This article originally published March 26, 2010.

The Fairy Godfather of Low-Carb Strikes Back – and Strikes Out!

Note: This article contains strong language. Please close this page immediately if you are a minor or easily offended.

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Part 2 of The Great Eades Smackdown, 2010!, where we continue our unmerciful obliteration of the fraudulent claims made by Protein Power author and incurable low-carb shill, Dr. Michael Eades. In his recent nonsensical “dismemberment” of Chapter 1 of my book The Fat Loss Bible, Eades tried to pull off some pretty outrageous whoppers in support of metabolic advantage dogma (MAD). In Part 1 of the Smackdown, I blasted away these lies in systematic fashion, revealing that:

--Eades lied about a pivotal study conducted by University of Rockefeller researchers, claiming it showed a 630 calorie-per day metabolic advantage when it actually showed no such thing;

--Eades first claimed the metabolic advantage was so powerful that it explained the obesity epidemic, but then back pedalled faster than a clown on a unicycle, claiming the effect was so small it can’t even be measured on a bathroom scale;

--Eades’ insistent claim that metabolic ward studies are rife with cheating actually supports a metabolic advantage for high-carb diets, not low-carb diets!

--There is indeed a tiny diet-induced thermogenic metabolic advantage for high-carb diets, but it’s too small to make any noticeable difference in weight loss.

Eades Re-Opens the Floodgates of BS

In Part 1, I predicted that Eades would respond to my Smackdown with yet another load of convoluted pseudoscientific bullpucky that did everything except present actual human evidence for MAD. And that’s exactly what happened here and here.

But on March 10, after over two years of talking smack, throwing insults, and cowardly dodging my requests to pony up with some actual human metabolic ward evidence for MAD, Eades finally fronts up with what he believes to be his killer punch.

And it’s about to get him knocked on his ass…again.

Eades is so desperate he cites experiments by two groups of researchers that I have already thoroughly debunked in my book The Fat Loss Bible. Of course, Eades knows that most of his readers have not and will not read my book, because they are too cowardly to confront any evidence that disputes their closely held MAD beliefs.

The two examples he cites are without question among the sloppiest and poorest possible excuses for ward research ever conducted. In other words, just the kind of evidence that Eades loves. You’re in for a special treat folks, because today I will thoroughly tear these studies apart in far more detail than what I ever did in The Fat Loss Bible, and reveal why anyone who cites them in support of MAD is either totally clueless or a shameless con-artist. Today, we will establish beyond a doubt that Dr. Michael Eades is an intellectually dishonest commentator who simply cannot be trusted to give a complete, impartial, and honest assessment of any evidence pertaining to MAD.

The Prat Lost Its Tongue

The sound of the opening bell is only minutes away…but before we start tearing into the duplicitous Dr.Michael Eades, let’s take a quick look at how he addressed the numerous lies and contradictions that I highlighted from the first instalment of his “dismemberment”.

Eades’ response to the incontrovertible evidence that he lied about the Liebel study?

Silence.

Eades’ response to the fact that his “metabolic ward studies are rife with cheating” argument actually argues for a metabolic advantage of high-carbohydrate diets?

Silence.

Eades’ response to my highlighting of his continued softening MAD stance?

Silence.

Eades’ discussion of the abundance of tightly controlled studies showing absolutely no greater increase in metabolism or diet-induced thermogenesis from low-carb diets or meals?

Silence.

Eades’ response to the fact that high-carb meals tend to induce slightly greater diet-induced thermogenesis than low-carb meals?

Silence.

Why did Eades claim that I believe low-carb diets to be superior for muscle preservation, when I have said no such thing? (in fact, The Fat Loss Bible explains why ketogenic low-carb diets are likely to increase muscle loss).

Again, total silence.

These anomalies all show Eades to be self-contradictory and his arguments to be a load of disingenuous bullpucky. Eades has no rational answer to these fatal flaws in his argument, so he simply ignores them. When his few non-brainwashed readers repeatedly point out that he lied about subject 3 in the Liebel study, he snidely fobs them off by telling them they can’t read and to go re-examine the study. Well, one astute reader did just that and pointed out to me that Eades not only ignored the actual caloric intake of subject 3, but also lied about the corrected caloric intake, which was actually higher on the high-carbohydrate diet. I can’t believe I missed this, but between the fun I was having giving Eades a good hiding (that’s Australian for whoop-ass, mate!) and processing the squillion or so gigabytes of information floating around in my head at any one time, I did – so many thanks to Steinbach over at the Sweat forum for pointing this out.

The truth is that Eades is the one who can’t objectively read a study to save his life.

Sleazy Is As Sleazy Does

The duplicity of Dr. Michael Eades never ceases to amaze me. Just when I think the guy can’t get any more dubious and desperate, he sinks to a stunning new low. Here is a guy who attacks my use of metabolic ward studies, claiming these studies are “rife” with cheating (which actually argues for a metabolic advantage of high-carb diets, given that they are the diets clinically shown to most likely induce higher calorie consumption). But when we read the actual studies, or contact the actual researchers, it becomes readily apparent that many of these studies were meticulously controlled. Eades, however, wants us to ignore these researchers and instead believe him - a biased, lying, shameless low-carb shill with an established history of selective citation and distortion of evidence in order to support his own vested financial agenda.

Fat chance, Doc. I don’t trust people like you who shamelessly ignore the studies that contradict their untenable beliefs and then deliberately misrepresent the small number of remaining studies. You then have the gall to turn around and accuse people like me – who have no vested financial interest in high- or low-carb nutrition, and who have reviewed the evidence in its entirety and laid out our findings for all to see – of being selective, dishonest and biased.

