Taking a look at the ward research.

In Part 1, we looked at studies involving folks performing weight training and eating hypercaloric diets in order to gain muscular mass.

The content below was originally paywalled.

Those studies reported caloric intakes ranging from 42.6 to 67.5 calories per kg of body weight daily, with a wide range of results.

For example, male trainees in a study by Rozenek et al reportedly consumed 57 calories per kg of body weight and gained 3.1 kg over 8 weeks.

Spillane and Willoughby, meanwhile, reported that subjects with a relatively low intake of 43.5 calories per kg of body weight gained 3.8 kg over 8 weeks.

The male trainees recruited by Smith et al, in contrast, reportedly consumed 52.3 calories per kg of body weight and gained 5.8 kg over 6 weeks.

All the above studies featured similar high protein intakes, yet obtained contrasting results.

The likely reason is that all these studies were free-living studies that relied on self-reported dietary intake data. There is a large volume of research to show dietary self-reports are generally about as reliable as an Australian politician.

So in this article, we'll take a look at the metabolic ward research involving subjects deliberately fed hypercaloric diets. None of them involved resistance training as an intervention; the subjects were either sedentary or mildly active during the overfeeding periods. However, given the relatively low calorie burn from a low-volume resistance training regime, these studies give us an idea of the kind of weight gain we can expect from eating a set amount of calories each day.

To keep things relevant and concise, I've omitted the numerous ward studies with very brief overfeeding periods. As with weight loss, few if any people achieve their weight gain goals in a week. The shortest overfeed duration in the studies discussed below was 19 days, while the longest was 100 days.

In addition to providing guidance to those wanting to gain muscular size, the ward overfeeding studies help to dispel some common myths about weight gain and loss.

This group of UK researchers overfed six young adult males for 42 days while housed in a metabolic unit. The mean body weight of the subjects at baseline was only 64 kg (this was 1980, well before the bloated aftermath of the low-fat, high-tech era).

Mean caloric intake prior to the overfeed was 3,010, compared to 4,500 during. The latter equates to a daily energy intake of 70.3 calories per kg of baseline bodyweight.

The percentages of energy from protein, fat, carbohydrate, and alcohol were 12%, 43%, 38%, and 7%, respectively, during the overeating period.

By day 42, the subjects' mean body weight increased by 6 kg (range 3.75 to 8.5 kg), or +10% of the initial value.

A mean 58% of the weight gain was fat. Body fat increased by an average 3.7 kg (range 1.1 to 5.8 kg), taking the average body fat percentage from 15% to 19%.

The subject who gained 8.5 kg - a pretty sizable gain in only 6 weeks - began the study weighing 62.1 kg. During the overfeed, he averaged 5,620 calories per day, which works out to a mighty 90.5 calories per kilogram!

Now that's a man on a mission.

Welle and Campbell recruited seven men aged 19-36 years with a mean body weight of 69 kg.

During the 20 day overfeed, the subjects were fed around 1,800 calories above their baseline requirement. To achieve this hypercaloric intake, their diet was supplemented with glucose polymer solution (aka maltodextrin) to bring mean total energy intake to 3,987 calories per day (57.8 calories per kilogram of body weight per day). This resulted in a dietary macronutrient ratio of 8% protein, 22% fat, 70% carbohydrate.

Throughout the study, physical activity was kept constant. Two subjects lifted weights each day, an activity they'd initiated before the study. No other subject did anything more strenuous than walking. Unfortunately no individual results were presented, only group means, so we don't know how the body composition outcomes of the weight lifters compared with those of the other subjects.

During the 20-day overfeeding period, the subjects gained an average 3.3 kg.

Lean body mass increased in five of seven subjects, with a mean LBM gain of 1.4 kg. In line with other ward studies, 58% of the gain was fat mass.

Resting metabolic rate, measured in the morning before any meals were consumed, rose by 11.5% during the overfeeding period. The ratio of RMR to LBM increased by 10%, and serum T3 levels were increased by 32% at the end of overfeeding.

