Is this really how evolution programmed us to eat?

The nutritional habits of our Paleolithic and Neolithic forebears, along with those of modern era hunter-gatherers, constitute a serious field of study that has filled thousands of journal pages and given rise to countless academic texts.

It's a valuable area of research that provides much-needed insight into why staples like meat are well-tolerated by humans, yet foods whose widespread consumption began much later in the course of human evolution (such as cereal grains, dairy) can be problematic for significant numbers of people.

It also explains why certain populations seem to tolerate some foods better than others. For example, Scandinavians and certain African nomad populations began drinking milk thousands of years before anyone else; these same populations have the highest persistence of the lactase enzyme into adulthood. Lactase is the enzyme that allows for efficient digestion of the milk sugar lactose.

Unfortunately, the Paleo Diet craze of the early 2000s took the findings from a serious field of research, and distorted them for commercial and ideological purposes. The "we evolved to eat this way" paradigm was seized upon by everyone from 100% meat proponents to 100% raw vegan authors in order to claim their diet was the one true evolutionarily-correct way to eat.

Any Paleontologist or ethnographic researcher worth his salt will readily tell you that, for all its flaws, humanity has proved a remarkably adaptable entity that has been able to settle in greatly disparate and often marginal environments and subsist on a wide variety of foods and macronutrient intakes. Observations of recent hunter-gatherer societies indicated higher plant and carbohydrate intakes in tropical regions, with increasing proportions of protein and fat at increasingly higher latitudes. A more recent study of hunter-gatherer diets that confined its analysis solely to tropical regions still found a wide range of macronutrient intakes.

The reality is that a 'Paleo Diet' could be anything from low-fat, high-carbohydrate to high-fat, low-carbohydrate. The two paradigms we can rule out, however, are vegetarianism and veganism. Except during brief periods of wild game scarcity, the one unifying component of human diets was the consumption of animal muscle and organs.

The Paleo diet craze was a textbook classic example of taking something with a kernel of truth, and building it into a load of highly dogmatic codswallop.

As an example of the Luddite mentality that pervaded segments of the Paleo 'community,' some proponents advised against nutritional supplements - for no other reason than Stone Age humans didn't consume them, so neither should we.

Science has long since established that, for around 30 minutes after you complete a bout of vigorous exercise, activity of an enzyme called glycogen synthase is greatly elevated. That means that, right after a workout, your ability to replenish glycogen is greatly accelerated. However, to replenish glycogen, you need to ingest carbohydrates. This is why most high-level endurance athletes nowadays consume a bolus of liquid carbohydrates immediately after completing a workout or event.

Did Stone Age humans ingest a bunch of rapidly-absorbed carbs right after a bout of strenuous activity?

I have no idea. I wasn't around then. Neither were any of the 'Paleo' gurus who forbid the consumption of high-GI carbs right after a workout.

But the fact this response exists means that, somewhere along the line, Mama Nature endowed us with a simple opportunity to accelerate our recovery from strenuous activity - all we had to do was take in a bunch of carbs right after training. Numerous studies have shown that adding branch-chain amino acids or whey protein to the mix can enhance the anabolic/anti-catabolic effect, leading to greater lean mass gains.

Am I going to forgo this opportunity because post-workout drinks have been declared "non-Paleo" by some joker who thinks growing a beard, doing CrossFit and eating beef jerky makes him a caveman?

Not bloody likely.

Am I going to forgo the documented benefits of nutritional supplements because there was no GNC or iHerb back in the Stone Age?

Yeah, right.

Stone Age humans were limited to whatever resources they had available to them, at the time and at their location. If something that didn't exist back then has since been proven beneficial - like nutritional supplements, or high-glycemic peri- and post-workout carb drinks - is it an intelligent course of action to eschew it simply because the cavemen didn't eat or do it?

Or is that just being a mindless dogmatist?

Critics had a field day with the inherent contradictions of the Paleo paradigm.

Even if there was one 'true' Paleo diet, how did we validate its long-term effects when average life expectancy in the pre-industrial era was around 30 years of age? Heck, hardcore drug addicts live longer than that nowadays.

Was it really wise, in pursuit of health and longevity, to be blindly following the alleged dietary and exercise habits of people who rarely made it into their forties?