What a joke.

Round 1: Eades Gets Downright Insensible

Eades repeatedly dismisses metabolic ward studies as inadmissible evidence against MAD because he believes they are “rife” with cheating.

So what does he cite in support of MAD in his March 10 article?

A metabolic ward study that was rife with cheating.

Yep, Eades does what all shameless MAD shills have done throughout MAD’s illustrious history – he dredges up the notorious Kekwick and Pawan study that was reported in the Lancet in 1956[Kekwick]. Eades wanks on and on about this study, and by the time he’s finished, he and his followers have once again thoroughly convinced themselves that he’s finally trumped me.

These clowns should go into comedy.

The only thing Eades achieves by citing Kekwick and Pawan is to once again highlight what a self-contradictory dimwit he truly is.

Kekwick and Pawan are incessantly cited by low-carb MAD shills because one of their experiments reported greater weight loss on high-protein and high-fat diets than on high-carb diets, even though all three diets allegedly contained 1,000 calories per day.

According to Kekwik and Pawan, all of the subjects in the high-protein and high-fat diet groups lost weight, with the high-fat group experiencing the greatest weight loss of all. However, despite the very low calorie intake, many of the patients reportedly gained weight during the high-carbohydrate diet.

We are, in all seriousness, supposed to believe that while the patients lost fat on high-fat and high-protein diets, some of these same patients actually gained fat on an isocaloric high-carbohydrate diet, even though no other metabolic ward study has ever replicated this result. We are supposed to believe this, even though body fat was never even measured by the researchers.

So what explains the Kekwick and Pawan findings?

Let’s start with cheating.

Eades makes this study out to be a wonderful example of fastidious metabolic ward research, but the truth is that it was a poorly controlled free-for-all that was rampant with non-compliance. And rest assured, unlike Eades I’m not pulling unfounded allegations from my ass in order to conveniently dismiss a study that fails to support my beliefs.

Kekwick and Pawan themselves were so flabbergasted by the poor compliance of their subjects they were driven to denigrate them in their Lancet paper, writing:

"The first and main hazard was that many of the patients had inadequate personalities. At worst they would cheat and lie, obtaining food from visitors, from trolleys touring the wards, and from neighbouring patients. (Some required almost complete isolation.)"

In Part 1 of The Great Eades Smackdown, 2010! I present the incontrovertible evidence showing that high-protein and high-fat/low-carb diets exert superior satiating effects than low-fat/high-carbohydrate diets. Given that protein and fat have been shown numerous times to exert satiating effects, while low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets (especially the liquid, low-fiber variety used in the Kekwick and Pawan study) often result in ravenous hunger, it's not hard to guess during which diet the participants would have cheated the most.

Because of the atrocious compliance, the researchers were forced to toss away much of their data. The researchers wrote: "The results we report are selected, a considerable number of known failures in discipline being discarded". Note how the researchers included the words "known failures"; how many failures did they not know about? How many of the patients were crafty enough to sneak extra food without being caught? Kekwick and Pawan, by analyzing the remaining data and presenting it as ‘evidence’ in their paper, made a very naïve and dangerous assumption – that because the remaining patients were not caught cheating, they did not cheat. It’s understandable that these researchers, having invested so much time, effort and research funding in their experiments, were reluctant to write off their entire project by admitting their remaining data was of highly suspect quality. Instead, they simply made a huge leap of faith and assumed that their remaining subjects were exceedingly honest individuals, rather than individuals who were simply cunning and/or lucky enough not to get caught cheating.

If you are like me, such naïve assumptions simply will not suffice when assessing the validity of scientific research. Why should we trust Kekwick and Pawan's unlikely results, given their study's inherent flaws? The answer is simple: Unless you are a duplicitous low-carb diet author who is desperately trying to prop up his beloved but dying MAD paradigm, we shouldn't.

Eades however, is more than happy to shove his head even further up his posterior and ignore the numerous flaws inherent in the Kekwick and Pawan experiments. Even when he has previously and incessantly stated that such flaws render metabolic ward studies invalid!

According to Eades, metabolic ward studies are “rife” with cheating, so we should ignore them.

According to Eades, the participants of metabolic ward studies are the dregs of society, a bunch of lower socio-economic dropkicks who can’t be trusted to do anything right. Again, Eades insists that this is further proof that metabolic ward studies should be ignored.

Well, here’s a metabolic ward study that, by the authors’ own admission, was marred by rampant cheating and, by the authors’ own assessment, dominated by subjects with “inadequate personalities”.

But instead of ignoring it, Eades readily cites it as proof of MAD!

Why does he cite a study that fails to meet his very own criteria of acceptable research?

Simple: it’s one of the very few human studies that can be made to look as if it supports what he wants to believe.

Eades’ modus operandi is so transparent that it’s laughable. Like most myopic dogmatists, he adheres to the following strict criteria when assessing evidence relating to MAD:

High quality evidence = that which supports his beloved theory, no matter how shabbily performed and poorly controlled.

Poor quality evidence = that which contradicts his beloved theory, no matter how professionally conducted and tightly controlled.

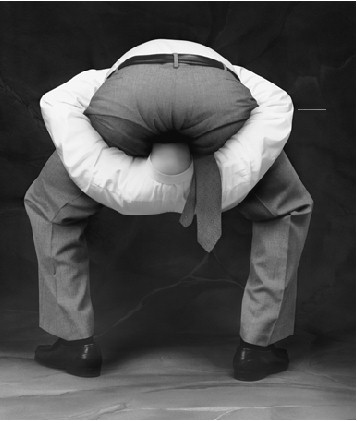

A low-carb diet "guru" hard at work examining the evidence for MAD.