In 1986, Forbes, Welle et al published the results of another overfeeding ward study. Most ward studies have featured male subjects, but in this study all but two of the subjects were female. Two males and 13 females were housed in the Clinical Research Center for 24-28 days. They ranged in age from 18 to 41 years, in weight from 44 to 93 kg, with body fat % ranging from around 8.6% to 36%. All had been relatively weight stable during the past 2 years.

During the first week they were given a eucaloric diet designed to maintain body weight. They were then given an additional 717 calories daily for 2 days, followed by an extra 1,195-1,793 cals/day for the next 15-19 days, making a total of 17-21 days of overfeeding.

The authors don't give average figures, but we'll assume an average overfeeding period of 19 days which, using figures supplied in the paper, gives us an average intake of 4,311 calories per day. Average bodyweight of the 15 subjects was 64.7 kg, which equates to an energy intake of 67 calories/kg/day.

The subjects were encouraged to take walks in the hospital grounds or to exercise on a treadmill (4 km/h, zero grade) for 20 minutes twice daily. Some attended classes at the university (0.7 km from the hospital); others worked at clerical jobs part-time. Their activity patterns fell into the WHO category of ‘light physical activity’. Every effort was made to keep each individual’s activity pattern the same throughout the entire stay at the ward.

All the subjects gained weight, with an average of 4.4 kg (range 3.5 to 5.8 kg). Fourteen of the 15 had an increase in lean body mass. On average, 51 % of their gain consisted of LBM; individually, lean mass gains ranged from 0% to 108% of the body weight gain.

Weight gain occurred at a fairly uniform rate during the period of overfeeding. Although several female subjects claimed they usually gained weight before menstruation, the occurrence of menses during the study had little effect on their weight gain trajectory. None took oral contraceptive drugs during the study or for the week before admission to the Clinical Research Center.

The average increase in RMR was 8.7%, marginally greater than the increase in body weight of 6.0%.

Four of the female subjects were smokers who smoked more than 20 cigarettes daily throughout the study period; they had about the same response to overfeeding as the nine female non-smokers.

One of the subjects (weight 49 kg) stated she had “tried without success” to gain weight for several years, yet actually gained as readily as the others (+3.92 kg) during the study. Another female subject made the comment: "I had always thought that I gained weight very easily, but I actually had to work very hard to put on those extra 10 pounds (4.46 kg) in 3 weeks."

This study included seven lean and 3 overweight men. It included a six-week overfeed where the men were fed a diet supplying 150% of their baseline energy requirements.

At baseline, the 'lean' subjects averaged 68.9 kg and 17.7% body fat, which isn't really lean. The overweight subjects averaged 84 kg and 29.7% body fat.

In line with what personal trainers hear on a regular basis, the lean(er) subjects claimed to have difficulty gaining weight, while the overweight subjects claimed to eat less than their appetite, to gain weight easily, and to have difficulty losing weight.

Not wanting to sound like a jaded trainer who has heard it all before, but ... sure.

Mean daily calorie consumption at baseline was 3,177 calories, compared to 4,681 calories during the overfeed. Given a mean baseline weight of 73.4 kg, that equates to 63.8 calories/kg/day.

After 42 days, the mean weight gain was 7.6 kg. Fat and lean mass gains averaged 4.6 kg and 3.0 kg, respectively.

In contrast to what the participants claimed at the start, there was no rhyme or reason to the subsequent results. The leanest participant at baseline weighed 57.9 kg and sported 11.2% body fat at baseline. He consumed 5,111 calories per day during the overfeed, or 88.3 calories per kg per day. He gained 8.8 kg, the second highest weight gain in the study.

The highest weight gain was experienced by another 'lean' subject, who began the study weighing 75.4 kg with 17.4% body fat. He gained 10.5 kg while averaging 5,636 calories daily, or 74.7 calories/kg/day.

The heaviest overweight subject weighed 89.8 kg with 30% body fat at baseline. He averaged 4,538 calories during the overfeed, or 50.5 calories/kg/day. He gained 7.5 kg.

Another overweight subject started out at 77.6 kg and 29.2% body fat. He averaged 4,371 calories per day, or 56.3 calories/g/day and gained 7.1 kg. The results were similar for the third overweight subject.