If Stone Age folk were truly living in evolutionary correct bliss, why didn't adherents more closely follow a Stone Age lifestyle? If we hadn't had enough time to adapt to wheat, we had even less to adapt to motorized transport, air conditioning, synthetic clothing and regular bathing - so shouldn't we give them up too?

The inconsistencies and occasional absurdities of the commercialized Paleo paradigm eventually rendered it of questionable relevance to many. The paradigm also lost its appeal among highly active folks, who found the curtailed choice of carbohydrate foods limiting. An abundance of research has shown that liquid carbohydrate consumption improves performance during prolonged exercise. But if liquid carbs are a 'primal' no-go, what are we left with - eating sweet potato while powering up a steep hill, two hours into a bike ride?

Good luck with that.

As with low-carb eating, the Paleo diet gradually lost its prime time status. Again, a mix of hyperbole, unrealistic claims and untenable pseudoscience guaranteed a large portion of adherents would end up disappointed.

So let's fast forward to the present.

The Carnivore Craze

If you took a ketogenic low-carb diet, and mated it with the insistence by some that Stone Age humans only ate meat, what you'd end up with is the “Carnivore Diet.”

Diets like Atkins allowed for the gradual reintroduction of carbs after an initial keto phase. Mirroring the vegan practice of making 'fake' versions of supposedly unhealthy foods, low-carb companies made fortunes selling low-carb bars laden with alcohol sugars and pasta products made with ... for crying out loud ... soy flour.

As someone from an Italian background, you have no idea how much it hurt to write that.

The Carnivore Diet, in contrast, does not allow for Atkins Advantage bars or soy pasta. In its strictest application, this diet contains meat.

That’s it. Just meat.

Slightly more flexible variants of the Carnivore regimen allow for consumption of egg and dairy products.

A lacto-ovo-carnivore diet, if you will.

A Carnivore Diet, therefore, is essentially an elimination diet. In one fell swoop, it eliminates a vast array of potentially problematic food items, such as gluten-containing grains, cereal fibres and their high anti-nutrient contents, refined sugars and high-GI carbs, an endless array of hard-to-pronounce food additives, plant foods with pesticide and herbicide residues, nightshades, lactose ... the list goes on.

Which would go a long way towards explaining why adherents of the Carnivore Diet often report improvements in gastrointestinal issues and health conditions indicative of food allergy or sensitivity.

Meat: It Does a Body Good

As a result of being a universal dietary staple for over two million years, one to which we've had ample time to adapt, allergies and sensitivities to the flesh of terrestrial animals are extremely rare.

Plant foods, in contrast, are a far more erratic proposition.

Hardcore Paleo dogma dictated avoidance of cereal grains, because cavemen didn't eat them to any meaningful degree. Widespread consumption of cereal grains kicked off in earnest around 10,000 years ago with the advent of agriculture in the area now referred to as the Middle East. From there, cereal grain cultivation spread around the world, appearing in some areas much later than others.

The different exposure periods to the world's most widely consumed staple - wheat - may help explain why there is such a disparate response to this and other gluten-containing grains. Modern humans reside on a spectrum that encompasses Tolerance/No Adverse Effect > Gluten Sensitivity > Celiac Disease.

The blanket statement that humans are not adapted to consumption of cereal grains is simplistic and wrong. Many members of the human species have consumed cereal grains on a daily basis, without any evidence of harm, surviving into their 80s and 90s and sometimes beyond. The existence of celiac disease and gluten intolerance, however, shows not all humans have adapted to gluten-containing grains.

The Refreshing Lack of Carnitards. Well, Mostly.

Excepting the occasional bearded fraudster who injects $11,000 of human growth hormone monthly then attributes their muscularity to eating dicks, balls, liver and 'Ancestral' supplements, the Carnivore movement seems a little more grounded than the hopelessly hyperbolic low-carb fad of the 2000s.

Maybe I missed it, but I'm not seeing a proliferation of chubby Carnivore diet clones rushing to get their own books to market pimping nonsensical "metabolic advantages" and irresponsible "eat all you want!" claims - as happened with low-carb during the late 1990s and early 2000s.

I've yet to come across a fat Carnivore proponent that furiously tried to tell lean people like me that we have it all wrong about fat loss - a bemusing and commonplace occurrence during the surreal low-carb years.

While I can foresee longer-term issues for some people following the Carnivore Diet - which I'll discuss in subsequent installments - many of the health benefits being reported thus far are tenable and have a sound scientific underpinning.