Eades Breaks His Water

Eades ignores the fatal flaws of the Kekwick and Pawan study and instead starts ranting on about their insensible water loss data, ecstatically reporting that insensible water loss was greater on the high-protein and high-fat diets than on the high-carb diet.

Big bloody deal.

Insensible water loss is the amount of fluid you lose on a daily basis through evaporation at the skin and via the lungs. Insensible water loss is not a measure of fat loss. Again, body fat was never measured in the entire Kekwick and Pawan project. And despite what Eades would have you believe, insensible water loss is not a measure of metabolic rate, although it can indeed be affected by metabolism – along with such factors as ambient temperature, physical activity, and hydration status.

Eades mentions that taking thyroid or amphetamines, both of which increase metabolism, could increase insensible water loss. But to insinuate that low-carb diets could increase metabolic activity to anywhere near the degree of thyroid hormone or speed is patently ridiculous.

In a 1987 article on insensible water loss, Peter Cox from the Department of Anaesthesia, Motala Hospital, Motala, Sweden pointed out that:

"It has been estimated that there is a 13% increase in metabolism for every degree above 37°C. This increase in metabolism should therefore be associated with a similar increase in [insensible water loss], but in practice this does not seem to be the case. It is necessary to observe subjects in whom the metabolic rate can be varied under controlled conditions to be able to answer this question, a study that is hardly feasible. There may well be a relationship between metabolism and IWL over longer periods of time, but it seems hardly likely that IWL varies from day to day according to shortterm changes in metabolism, and this seems to be supported in the case of patients with temporary fever".[Cox]

In order to paint the hopelessly substandard Kekwick and Pawan study as supportive, Eades wants you to make a completely unfounded and unsupported assumption: namely, that increases in insensible water loss automatically equate to an increase in metabolic rate. But the evidence simply does not exist to support such a dubious leap of faith.

Indeed, when Kekwick and Pawan measured oxygen uptake in their subjects to calculate basal metabolic rate, they found no difference between the three diets. I repeat, they found no difference between the three diets. Eades simply ignores this, jumping instead on the fact that Kekwick and Pawan employed insensible water loss measurements because “it was considered that this might provide some indirect index of general metabolic rate”.

In other words, “Damn it, our most direct measurement of metabolic rate didn’t get the results we were after, so let’s see if we can tease them out with an indirect measurement of highly questionable relevance”.

Yeah, what an exemplary showcase of fastidious and detached research…

Kekwick and Pawan briefly flirted with reality when they wrote: “whether this increased rate of insensible loss is a measure of bodily metabolic activity must remain in question”. But they quickly slipped back into denial when they wrote: “Even if metabolic activity cannot be measured directly, the differences in weight responses seen with these diets does not seem to be completely due to an altered state of hydration or to a simple deficiency of calories.”

What a load of bollocks. Here we have a study in which cheating was rampant but we are earnestly supposed to believe that the differences in weight loss – never replicated by any other tightly controlled ward study before or since – were in fact due to a never-measured increase in fat loss caused by a non-existent increase in metabolism.

Yeah, sure thing…

In the insensible water loss segment of the Kekwick and Pawan experiments, a grand total of three subjects were weighed hourly on a highly sensitive scale and errors caused by variations in temperature, activity, and air draughts were avoided “as far as possible”. If the insensible water loss data of Kekwick and Pawan were accurate and not affected by confounding factors, then the only thing they demonstrate is that water loss through skin and lung evaporation is slightly greater on high-protein and high-fat diets. Woo-bloody-hoo! Again, I’m sure the ability to evaporate an extra thirty or so grams of water vapour each waking hour will no doubt thoroughly excite all those hapless folks who need to lose 100 lbs of fat!

Irrational leaps of faith are pretty much the bedrock of Eades’ entire MAD argument, but with the insensible water loss argument, he’s pretty much leaped into an even deeper pit of quicksand.

DING, DING, DING!!!

Well, that concludes the first round! We’re only a third of the way through the fight, but the frilly pink trunk-wearing Eades is already looking battered as he wobbles and staggers back over to his corner.

Round 2: Eades Wets Himself

The fact that cheating was able to occur to such a large extent in the Kekwick and Pawan study automatically renders the results extremely suspect. But let’s entertain Eades and his fellow MAD worshippers by ignoring the rampant cheating for now, and considering the total body water loss data from the Kekwick and Pawan study. The researchers made a big deal of the fact that the ratio of total body weight to body water loss allegedly remained constant among the participants on all the diets. According to Eades, this is proof that the alleged greater weight loss on the low-carb diets was primarily body fat, and not simply extra water. Eades makes this claim despite the fact that Kekwick and Pawan never even measured body fat changes. He instead assumes their water loss measurements were so accurate that they can be used to surmise the changes in body fat levels.

The Kekwick and Pawan study was conducted over 50 years ago. As usual, Eades is too blind to know why this would matter, but the truth is that available methodology and equipment for measuring body composition has come a long way since 1956. Things like near-infrared interactance, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), underwater weighing, and even skinfold calipers were nowhere near as widely used by clinical researchers as they are today.