Skinny folks often swear black and blue they can't gain weight no matter how much they eat. And we've all heard overweight folks claim they only have to look at food and they gain weight. The individual results cited above suggest that after overweight folks look at food, they go ahead and eat it, and that's why they gain weight.

Similarly, the results show that lean folks who claim "I can't gain weight no matter how much I eat!" are seriously exaggerating the amount of food they consume. Or in the case of active folks, greatly underestimating their daily calorie burn.

Under ward conditions where everyone is actually made to eat a hypercaloric diet, lean subjects gain weight, while overweight subjects who don't overeat to the same degree don't gain weight to the same degree.

The Quebec Twins Study examined twelve pairs of identical twins, comprised of 24 healthy, sedentary men averaging 60.3 kg and 21 years of age.

For the duration of the study, the subjects lived on the campus of Laval University. The subjects were under 24-hour supervision by research assistants who lived with them. Each subject stayed in the unit for 120 days. This included a 14-day baseline weight maintenance period, 3 days before and 3 days after for testing, and 100 days of overfeeding.

During the overfeeding period, the subjects were fed 1,000 calories over their established weight maintenance, 6 days a week. On the remaining day of each week they were fed their baseline daily energy needs. Subjects were thus overfed during 84 of the 100 days. The macronutrient ratio during this period was 15% protein, 35% fat, and 50% carbohydrate.

So in this study, the 'cheat day' actually involved taking a break from the high-calorie diet and eating less.

The researchers measured the mean baseline energy requirement as 2,756 calories. This becomes 3,756 calories per day when the 1,000 calorie surplus is added, or 62.3 calories per kilogram per day.

The subjects’ schedule was largely sedentary and included playing video games, reading, playing cards, watching television, and walking 30 minutes per day.

The overfeeding protocol induced a mean body weight gain of 8.1 kg. Gains in body fat and fat-free mass comprised 67% and 33% of the body weight gain, respectively. These morphological changes accounted for 63% of the total excess energy intake.

Where did the rest of the calories go? After overfeeeding, the researchers observed significant increases in RMR (9.7%), postprandial thermogenesis (the increased energy expenditure caused by digestion and metabolism of a meal), energy cost of walking, and energy cost of weight maintenance.

Those last two reflect the fact that when you put on weight, moving around requires more calories than before because your muscles have to propel a heavier object through space. The extra lean mass will also contribute to an increased calorie demand.

In this study, fecal energy losses did not account for any of the calorie 'shedding' as they were identical before and at the end of the overfeeding protocol.

Where the subjects' mean maintenance energy needs were 2,756 calories at baseline, they were 3,001 calories after the overfeeding phase.

Another noteworthy observation comes from the four-month 'recovery' period after the study. After the overfeeeding phase, the subjects returned to free-living conditions and were encouraged to adopt physical activity and nutrition habits favoring weight loss. During this four months, a mean weight loss of 6.7 kg occurred. The mean decreases in body weight, fat mass, fat-free mass, and body energy noted over the latter period were 82%, 74%, 100%, and 75%, respectively, of the gains induced by overfeeding.

So, in the absence of weight training, a caloric excess of 1,000 calories per day resulted in mostly fat gain. When the overfeeding period ended, the subjects lost all the lean mass they had gained, but still retained some of the extra bodyweight and body fat. This shows how sedentary people, who go through alternating periods of weight gain and weight loss, often end up fatter than before. Even if they return to their previous body weight, their body composition has been unfavorably altered. They are now carrying more fat and less lean mass than previously, even though they weigh the same as before.

This is why it's important to lift weight when losing weight. I've heard people say countless times over the years, "oh, I'll lose the weight first then start weight training," a strategy that makes about as much sense as leaving home with your front door wide open, then returning the next day to close and lock it. By that time, your valuables will probably have been long gone. Resistance training is not just for bodybuilders and linebackers, it offers benefits to just about everybody. You don't need to lift every day for hours on end - studies have shown three brief workouts a week, performing one work set of each exercise to failure, will build muscle and strength.