That, of course, doesn't mean there are no dubious claims being made for the Carnivore Diet.

Reminiscent of the Paleo gurus, many promoters of this paradigm are claiming that a meat-only diet is the dietary pattern we humans evolved to eat, and they are insisting it is fine and dandy to consume such a diet on a long-term basis.

They issue these claims while standing upon a very thin foundation of research.

Scanning through online Carnivore-type websites, three research themes repeatedly stand out: The Bellevue Experiment, ethnographic observations of Eskimo populations, and carbon isotope studies.

Let's take a look at each of these, and find out if they really show what certain Carnivore Diet promoters claim.

The Bellevue Experiment

In academic circles, the name Vilhjalmur Stefansson is a controversial one, with some historians believing him responsible for the sinking of the Canadian Arctic Expedition (CAE) ship Karluk near Wrangel Island, Siberia, in January 1914.

The anti-carb crowd, however, exalted Stefansson during the Atkins era because of his promotion of a 100% animal food diet. It seems he's become a favorite of certain Carnivore proponents also.

It all began when the infamous explorer spent several years in the early 1900's living with Eskimos and partaking of their fish-based diet. While initially reluctant, Stefansson said he eventually came to enjoy his newly-adopted arctic diet, and wrote both of his own sense of well-being and the good health of his Eskimo hosts.

Stefansson claimed the Eskimos enjoyed a low incidence of diseases commonplace in more modernized societies, and that these diseases became more common among Eskimos who began consuming Western-style processed foods.

After meeting with Stefansson and learning of his experiences, a number of influential medical authorities and researchers warmed to the idea of conducting an experiment that would examine the effects, negative or positive, of a diet comprised entirely of meat. As a result, Stefansson and Karsen Anderson, who had accompanied the former in the arctic for three years, took part in a unique study in which they ate nothing but meat for a period of 12 months.

There was actually a third subject: Dr. Eugene Du Bois, one of the co-authors of the published Bellevue Experiment reports. However, Du Bois spent only ten days on the all-meat diet, and found it difficult to adjust to the regimen.

Stefansson and Anderson spent the first few months of the experiment under close observation at Bellevue Hospital in New York. The subjects continued their all-meat diet at home, and the continued presence of elevated ketones would indicate they adhered to a ketogenic diet. Stefansson ate lamb frequently while Anderson ate beef almost exclusively.

The two explorers were regularly monitored by a team of specialists, paying special attention to any evidence of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or kidney damage, as well as vitamin C or calcium deficiency.

After a year on the all-meat diet, Stefansson lost 2.5kg while averaging 2,100 calories of fat and 550 of protein per day.

Anderson, with a similar protein and fat intake, lost 3 kg.

The researchers reported that in neither subject was there any subjective or objective evidence of a decrease in physical or mental vigor.

Anderson's initial blood pressure reading of 140/80 dropped to 120/80 during the study.

We are told that, towards the end of the experiment, a pneumonia epidemic swept New York, afflicting many of the hospital's patients and staff, including Anderson, who at the time was undergoing observations in the metabolic ward. While fifty percent of these patients allegedly died, Anderson experienced a relatively brief period of illness, responded well to treatment, and made a quick recovery.

Both men remained apparently healthy during the experiment, mocking the dire predictions made by some commentators at the commencement of the study.

And everyone lived happily ever after, according to the low-carb, Paleo and Carnivore camps.

Okay, let's now inject a little reality into the conversation.

Both men led sedentary lives throughout the study. Meaning they did not exercise, they did no manual labor, they did not exert themselves. So while the study tells us an all-meat diet can sustain two men doing little physical activity, it tells us nothing about the effect of this diet on active people.

The claim that Bellevue hospital experienced a pneumonia case fatality rate of 50% raises eyebrows, given that the US case fatality rate during the pneumonia/flu season of 1928-1929 was 0.56%. Why the hospital, including staff members, experienced such an astronomical fatality rate is not explained. Needless to say, Anderson's survival was likely due, not to some immune-fortifying effect of the all-meat diet, but his entering the hospital as a healthy non-patient and enjoying close monitoring by specialist staff while sequestered in a metabolic ward.

In addition to Anderson's brief bout of pneumonia, episodes of pharyngitis were suffered by both subjects. Stefansson experienced remission of his mild gingivitis but increased tartar formation on his teeth.