But Eades doesn’t care about any of that. Kekwick and Pawan are telling him what he wants to hear, and he’s falling for it hook, line and sinker. But a look at the actual data in the Kekwick and Pawan paper quickly shows why Eades shouldn’t confuse sweet nothings with scientific fact. While the average ratio of water loss may have appeared constant, there was in fact wide variation among the reported percentage of weight lost as water among the individual participants. On the high-fat and high-protein 1,000-calorie diets, the ratio of weight lost as water ranged from 9-70% and 24-94%, respectively(Table IV). As for the total body water data on the high-carb diet…there is none. Kekwick and Pawan didn’t even bother to present it because the high-carb diet failed to produce any weight loss.

However, they did present the overall water loss data for twelve patients on the 1,000-calorie diets (Table IV). Again, there is wide variation in the amount of total body water lost, and there are two individuals who despite losing 1.8 and 3.6 kilograms of bodyweight gained 0.8 and 0.5 litres of body water, respectively. Because no increases in body water were observed during the low-carb diets, this increase in body water obviously occurred during the high-carb phase of the 1,000 calorie experiment.

I’ll let researchers from Denmark begin explaining the significance of these observations:

“The fact that Kekwick and Pawan’s obese patients temporarily maintained their weights on high carbohydrate diets yielding as little as 1000 calories (which is decidedly lower than the basal metabolism of a euthyroid adult) while others lost weight on high-fat diets containing as much as 2600 calories, seems to us to be the best indirect argument against Kekwick and Pawan’s main premise—namely, that the proportion of water in body-weight is unchanged. Their data reveal, not surprisingly, that some patients lost considerably less than the average 30-50% of the weight loss, while others augmented their total body-water content despite weight losses of up to 3.6 kg. In some the loss of water was much greater than the average, and in a few the water loss exceeded the loss of body-weight. This can only mean that the method of determining total body-water was too inaccurate to allow safe conclusions regarding fluctuations in bodily-fluid during short observation periods.”

The researchers who made these comments were Doctors Olesen and Quaade from the Nutrition Laboratory, 7th Department of Medicine, Kommunehospitalet in Copenhagen. They attempted to replicate Kekwick and Pawan’s findings over a longer time span, and in doing so showed why the Kekwick and Pawan results – along with all those who cite it as 'proof' of MAD – are a bad joke.

Olesen and Quaade examined eight obese females who consumed low- and high-carb diets in crossover fashion. Unlike the Kekwick and Pawan study where the “inadequate” subjects were free to roam around and scavenge food from trolleys, neighbouring wards and visitors, Olesen and Quaade’s patients “remained in hospital under strict control throughout the observation period”.[Olesen]

After an initial weight stabilizing period, the women were given high-fat diets containing less than twenty-five grams of carbohydrate per day. Two of the subjects consumed 1,500 calories of this diet daily. Their weights decreased during the next 5-7 days, then stabilized. During the next nine days when these 2 patients were given 2,000 calories of the low-carb/high fat diet, one gained a kilogram while the weight of the other did not change significantly.

A third patient was given the 2,000-calorie low-carb/high fat diet immediately after the weight maintenance period. This was in fact the same amount she ate during the weight maintenance phase. She proceeded to lose weight during the first five days before her weight stabilized. A similar pattern was observed in four other women who took the 2,000-calorie low-carb/high fat diet for 13 days.

Note the repeated pattern here: quick initial weight loss on a low-carb diet, followed by subsequent stabilization of weight. This is a pattern entirely consistent with a quick loss of bodily fluid due to the documented diuretic effects of low-carb diets[Yang]

During the last 5-7 days of the observation period all 7 women received around 1,250 calories in the form of a 60% carbohydrate diet, and their weights remained practically unaltered. Their basal metabolic rates showed that this calorie intake was less than their minimum energy requirements, which means the patients were indeed drawing on their energy stores (ie, adipose and possibly lean tissue) during this period. As the researchers pointed out: “The fact that their weights were unchanged can only be explained by water retention—possibly connected with glycogen storage”. They continued: “If as we think is inevitable, one assumes that the our patients retained water on this moderate carbohydrate intake, then it must follow that they were in a state of relative dehydration during the preceding period. The weight loss seen during the first 5-7 days of the fatty diet seems to reflect this dehydration. Thus the initial weight loss associated with the high-fat diet is not, in our opinion, due to a reduction of the fat deposits, and it cannot be termed “slimming” in the accepted sense of this word”.

The researchers weren’t just creatively opining – they measured oxygen consumption of the patients during rest and exercise, and used this to calculate energy metabolism. They found no difference between the high- and low-carb diets.

Astute readers will note there were eight women in this study but I have so far reported on the results of only 7. Before we discuss subject eight, let’s return back to the Kekwick and Pawan study. Along with the 1,000 calorie diets, the British researchers had also placed five obese patients on a 2,000-calorie diet containing “normal” proportions of protein, fat and carbohydrate. According to the Kekwick and Pawan, the subjects either maintained their weight or actually gained a little. When these subjects were then placed on a 2,600-calorie low-carbohydrate diet for periods ranging from 4 to 14 days, they allegedly lost weight. Eades again jumps on these findings and pronounces them as proof of MAD.

One minute Eades is back-pedalling and claiming he never said MAD is a big deal, that it only amounts to a difference of 100-300 calories. But now, as with the Liebel study, he’s using the Kewkick and Pawan study to claim a 600+ calorie-per-day metabolic advantage for low-carb diets.

In Part 1 of the Smackdown I pointed out that 630 calories is around the same number of calories an overweight adult male would burn pedaling vigorously on a stationary bike for 40 minutes[Ainsworth]. Eades wants us all to believe that merely by switching from a high- to a low-carbohydrate intake, we are able to increase our resting energy expenditure by a whopping 630 calories per day. Eades wants us to believe, in all seriousness, that simply by switching to a low-carbohydrate intake, the human body can magically start additionally burning the same amount of calories that would be expended during 40 minutes of strenuous exercise, each and every day.