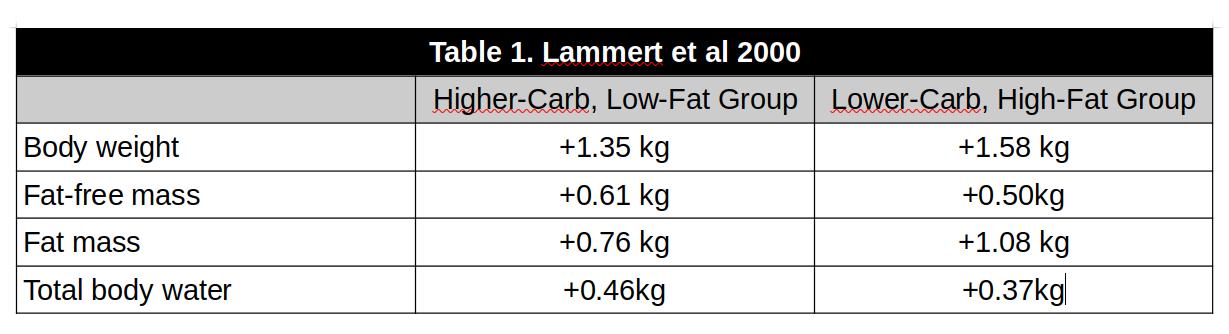

All the studies I've discussed so far have featured a single group of subjects, all fed a similar diet. This study was a randomized, controlled trial from Denmark that compared two hypercaloric diets, containing 78% and 31% of calories from carbohydrate, respectively. Both diets contained 11% protein, the remainder of calories coming from fat.

The researchers enrolled twenty healthy young men, average age 22 years, and divided them into pairs. After an initial baseline period to determine their maintenance requirements, they were housed in the metabolic ward and overfed 1,194 calories above maintenance for 21 days.

Each person in a pair was randomly assigned to the high- carbohydrate or high-fat diet, acting as ‘Siamese’ twins in order to keep the physical activity similar in each pair during the study. Average baseline weight in the higher-carb group was 76.4 kg, compared to 73.4 kg in the high-fat group.

Unlike most ward studies, the subjects did the shopping themselves and prepared their own meals, weighing and recording all food items in accordance with the recipes and instructions given. The research staff regularly, but unannounced, confirmed that the meal preparations and the recording of intake of food, drinks, snacks and sweets took place in accordance with the instructions.

During the overfeeding phase, the high-carb, low-fat group averaged 4,610 calories per day (60 calories per kg of bodyweight).

The lower-carb, high-fat group averaged 4,585 calories daily (62.5 cals/kg bodyweight).

The high-carb group averaged 896 grams of carbohydrate daily, compared to 346 grams daily in the high-fat group.

The high-carb group averaged only 56 grams of fat daily, compared to 289 grams daily in the high-fat group.

The table below shows the mean gains in body weight, body fat, lean mass, and body water of the two groups after the overfeeding phase.

In the higher-carb group, fat and lean mass gains comprised 55% and 45% of the weight gain, respectively. In the high-fat group, the corresponding figures were 68% and 32%, respectively.

There were no differences in fasting and non-fasting blood glucose nor fasting and non-fasting insulin between the two groups.

You might have heard low-carb pseudoscientists claim carbs cause de novo lipogenesis (formation of endogenous fat), so therefore carbs are fattening. Mean hepatic and whole-body de novo lipogenesis were indeed higher in the high-carbohydrate group, but as Table 1 clearly shows, this had no effect on the body weight and composition outcomes. The Danish researchers cited previous research showing DNL from carbohydrate causes an obligatory energy loss as heat of about 19% as compared to about 3% by the direct storage of dietary fat. What is ignored by low-carb and keto zealots - who have long abided by a series of simplistic, religious-like tenets as opposed to scientific reality - is that dietary fat does not need to go through sophisticated, energy-intensive biochemical processes to be converted into body fat because ... it already is fat.

This UK study involved six lean men, who were housed in a metabolic ward for 17 weeks of intermittent overfeeding. This study is helpful because it subjected all six participants to three different levels of excess calorie intake in stepwise fashion: 20%, 40% and 60% calorie surpluses, respectively.