Those who gushingly cite this study neglect to mention that throughout much of the study, Stefansson and Anderson were in negative nitrogen balance. Which means, despite eating an all-meat diet, they were often in a state favoring breakdown rather than accretion of lean mass.

Anderson displayed a negative calcium balance throughout the entire experiment, while Stefansson showed a negative calcium balance on seven of the 10 occasions he was tested. This indicates the diet of both subjects induced calcium deficiency.

So yes, Stefansson and Anderson were still standing upright after 12 months on an all-meat diet. But the experiment's outcomes were not as glowing as what some folks would have you believe.

Stefansson evidently went on and off his 'carnivore' diet throughout his life. In an article that appeared in Harper’s Bazaar in 1936, he wrote:

“More than twenty-five years have passed since the completion of my first twelve months on meat and more than six years since the completion in New York of my sixth full meat year. All the rest of my life I have been a heavy meat eater, and I am now fifty-six.”

Stefansson suffered a minor stroke in 1952, then a more serious one in 1958 that forced him to drastically cut back his teaching activities. He suffered his final and fatal stroke in 1962, aged 82. While he enjoyed greater longevity than the likes of Atkins and Pritikin, I've got numerous pasta- and bread-eating relatives who, despite difficult lives, lived well past 82, some into their 90s.

If I started pimping omnivorous diets containing bread and pasta for longevity, the reality is that I'd be doing so from a much firmer anecdotal base than anyone citing the Bellevue Experiment.

The reality is that the Bellevue experiment doesn't prove much of anything other than an all-meat diet can sustain two sedentary blokes in New York for a year. They might be calcium deficient and in negative nitrogen balance, and they may even get pneumonia and pharyngitis, but so long as they stay away from intubators, remdesivir and medazolam, they won't die.

The Eskimo Diet: Fact vs Fiction

If I had a dollar for every time someone mentioned the Eskimos in support of low-carb and Paleo eating, I'd have enough money to build a giant, igloo-shaped mansion with a fleet of gold-plated dog sleds parked out front.

The Eskimos, to believe the hype, are a shining testament to the virtues of ketogenic/primal/ancestral/Paleo/Stone Age eating. They don't get heart disease, they don't get diabetes, they're as fit as sled dogs, and their teeth look like something out of a Colgate commercial. And they owe it all to an extremely low-carb diet comprised of fish, seal and whale blubber.

Or so we're told.

Ketogenic diets may have been routine among Eskimos prior to contact with white populations, but their diets during the periods when researchers observed low rates of heart disease were often non-ketogenic, thanks to the introduction of cereals and sugars. Native plant foods were also consumed when available and great effort was often made to preserve them for consumption during the harsh winter months. A 1980 analysis of Greenland Inuit nutrition reported a mean 38% non-ketogenic carbohydrate intake (127 grams carbohydrate daily).

Nonetheless, the adulterated diet of twentieth century Eskimo populations were still high in protein and fat-rich foods of marine origin. Numerous published reports cited low rates of heart disease among these populations, a phenomenon widely attributed by some researchers to their unusually high intake of omega-3 fatty acids from fatty fish.

Less frequently mentioned is the fact Eskimos lived relatively short lives, often fell prone to infection, suffered high rates of bleeding disorders, and suffered an earlier and more intense onset of age-related bone loss than white Americans (see Mann 1962; Bang 1980; Bang 1980a).

Between 1950-1974, Greenland Eskimos reportedly had lower rates of heart disease, diabetes, thyrotoxicosis, bronchial asthma, multiple sclerosis and psoriasis, but higher rates of epilepsy, apoplexia and overall mortality than the general Danish population. Overall cancer incidence was similar between the two populations.

Granted, the Eskimos were a primitive population living in a marginal environment, but there nevertheless remains very little evidence that their diet, ketogenic or non-ketogenic, was doing anything particularly beneficial for their overall health and longevity. Their protection against ischemic heart disease appears to have been primarily due to exceedingly large amounts of omega-3 fats. The trade-off seems to have been an increased predilection for bleeding disorders.

Most of the ‘evidence’ cited in support of allegedly superb Eskimo health comes from explorers or field workers who visited Eskimo settlements. Among the best-known was Stefansson, who interacted with the Inuit for several years during his 1908-1912 voyage. Others, such as Weston A. Price, stayed for much shorter periods. While the recorded experiences of these visitors make for interesting reading, they represent short-term observations only and give us little insight into long-term morbidity and mortality patterns of traditional Eskimo populations.