I’m seriously starting to wonder if Eades has been hitting the morphine.

But let’s get back to subject eight in the Olesen and Quaade study. She was fed a 2,600-calorie diet, just like the Kekwik and Pawan study, which contained only 40 grams of carbohydrate. Unlike the Kekwik and Pawan study, she was administered the diet for nineteen days, a period longer than any of the durations employed by Kekwik and Pawan. In other words, a period longer than the woefully inadequate seven-day time span employed by Kewkik and Pawan in which the observed weight loss results were easily explained by fluid losses.

And guess what happened? During the first week, her weight dropped. If we were sleazy MAD shills, we’d stop the study right there, jump on the Internet, and write up a bullshit post gloating about the existence of a metabolic advantage. However, we’re not Eadesian wankers, and neither were Olesen and Quaade. Thankfully, they were much smarter than Kekwik, Pawan, and our dopey buddy Eades. They knew that Kekwik and Pawan didn’t keep their subjects on the diets long enough to give a true indication of whether the weight losses on the low-carb diets were merely greater fluid losses. In the case of subject 8, she was kept on the 2,600 calorie diet for almost 3 weeks. After her initial weight loss, subject eight began gaining weight despite continuing her constant 2,600 calorie intake. She finished the low-carbohydrate period heavier than when she began.

Read that again folks. She gained weight on the 2,600 calorie low-carb diet – as would all of the Kekwick and Pawan participants who required less than 2,600 calories per day had they stuck to the diet long enough. Once the initial diuretic effect of a hypercaloric low-carb diet stabilizes, the stockpiling of excess energy as fat starts to manifest itself on your scales (to all you researchers involved in physiology and biochemistry that are either laughing uproariously or shaking your heads right now at the fact that I need to even explain this stuff, you guys need to understand that people like Eades don’t live in the same world we do. We analyse the data in its entirety then come to our conclusions. Eades and his fellow MAD cohorts take the religious approach to knowledge acquisition – they start out with a cherished belief, and selectively seek out evidence to support that belief. When confronted with contradictory evidence they either ignore it, distort it until they think they’ve got it looking supportive, or defame the messenger by accusing him of being biased and corrupt. As we’ve seen, all three of these tactics are routinely utilized by the perennially shonky Eades).

That wasn’t the end of subject 8 ’s involvement. She also followed a high-carb diet (32% protein/18% fat/50% carbohydrate) for 24 days and a low-carb diet (32% protein/50% fat/18% carbohydrate) for 21 days. Energy intake during both diets was held at 1,000 calories per day. Just like the Kekwik and Pawan study. After 21 days on each diet the weight loss was exactly the same: 4.1 kg. Totally unlike the Kekwik and Pawan study.

What was that about me ignoring non-supportive evidence, Doc?

Water Loss on Low-Carb Diets is Real

Eades would have you believe that water loss in no way explains the differences in weight loss seen in the Kekwick and Pawan experiments.

A reader (Steinbach, again, you magnificent bastard 🙂 ) points out to Eades on his blog that the weight changes observed in the Kekwick and Pawan study could well be explained by the fact that low-carb diets exert a diuretic effect while high-carb diets exert a water-retaining effect. He reprints excerpts from two papers (which we will discuss below) that show high-carbohydrate diets simultaneously cause water retention, even while producing fat losses similar to isocaloric low-carb diets. When researchers only measure total body weight and ignore body composition, as Kekwik and Pawan did, then this gives the false impression that isocaloric low-carb diets are superior for weight loss.

Eades’ terse response to these MAD-destroying facts?

“I’m well aware of the water-retaining effects of dietary carbohydrates. And so were Kekwick and Pawan, who corrected for it in their study. A fact you would have known had you read the study.”

This appears to be Eades’ standard MO for dealing with the increasing number of dissenting readers at his blog – he evades their questions and instead snidely tells them they didn’t read or don’t know how to read the study in question.

Apart from his faithful followers, who may well constitute the most gullible and unquestioning readership in the entire nutrition arena, he’s not fooling anyone.

In reality, Kekwick and Pawan didn’t adjust for diddly. They never measured body fat, they never presented water loss data for the 1000-calorie high-carb diet, and they never discussed the various anomalies in their body weight and water data pointed out above by Olesen and Quaade and yours truly.

Eades’ dismissive answer also doesn’t even begin to explain why, when Olesen and Quaade attempted to repeat Kekwick and Pawan’s findings over the longer term, they couldn’t. Eades can’t claim to be unaware of the Olesen and Quaade study – it’s discussed right there in Chapter 1 of The Fat Loss Bible, which he’s spent the last 2 years of his life fuming over and desperately trying to “dismember” and “dissect”.

So let’s ignore the evasive pseudo-scientist that is Dr. Michael Eades and let’s see what real scientists have found when they examine the effect of low- and high-carbohydrate diets on bodily fluid balance.

A good place to start is an American Journal of Clinical Nutrition review by Walter Bloom[Bloom] that can be freely accessed here.

As Bloom notes, the water-retaining effects of carbohydrate are hardly recent news. In 1769, William Stark recorded a weight gain of over 3.5 kilograms (8 pounds) in only 5 days after changing his diet from meat to flour. Needless to say, no-one can gain that much pure fat in such a short amount of time.