The study kicked off with a 3-week baseline period, where the dietary intake was adjusted to maintain body weight. Having established each participant's maintenance calorie requirement, they were then subjected to the three overfeeding periods, each interspersed with one week of ad libitum food intake.

The mean baseline calorie intake was 2,627 calories.

During the first of the three week overfeeding phases, the researchers aimed for the men to consume a 20% calorie surplus. Mean daily energy intake during this phase was 3,224 calories (a 23% surplus). This equated to 46.9 calories per kg of baseline weight per day.

This was followed by a week of ad libitum eating, then another overeating phase, this time aiming at a 40% calorie surplus. Mean daily intake during this second overfeeding block was 3,726 calories. This equated to 54.2 calories per kg of baseline weight per day.

After another week of ad libitum eating, the men embarked on their final overfeeding phase, this time shooting for a 60% calorie surplus. Mean energy intake during this last overeating phase was 4,251 calories per day. This equated to 61.9 calories per kg of baseline weight per day.

The study finished off with a final 3-week ad libitum phase.

During the 20% overfeeding phase, the mean weight gain was 0.7 kg. Weight remained stable during the subsequent ad libitum phase.

During the 40% overfeeding phase, the mean weight gain was 2.21 kg. There was a small weight loss of 0.44 kg during the subsequent ad libitum week.

During the 60% overfeeding phase, the mean weight gain was 3.21 kg. By this point, the subjects were a mean 5.71 kg heavier than at baseline.

So to no-one's surprise, this study showed a higher calorie surplus led to greater weight gain.

During the following 3-week ad libitum phase, there was a mean weight loss of 2.71 kg, leaving the subjects 3 kg heavier than baseline.

Using doubly labelled water, the researchers determined the mean total daily energy expenditure of the subjects to be 2,651 calories; after the weight gain of the 60% overfeed it was 3,081 calories. A smaller margin was obtained via indirect calorimetry: 2,723 versus 3,033 calories, respectively.

Twenty-five healthy men and women aged 18–35 with BMIs between 19.7–29.6 completed this study. The participants were randomly assigned to one of 3 different protein diets, consumed while living under strict ward conditions.

The mean energy required for weight stabilization during baseline was 2,412 calories per day. Participants were overfed by approximately 40% above the baseline weight maintenance energy requirement (a mean 950 calories per day) for 56 days. The overfeeding diets contained:

5% protein, where all excess energy was fat;

15% of energy from protein;

25% of energy from protein.

At baseline, the low-protein subjects weighed 69.1 kg, the normal-protein subjects weighed 77.6 kg and the high-protein subjects weighed 76.0 kg.

During the overfeeding period, the low-, normal- and high-protein subjects consumed 3,130, 3,508 and 3,439 calories daily. This equates to 45.3, 45.2 and 45.25 calories per kilogram per day.

During the overfeeding period, the mean daily protein intakes were 47 g, 140 g and 228 g in the low-, normal- and high-protein groups, respectively. Expressed as per kilogram of weight, this equates to 0.6 g/kg, 1.8 g/kg and 3.01 g/kg per day, respectively.

Carbohydrate provided 42–43% of calories in all 3 overfeeding diets with the remainder of calories coming from fat: 49%, 42% and 30% in the 5%, 15% and 25% protein diets, respectively.

Subjects were weighed daily and allowed to leave the metabolic unit only under supervision and with permission of the study director. Meal times were supervised by the dietary staff to ensure all foods were eaten.

After eight weeks of overfeeding, all subjects had gained similar amounts of body fat: 3.66 kg, 3.45 kg and 3.44 kg in the 5%, 15% and 25% protein groups, respectively.

The 5% protein group lost 0.70 kg of lean mass, compared to gains of 2.87 kg and 3.18 kg in the 15% and 25% protein groups, respectively.

As a result of the differential lean mass changes, total body weight gain in the 5% protein group was only 3.16 kg, compared to 6.05 kg and 6.51 kg in the 15% and 25% groups, respectively.

So fat gains comprised 57% and 53% in the 15% and 25% protein groups, respectively.