There is, however, archaeological evidence showing ancient Eskimos were not immune to osteoporosis, nor were they free from arterial disease. Researchers Michael Zimmerman and George Smith examined the mummified bodies of Eskimo women found in Alaska. The oldest one, dating to about 400 AD, was that of a 53-year-old found on St. Lawrence Island in 1972. Zimmerman and Smith performed a complete autopsy. They found a moderate degree of aortic and coronary atherosclerosis, but no evidence of myocardial infarction. Death was determined to have been traumatic; the woman appeared to have been buried alive in a landslide or earthquake, and asphyxiated.

Two other bodies, dating back to around 1520 AD, belonged to a 25- to 30-year-old female and a 42-45-year old. The women had been trapped and crushed by an avalanche of ice while asleep. The young woman's coronary arteries were free of disease. The older female showed atherosclerosis in her aorta and coronary arteries. The mitral valves of her heart showed focal calcification, possibly from bacterial endocarditis arising from a bout of pneumonia. Both women showed severe osteoporosis, their bone spicules being remarkably thinned and decalcified. As Zimmerman notes: “Osteoporosis is a major health problem for modern Eskimos, the most likely cause being the traditional high-protein diet, which results in metabolic acidosis and consequent calcium loss from the bones.”

A couple of key points are worth noting at this juncture:

Citing the Eskimos in support of the Carnivore Diet seems a little incongruent given the former subsisted largely on marine foods, whereas the Carnivore Diet revolves largely around meat from terrestrial animals. A recent survey of over 2,000 Carnivore Diet adherents around the world - which I’ll discuss shortly - found very few ate fish or seafood on a regular basis.

That aside, when the Eskimo research is taken together with the Bellevue Experiment, the inescapable conclusion is not that diets consisting entirely or mostly of animal foods are the key to awesome health and longevity, but that they seem to increase the risk of calcium deficiency and bone loss.

If someone is determined to adopt or maintain a Carnivore Diet, they should seriously consider adding calcium-rich dairy foods (cultured/fermented or lactose-free), or supplementing with calcium and other bone-building nutrients such as magnesium and boron.

Carbon and Nitrogen Isotope Studies

This is where diet sectarians really get their pseudoscientist on.

Carbon and nitrogen isotope measurements of bone collagen were first used as part of the radiocarbon dating process for determining the age of bone. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, radiocarbon dating researchers observed distinct bone collagen isotope ratios from humans that had consumed marine foods or plants like maize in their diets.

Since then, isotope measurement of bone collagen has become a research field in its own right - whose practitioners readily admit it is an inexact science replete with caveats.

That hasn't stopped low-carb, Paleo and now Carnivore Diet promoters from pretending they can tell exactly what Stone Agers ate based on the results of isotope studies of prehistoric bone and tooth samples.

A typical claim goes something like this: "Isotope studies of bones from paleothic humans show a similar profile to those of [insert preferred carnivorous creature like wolves/lions/etc], therefore, paleolithic humans only ate meat!"

What a crock.

As Laurie J. Reitsema, a University of Georgia anthropologist, wrote in 2013:

"Stable isotope ratios do not reproduce exact menus, but rather distinguish between broad food categories: for example, meat versus plants, terrestrial versus aquatic protein sources, or C4 grasses/cereals vs. C3 fruits/vegetables."

Put simply, the bones of animals/humans who eat meat will show different isotope ratios to those who don't. That's where the certainties end. Just because isotope ratios in the collagen extracted from ancient human bones indicate their original owner consumed meat, doesn't mean he/she consumed no plant foods.

A further problem is that different foods can give overlapping isotope signals. Bogard and Outram cite the results an isotope study of Bronze Age remains from central Asia, the results of which were broadly interpreted as representing high fish consumption. Subsequent archaeological investigation failed to evince evidence of fish consumption, and further isotope analyses suggested dairy was in fact the key dietary source of protein.