This phenomenon of rapid water loss upon commencement of low-carb diets has been demonstrated repeatedly since. Bloom himself had observed that fasting (which naturally entails complete carbohydrate avoidance) produced a greater excretion of water-retaining sodium than that seen on a salt-free diet. He conducted a study in which obese participants were fasted while confined to a hospital. In nine of the patients, the fast was broken with glucose (150 grams) for the first 24 hours, after which a 600-calorie mixed diet (containing 44 grams of carbohydrate) was consumed. Some of the patients consumed a low-salt (200 mg/day) version of the diet while others consumed a higher salt (1000 mg/day) version. Another six patients broke the fast with the mixed diet, and the remaining 3 ended their fast with a pure fat/protein (zero carb) diet for 24 hours, followed by the mixed diet.

Among those who broke their fast with the 600-calorie mixed diet, “there was prompt and in some instances almost complete cessation of sodium excretion in the urine when food was ingested whether or not sodium was in the diet. In the patients receiving salt in the diet, the sodium excretion of fasting not only stopped but the patients retained the exogenous sodium. The same observation holds true for urine potassium, but the degree of potassium retention is not as great as that found for sodium. The weight loss of fasting promptly stops with the administration of 600 calories with or without sodium. Patients receiving salt may gain weight for several days despite hypocaloric intake. If the calorie restriction is continued, weight loss continues after a temporary readjustment period during which the weight gain was observed.”

The subjects that broke their fast with 600 calories of glucose also displayed prompt and in some instances almost complete cessation of sodium excretion. This pattern of salt retention continued when they commenced the 600-calorie mixed diet. Potassium excretion also diminished after glucose ingestion, but the decrease was of a much smaller magnitude than that of sodium.

However, the patients who broke their fast with the 600-calorie diet of fat and protein all promptly increased their sodium excretion and continued to lose weight. In the following 24-hour period, 600 calories of glucose resulted in a prompt and almost complete decrease of sodium excretion, which continued on the 600 calorie mixed diet[Bloom].

Bloom’s research shows that carbohydrates indeed have a very powerful effect on modulating sodium and hence fluid levels in the body.

Yang and Van Itallie demonstrated this in an even more lucid fashion. They took grossly obese male subjects and studied them in a metabolic ward for approximately 50 days each. During that time, they underwent three 10-day regimens: starvation, an 800-calorie ketogenic (10 grams carbs/day) diet, and an 800-calorie mixed (90 grams carbs/day) diet. To minimize possible order effects, the dietary regimens were imposed in counterbalanced sequence across subjects. Also, a 1,200-kcal (160 grams carbs/day) mixed diet was provided for 5 days before and after each experimental diet to reduce possible carry-over effects from the preceding regimen[Yang].

Before we discuss their findings, let’s take a quick look at the methodology they used to determine body composition changes:

“The composition of weight change was estimated from data obtained by means of the energy nitrogen (E-N) 2 balance method. This method utilizes the measurement of nitrogen balances to estimate changes in body protein content. If changes in body protein content are known, changes in body fat can be estimated from measurements of energy balance. Changes in body water are considered to be those changes in body weight not attributable to changes in body fat and protein…

We have compared the E-N balance method with those based on the measurement of total body water and total body potassium in terms of their ability to provide reliable data about composition of weight loss of subjects on weight reduction regimens. We have found that, when used in short-term studies, the E-N balance method yields data with substantially less variability than the data generated by the application of total body water [as used by Kekwick and Pawan] or potassium-based methods.”

OK, so what happened in the study? On the 800-kcal ketogenic diet, subjects lost a mean 466.6 g/day; on the isocaloric mixed diet, which provided 90 grams of carbohydrate daily, they lost 277.9 g/day. The composition of weight lost during the ketogenic diet was 61.2% water, 35.0% fat and 3.8% protein. During the mixed diet, the composition of weight loss was 37.1% water, 59.5% fat, and 3.4% protein.

The mean quantity (grams per day) of fat lost during the ketogenic diet was 163.4; during the isocaloric mixed diet, it was 166.7. Mean protein loss (grams per day) during the ketogenic diet was 17.9; during the mixed diet, it was 9.5.

The average contribution of body fat (percent of total calories) to the fuel mixture oxidized during the experimental regimens was calculated to be 97.2 during the 800-kcal mixed period and 94.4 during the ketogenic period.

In other words, “increased water excretion accounted almost entirely for the difference in rate of weight loss between the ketogenic and mixed diet periods”.

During the 5-day 1,200-kcal post-experimental periods, weight gains occurred after the 800-kcal ketogenic and fasting periods, and weight losses occurred after the 800-kcal mixed diet. In the period following the 10-day ketogenic diet, the rate of weight gain averaged 52.0 g/day, which was attributed to excessive water retention (180.6 g/day), in the face of continuing fat and protein losses (125.9 and 2.7 g/day, respectively).

After the 800-kcal mixed diet, an entirely different metabolic situation was observed. Weight continued to be lost, at a rate of 163 g/day, the composition of the loss being 3.7% protein, 73% fat, and 23.3% water.

It is noteworthy that during all three 1,200-kcal post-experimental periods (whether after fasting, ketogenic diet, or mixed diet), the mean rates of fat loss were almost identical (127.9, 125.9, and 119.0 g/day, respectively), despite major differences in loss of body water and small differences in nitrogen balance.

BMR was unaffected by the type of diet, as was the energy cost of physical

activity (lying, sitting, standing, and walking).

Again, Eades cannot claim to be unaware of the Yang and Van Itallie study because it’s cited in my book (and in Part 1 of The Great Eades Smackdown). He knows about it, but ignores it because it thoroughly blows the Kekwick and Pawan studies right out of the water.

