/server/preprint/view/455Larsen S, et al. Resistance training beyond momentary failure: The effects of lengthened supersets on muscle hypertrophy in the gastrocnemius. SportRxiv, 2024.

https://sportrxiv.org/index.php/server/preprint/view/414Vigotsky A, et al. Methods matter: the relationship between strength and hypertrophy depends on methods of measurement and analysis. PeerJ, 2018; 6: e5071; DOI 10.7717/peerj.5071

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29967737/

Leave a Reply