The message being that isotope studies need to be interpreted in light of what other available evidence says about dietary habits at a prehistoric site. Jumping to wild conclusions that support one's pet eating pattern might be A-OK among diet fanatics, it doesn't cut it in the worlds of Paleontology and archaeology. As Boogard and Outram caution:

"It is only through close integration of stable isotope investigations with primary bioarchaeological observations that a detailed understanding of foodways, including the full chaîne opératoire of management, procurement, preparation, consumption and discard, becomes possible."

Only vegan fanatics deny that meat was an important component of the human diet for millions of years. And only low-carb/Paleo/Carnivore fanatics would claim with certainty that prehistoric humans were plant-avoiding carnivores based on imprecise isotope studies.

Again, all the available evidence indicates that Paleolithic humans did not eat one universal diet. Their staple foods and macronutrient ratios varied according to location and season. Basically, they made do with what was available to them.

So in addition to the caveat to eat calcium-rich dairy and/or supplement with bone-building minerals, be aware that some Carnivore Diet information providers/influencers are peddling a bunch of free-range nonsense.

OK, But Are There Any Actual Clinical Trials of the Carnivore Diet?

While there is now a significant volume of research on low-carbohydrate diets and prehistoric nutrition, there is very little research on the Carnivore Diet per se.

A few days ago, I typed in "carnivore diet" on PubMed, and retrieved 9,174 results.

I then selected the filters "clinical trial" and "human", which whittled the results down to 37.

Even then, all but one of the results were totally irrelevant. Despite selecting for studies involving humans, many of the results were studies performed on dogs.

The only result with even the remotest relevance was a 2014 paper by David et al, which described an experiment in which ten volunteers aged 21–33 were fed 100% animal food and 100% plant food diets. Each diet was consumed for five consecutive days. The purpose of the study was to observe what impact the diets had on the gut microbiome, which was monitored during the six days after each dietary phase.

The animal food diet increased the abundance of bile-tolerant microorganisms and decreased levels of those that metabolize dietary plant polysaccharides. Microbial activity mirrored differences observed between herbivorous and carnivorous mammals, reflecting trade-offs between carbohydrate and protein fermentation. The study demonstrated that changes in diet can rapidly induce changes in gut microbiota, but this tells us nothing about long-term health effects.

So we have a hot diet trend for which some pretty exuberant claims are being made, yet when I entered the name of that diet into one of the world's largest research databases it retrieved only a single clinical trial involving humans, with the 100% animal food diet lasting all of five (5) days.

Carnivore Dieters Surveyed

Given its very sparse research base, it should come as no surprise that anecdote is playing a large role in popularizing the Carnivore Diet.

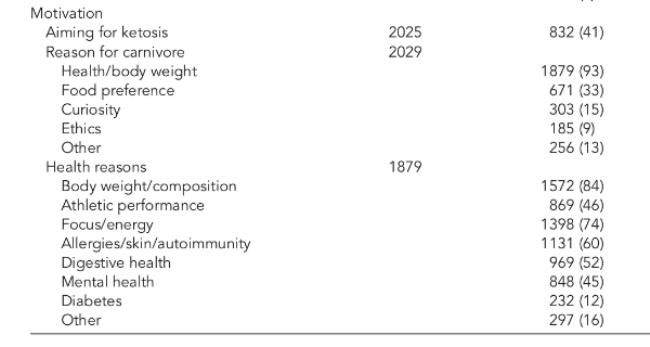

In 2021, Lennerz et al published the results of a survey of 2,029 individuals identifying as following a Carnivore Diet.

The survey respondents were 67% male with a median age of 44 years. The median reported duration of having been on a Carnivore Diet was 14 months, with a range spanning 6 months (the minimum required to participate in the survey) to 28 years.

The bulk of the respondents (1,205) were from the US and Canada, and 83% of the sample were non-Hispanic whites.

"Health/body weight" constituted the primary reason for going Carnivore, with 94% of respondents selecting this option as their motivation.

When quizzed further on health- and weight-related motivations, respondents answered as follows:

Forty-six percent of respondents reported eating red meat each day, while 11% reported eating pork daily. Only 2% reported eating poultry daily, while 3% said they ate seafood daily.

Only 5% reported organ meats daily (the survey was conducted between 30 March and 24 June, 2020 - well before the ramblings of a certain testicle- and liver-munching 'king' went viral).

Eggs and non-milk dairy were consumed by 37% and 36% of respondents, respectively.

Plant food consumption was extremely low among respondents, with starchy vegetables, non-starchy vegetables, legumes, fruit, grains each being consumed by less than 1% of respondents daily.