Yang and Van Itallie clearly showed that ketogenic low-carbohydrate diets cause far greater water losses during a ten-day period (longer than the Kekwick and Pawan experiments) than non-ketogenic diets. That right there pretty much voids the entire Kekwick and Pawan claim to greater fat loss on their short-term low-carb diets. We also see from Yang and Van Itallie’s work that the switch from a ketogenic diet to a higher carb diet causes a prompt and transient increase in water weight that temporarily outweighs the continuing loss of body fat. In the Kekwick and Pawan studies, there was no stabilizing break period between the various diets. Their subjects simply went straight from one diet to another, amplifying the starkly contrasting effects of low-carb and higher-carb diets on water balance. To hold up the Kekwick and Pawan studies as 'proof' of allegedly greater fat loss capabilities of isocaloric low-carb diets is a total wank. Even forgetting about the cheating problem, their weight change results are fully explained by clinically demonstrated changes in water balance.

Eades would have you believe that water loss is not a factor in comparisons between low- and high-carb diets, but once again he’s spewing complete nonsense. The research shows it is unquestionably a very important factor. That’s why in chapter 1 of The Fat Loss Bible I don’t even bother with metabolic ward studies that lasted less than three weeks (except to debunk the much-hyped farce that was the Kekwick and Pawan study). I’ve never met an overweight person who achieved their fat loss goals in only a week or two, and these short-term studies are hopelessly confounded by the initial accelerated water loss that is typical of low-carbohydrate diets.

Eades, as usual, is full of it.

DING, DING, DING!!

That’s the end of round 2, and Eades is looking wobbly to the point of spasticity as he staggers back to his corner. As he collapses onto his ring stool his seconds, Gary Taubes and Richard Feinman, are frantically screaming at him: “You’re getting killed out there, Doc!! Do something for chrissakes, you’re making us all look bad! Distract him with your stinking keto breath…jab him with some Ketostix…blind him with some more bullshit…just do something…anyth-i-i-i-ng!!”

Round 3: Ripping Up the Utterly Non-Robust Findings of Rabast

During the late seventies and early eighties, West German researchers Udo Rabast and colleagues published the results of three metabolic ward trials that compared high- and low-carbohydrate diets. One of these studies found no significant difference in weight loss, but the remaining two allegedly found what no other metabolic ward study of similar duration has detected before or since - namely, statistically significant greater weight loss on a low-carbohydrate diet.

In one of their studies, obese inpatients following a high-carbohydrate diet supplying 1,000 calories per day lost 9.8 kilograms after 30 days, while those assigned to an isocaloric low-carbohydrate diet dropped 11.8 kilograms (another study presented in the same 1979 paper, comparing 1,900-calorie low- and high-carbohydrate diets, found no difference in weight loss). In the discussion section of their paper, the authors ignored the non-supportive results of the 1,900-calorie study and instead focused on the 1,000-calorie diet, claiming the results were most likely due to increased metabolism[Rabast 1979].

In a later study, subjects followed one of three different diets for 28 days, each providing 1,340 calories per day. Those following a high-carbohydrate diet lost 9.5 kilograms, while those following low-carbohydrate diets rich in corn oil or butter fat lost 11.4 and 12.5 kilograms, respectively. Again, the authors attributed the difference in weight loss to an increase in metabolic rate[Rabast 1981].

Eades loves the Rabast studies, claiming they offer “robust” evidence of MAD. He praises them for using “realistic” calorie intakes, but totally ignores the numerous other non-supportive ward studies that employed similar intakes. The truth is, the Rabast studies are about as robust as a wet paper bag. They are a jumbled mess of questionable methodology, self-contradictory data, and wholly unwarranted assumptions.

Let’s take a closer look at these discrepancies.

Unusually high and unexplained dropout rates. In contrast to most metabolic ward studies, where the high level of supervision and support is typically accompanied by very low or zero dropout rates, the two studies reported in the 1979 paper were plagued by unusually high attrition. A full forty percent of the participants in the low- and high-carbohydrate groups bailed from the trial, a significant anomaly for which no explanation was ever given. Just what exactly was going on in the metabolic ward over at the University of Wurzburg? Rabast et al won’t tell us (and whoever peer reviewed this paper must have been asleep on the job, because such high dropout rates demand an explanation and no journal worth its salt today would leave this discrepancy unquestioned).

Due to the high dropout rate, the results of the one supportive study in their 1979 paper wavered in and out of statistical significance. When the data for this study were tallied on day 30, they were statistically significant; 5 days earlier, they were not.

Failure to measure body composition. In their papers, Rabast et al insist that a metabolic advantage must explain the greater weight loss. Remember, the metabolic advantage concept is predicated upon greater fat loss, not muscle, glycogen, water, bone, or fecal losses. So if the researchers were confident that the low-carbohydrate diet elicited a metabolic advantage, they must have had data showing greater fat loss, right?

Wrong.

The researchers never even measured changes in body fat or lean mass, only total body weight. How one can assert a fat loss metabolic advantage without even bothering to measure body fat is a complete mystery.

In the 1979 paper that reported greater weight loss, Rabast and his team admitted they were unable to discount greater glycogen loss as a reason for the difference, but then proceeded to dismiss water or glycogen changes as possible causes of the greater weight loss any old how. Total body water was not measured in any of their studies. Among the 117 subjects of their 1979 report, they did not measure fluid balance nor urinary excretion of sodium or potassium except in “some patients on diet 1” (the 1,000 calorie diet).

What the…? Exactly how many of the twenty-eight patients who completed diet 1 (of the 45 of who commenced it and dropped out for unknown reasons) is “some”? Ten? Five? Two?