This was despite the increase in 24-hour energy expenditure, measured sporadically throughout the study, being smallest in the low-carb group. The researchers speculated "the low protein group probably reduced nutrient absorption (metabolizable energy) relative to the other groups" i.e. greater fecal and urinary loss of calories, although this wasn't actually measured during the study.

A six-week ward study by by Hollstein et al in which subjects were fed a 2% protein diet at 150% of maintenance calories similarly produced a 3.8 kg weight gain and an even greater 4.5 kg fat gain.

These studies show that very low protein intakes can actually cause lean mass loss even in the face of hypercaloric intakes and concomitant weight gain. If you are looking to gain muscle, excess calories alone are not sufficient - you must be eating adequate protein. Apart from fruitarians and radical vegans, I'm not sure why anyone would want to consume a mere 2%-5% protein, but the bottom line here is if you don't want to look like Harley Johnstone, don't eat like him.

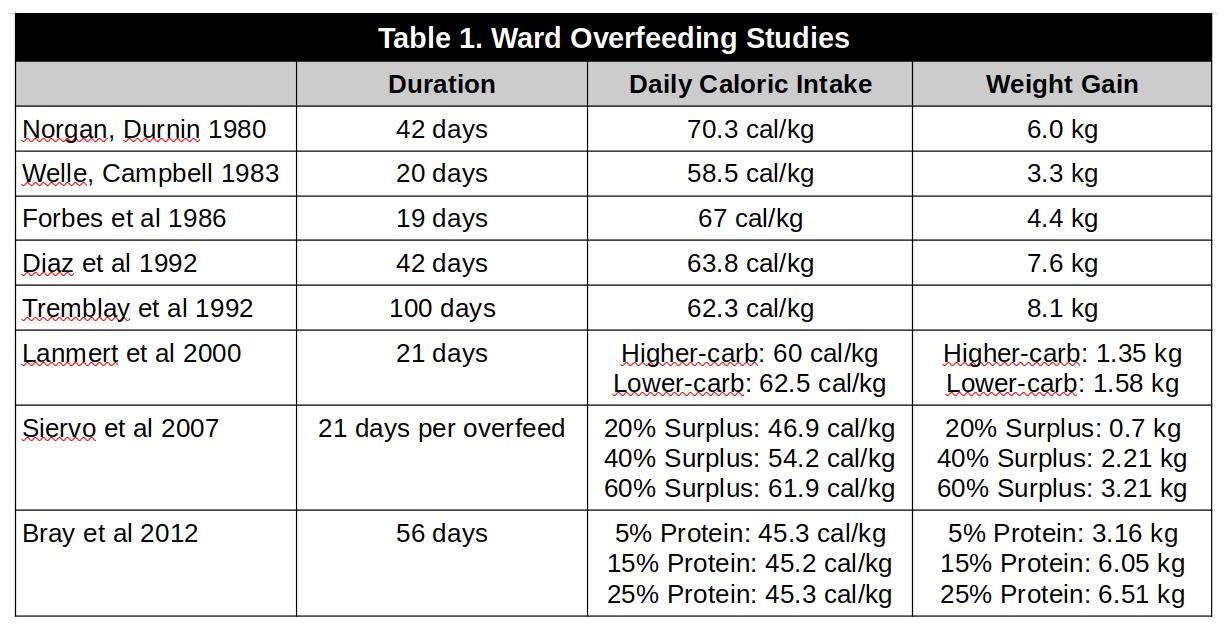

Putting It All Together

As always, compiling the results of multiple studies into a concise visual format helps make sense of it all. Table 1 summarizes the results of the studies above.

Compared to the free-living studies with resistance trainees in Part 1, the ward studies generally featured higher mean caloric intakes, with 6 of the 8 studies incorporating mean caloric intakes between 60 and 70.3 calories/kg/day.

The lowest caloric intakes were seen in Bray 2012, at ~45 cal/kg/day. Despite this, the subjects on the 15% and 25% protein diets gained 6-6.5 kg and 2.87 kg and 3.18 kg of lean mass, respectively, over 8 weeks.

The results show, unsurprisingly, that the longer the overfeed, the greater the weight gain.

While there is variation among the studies, the Siervo study shows that when you take the same group of subjects and subject them to different calorie surpluses under the same ward conditions, their weight gain increases in tandem with the increase in excess calories.