Eight percent used a multivitamin daily, while 29% reported using "other" vitamin supplement/s daily.

Alcohol was rarely consumed, with 63% reporting frequency of less than once a month or never. More than 50% of participants drank coffee at least daily.

Very few individuals following the diet reported consuming fast foods.

The survey participants reported high levels of overall satisfaction with the diet. The majority perceived no impact on their social life, and neutral or positive support from social contacts.

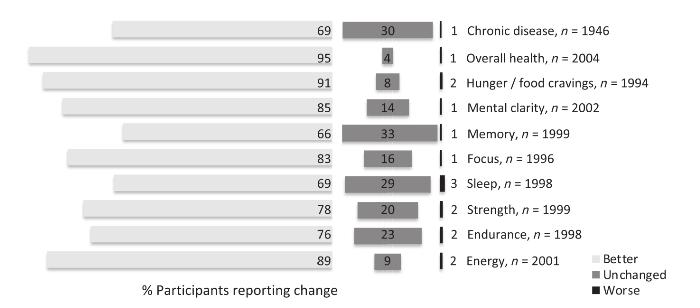

Ninety-five percent of survey respondents reported improved overall health. High rates of improvement were reported for numerous other health conditions, as shown below:

Reported rates of adverse events were low. New or worsened diarrhea occurred in 5.5%, constipation in 3.1%, weight gain in 2.3%, muscle cramps in 4.0%, hair loss or thinning in 1.9%, insomnia in 1.7%, dry skin in 1.4%, itchiness in 1.1%, heart rate changes in 1.1%, brittle fingernails in 1.0%, and menstrual irregularity in 1.0%.

Taking the results at face value, the Carnivore Diet appears to be an extremely safe and effective eating regimen.

However, these results should not be taken at face value, because they come with a number of caveats.

One of the authors was David S Ludwig, who has authored low-carbohydrate diet books and who has previously co-authored research with low-carb diet authors Jeff Volek, Eric Westman, and notorious anti-carb pseudoscientist Gary Taubes.

To be fair to Ludwig, he and his Carnivore paper co-authors were quite forthright about the study's numerous limitations, and they did not use the paper to make any health or body composition claims for the Carnivore Diet.

The survey respondents were recruited from open social media 'communities' dedicated to carnivore and very-low-carb diets: World Carnivore Tribe, Facebook, 23%; Instagram, 18%; r/Zerocarnb, Reddit, 7%; Zeroing in on Health, Facebook, 5%; Twitter, 5%; other, 42%.

As a result, the results were always going to be heavily biased in favor of the Carnivore Diet. Active participants on such websites tend to be enthusiastic and committed to the website's target dietary plan - these websites often act as a magnet for zealots.

It is routine on sectarian dietary websites for people who don't experience success or who suffer adverse effects to be told they are doing something wrong. It's never the fault of the diet, but the unsuccessful dieter. These users will often soldier on under the burden of self-blame, until commonsense finally kicks in and they abandon the diet. The latter will obviously be underrepresented in online surveys like the one conducted by Lennerz et al.

The survey is a snapshot in time and, with a median reported duration of 14 months, tells us little about the long-term prognosis for people following Carnivore diets.