On average, when you overeat and remain sedentary, you can expect around 60% of your weight gain to be comprised of fat.

The ward studies also show that individual weight and fat gain at similar caloric intakes can vary widely, and that the variation bears little relationship with baseline weight or body fat levels.

Therefore, it's impossible to make hard and fast recommendations like "eat X amount of calories and you will gain X amount of weight in X amount of days."

The best we can do is work out some rules of thumb that serve as a starting point, then closely monitor the results and modify the plan as needed.

So ... adding in the calorie burn from a basic weight training routine, I'd be aiming for a minimum of 50 calories per kilogram per day when looking to gain weight. For a 75 kg person, that equates to 3,750 calories per day.

If you engage in other physical pursuits (cycling, running, fight training etc) and are looking to gain weight, I'd be upping the minimum target to 55-60 cal/kg/day. The Garthe et al study, discussed in Part 1, involved elite young athletes looking to gain weight. Reported intakes on those receiving weekly counselling versus those given initial advice then left to their own devices were 50.7 and 39.4 calories/kg/day, respectively. The subsequent weight gains over an average of 10 weeks were 2.7 kg and 1.2 kg, respectively. The athletes in the counselled group reported training almost 18 hours a week, while the ad libitum athletes reported 16 hours a week. I have serious doubts as to whether the reported caloric intakes, especially in the ad libitum group, would have produced any weight gain in athletes with that kind of training volume.

In a 75 kg athlete, for example, 39.4 calories/kg works out to a daily intake of 2,955 calories. In an athlete training 3 hours a day, 6 days a week, that's the kind of intake you'd prescribe for weight loss.

Protein intake, at a bare minimum, should be 1.8 g/kg/day, but I'd prescribe between 2.2-3 g/kg/day. That's the kind of protein intake that would have regular dietitians and the plant-based crowd choking on their soy sausages, always a sign you're on the right track.

The remainder of calories, of course, will need to come from carbohydrate and fat. Hopefully those of you reading this are light drinkers, meaning alcohol will form a negligible part of your caloric intake.

Carbohydrate intake should be adjusted based on your activity levels and glycemic status. I would like to think my readers are well and truly past the low-fat charade, because consuming a hypercaloric low-fat diet can be a great way to get your blood sugar levels bouncing around like a rodeo bull.

Too high a fat intake, in contrast, will leave you prematurely full, making it difficult to consume the required calories. Too much dietary fat is also a great way to spend the day feeling queasy and nauseous.

Eating 3,500 to 6,000 calories per day might sound like great fun, but it can be hard work. If you're one of these 'clean eating' types who thinks good nutrition is surgically trimmed meats, tuna, egg whites and wholegrain-everything (or what I call the Sawdust Diet) and you want to gain weight, then you've got some mental deprogramming to do.

For many folks, trying to fit several thousand calories per day into the traditional three square meal format is going to be pushing the proverbial mierda up a very steep hill, so formatting 4-6 meals a day will be necessary.

One painless way to up your caloric intake is by taking a large liquid serving of calories, comprised of quality protein and a large bolus of carbohydrate, immediately after training.

Don't forget peri-workout consumption during endurance activities like cycling, where consumption of ~60 grams of carbs per hour will not only help keep your calories up but prevent glycogen depletion and boost your performance.

Endurance activities are unsurpassed for cardiovascular conditioning, while activities like boxing, MMA etc are essential if you want to achieve proficiency in those fields.

With weight training, however, aim to do the bare minimum that will achieve muscle and strength gains. Training twice a day, 6 days a week might work great for enhanced, state-sponsored Eastern bloc weightlifters, but there is little in the way of quality evidence to show 3 sets of an exercise are better than 1 for regular trainees (see my article on the topic here). Doing more weight training than necessary simply creates an extra calorie expenditure for which you will have to compensate with even more calories.

The topic of bulking is prone to a substantial serving of hype and BS, so hopefully this helps those of you are wondering where to start or who have had difficulty gaining muscle mass in the past.

As a paid subscriber, you are more than welcome to leave any comments or questions below.

Leave a Reply