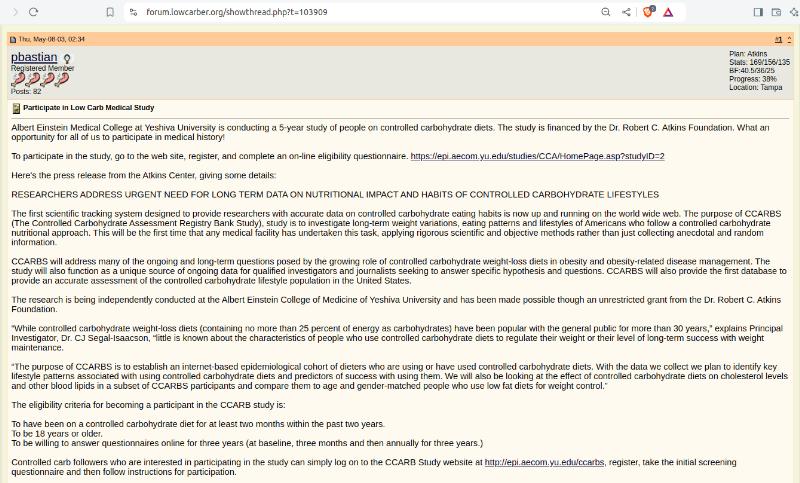

In the early 2000s, a low-carbohydrate diet registry dubbed the CCARBS Study was formed. This was in response to the National Weight Control registry, which appeared skewed towards finding favorable outcomes for low-fat diets. CCARBS aimed to recruit participants who were currently following a low-carb diet and planned to do so for the next three years, in order to gauge adherence and weight loss success. Low-carb websites and forums rallied users and readers to register for the study. This included the internet's biggest low-carb forum, Active LowCarber Forums, a nut farm of zealotry where those who dare say anything critical of low-carb diets are indeed Actively slandered, no matter how much solid science they've got to back them up.

So unlike the static Carnivore survey, CCARBS was a follow-up study.

No published papers materialized from CCARBS, and the study website no longer exists. The only fruit borne from the study are a couple of hard-to-find abstracts (Segal-Issacson. One Year Data From A Prospective Cohort of Low Carbohydrate Dieters. 2004 North American Society for the Study of Obesity Conference; Segal-Isaacson CJ, Ginsberg M. Weight loss and dietary patterns among long-term low carb dieters. Obesity Research, Sep, 2005; 13: A210-A211).

The only of these abstracts I could find online was the conference presentation, reprinted at the Atkins site. It goes a long way towards explaining why CCARBS quietly disappeared.

At one year, more people had gained weight on their low-carb diet than lost weight (34.5% versus 26.5%, respectively) - not at all impressive for a diet that was relentlessly hyped as the ultimate weight loss solution. Most relevant to the present discussion is that, at one year, 75% of CCARBS participants reported they were still on a low or controlled carbohydrate diet.

That's an attrition rate of 25% in only 12 months. How many dieters remained at three years, the time period originally set by the researchers?

And how many of those participants do you think are still following a low-carb diet some twenty years later?

So even in a study funded by the Dr. Robert C. Atkins Foundation, and featuring participants recruited from zealous online echo chambers, a quarter of participants who vowed to follow the diet for three years couldn't do so for 12 months.

So no matter how high the survey respondents in Lennerz et al rated their satisfaction with the diet, the reality is that a significant portion of those respondents are likely to eventually abandon the diet.

For some, the novelty will wear off or they will get bored with the limited food choices.

Others will find the initial health improvements seem to have dissipated, or have been replaced by other health issues.

Yet others will discover that a very low-carb Carnivore Diet is impairing their athletic performance.

Those last two possibilities are what we will delve into over coming installments. Please note these installments will be reserved for my paid subscribers.

Before I close, I'll remind people that I’m not a dictator, and I have no aspirations to become one. I ain't your mama or carer, so you make your own decisions. My goal is to provide factual information, focusing on the science. This is a mission that frequently puts me at odds with those who provide incorrect information and pseudoscience, and their sometimes unhinged followers.

It never ceases to amaze me just how many folks regard their preferred dietary paradigm as some sort of unassailable religious text. These clowns go off like a bunch of angry jihadists at anyone who criticizes or even questions their pet diet, but when you ask them to back up their vitriol with some actual science, they fail to do so every. freaking. time.

I'm not saying the Carnivore Diet is bad. I'm not saying it's good. I don't dispute that people have experienced improvements on the diet - by effectively serving as an elimination diet, I would fully expect at least some participants suffering food sensitivities/allergies and/or gastrointestinal issues to experience improvements.

By removing all or most carbohydrates from the diet - especially refined sugars - I would fully expect at least some participants to experience initial improvements in markers of glycemic control.

I’m not about to tell someone who is experiencing benefits from a certain diet to stop that diet simply because it’s not my preferred nutritional modality.

My issue is with unrealistic and unscientific claims. What I do dispute is any claim or inference that Carnivore dieting is the true evolutionarily correct way of eating, that everyone who follows it will benefit, and that there are no potential long-term health risks from the diet.

All three claims are nonsense.

If you're currently following a Carnivore diet, or you plan to, then it behooves you to be aware of the potential pitfalls. Learning about these potential shortcomings is not being an infidel or a traitor - it's being a rational, grown-ass adult.

Peace, love and ceramic bike grease,

Anthony.

Leave a Reply