No answer.

And of the “some” patients who were measured, did they stick around for the entire study, or were they among the many that headed for the door while the study was still in progress?

From this totally unknown quantity of patients, Rabast et al tell us that urinary excretion of sodium and potassium did not differ “significantly” on the two diets and they prove this by failing to present any potassium and sodium data whatsoever.

So here we have a couple of studies consisting of a very half-assed attempt at gathering fluid data, extremely sketchy information about sodium and potassium excretion, and no attempt whatsoever to measure body composition…being used to support a fat loss metabolic advantage and to dismiss the possibility of greater sodium, potassium, glycogen and fluid losses on the low-carb diet.

Only a myopic MAD shill like Eades could love a study like this.

Scientifically untenable claims of “increased metabolism”. In the 1979 study that reported greater weight loss, Rabast and his team claimed "…an increased rate of metabolism presents itself as the most feasible explanation." This despite the fact they never measured metabolic rate in any of the participants.

As we learned in Part 1 of the Smackdown, an increased rate of metabolism is not a feasible explanation for the findings. Tightly controlled studies have repeatedly shown absolutely no increase in metabolic rate or dietary-induced thermogenesis (DIT) for low-carb diets or meals.

Sodium, glycogen and water loss would constitute a far more realistic explanation for the findings of Rabast and his team. Glycogen is the form of glucose that is stored in muscle and organs, and is often diminished on low-carbohydrate diets. Similar to sodium, loss of glycogen causes considerable water loss, as every gram of glycogen is bound with 3-4 grams of water.

In their 1981 study, Rabast et al decided to lift their game a little, measuring urinary sodium and potassium not just in “some” but all of the twenty-one participants. This far more thorough approach revealed significantly greater sodium excretion during the first week and significantly greater potassium excretion during the first three weeks of the corn oil-rich low-carbohydrate diet and the first two-weeks of the butterfat-rich low-carbohydrate diet. For the remainder of the study, this higher potassium excretion persisted “even after 28 days”, but the higher rate of excretion during this remaining time failed to attain mathematical statistical significance.

As noted, a considerable amount of the potassium inside our bodies is bound up with glycogen, so the greater potassium losses in Rabast's low-carbohydrate dieters are likely a reflection of greater glycogen and hence water losses.

The researchers, and Eades, make a big deal of the fact that this potassium excretion had diminished by the end of weeks two and three on the butterfat- and corn oil-rich low-carbohydrate diets. But so what? The damage had already been done. The low-carb dieters had already shed a greater amount of glycogen and were now maintaining lower bodily glycogen and fluid levels than the high-carb dieters. Once depleted, glycogen levels do not magically restore themselves on a low-carbohydrate diet – that does not happen until a higher carbohydrate intake is restored.

Ignoring the very real potassium depletion caused by the low-carb diets is like observing a riot and then pretending it never happened after the police have restored law and order, even though the streets are still littered with charred and broken evidence to the contrary.

The Rabast studies were not performed in concurrent crossover fashion, so the German researchers were unable to present data showing what would have happened to the low-carb dieters when they reverted to an isocaloric high-carb diet, so I’ll tell you what would have happened based on years of clinical and empirical observations: they would promptly have gained water weight as their muscles restocked with glycogen and fluid (to all you weight trainers who wonder why your muscles promptly look bigger, healthier and fuller after switching from a low-carb diet back to a high-carb diet, that’s glycogen replenishment in action right before your very eyes).

Proof of this comes from Cambridge University researchers, who realized that utilization of glycogen stores during weight reduction has a significant effect on apparent weight loss and the degree of weight regain after a period of dieting[Kreitzman]. They placed eleven female subjects on the very low-calorie (400 cal/day), low-carbohydrate Cambridge Diet for 10 weeks. Four days before starting the diet, total body potassium was measured in each subject, then assessed again on the fifth day and at the end of the 10-week program. Potassium decreased during the first four days of the diet by 180 mmol compared with only 104 mmol lost in the subsequent 10 weeks of dieting. Because 0.45 mmol potassium represents 1 gram of glycogen, the researchers estimated a mean loss of 400 grams of glycogen in the first five days of the diet, with individual losses ranging from 80 to 1,066 grams.

In their summary, the researchers noted that glycogen “losses or gains are reported to be associated with an additional three to four parts water, so that as much as 5 kg weight change might not be associated with any fat loss. As glycogen stores are readily replenished after conclusion of any weight-loss program, it is necessary to account for these losses before comparing effectiveness of weight-loss methods" [emphasis added for the benefit of our buddy Mike and his clueless MAD chorts].

Similar to the Kekwick and Pawan findings, no-one has ever been able to confirm the conclusions of Rabast et al. Eades praises the “realistic” level of the 1,000 calorie diet in Rabast’s 1979 paper, but makes no mention of the exact same caloric level when employed in the non-supportive Olesen and Quaade study. He also makes no mention of a study by Pilkington and colleagues at St Georges Hospital in London that also used 1,000-calorie diets. Unlike the sloppy Kekwick and Pawan study that Eades so eagerly cites, where the patients were free to roam neighboring wards and scavenge extra food from trolleys, other patients, and visitors, the Pilkington study “was carried out in the metabolic unit, where the patients were isolated from the general ward population.” The study involved seven women and 2 men, all obese. The two male patients and 2 of the females followed 800-calorie low- and high carbohydrate diets in crossover fashion for 18 days each, while the remaining women followed 1,000 calorie low- and high-carb diets for 24 days each.

The patients alternated from one diet to the other, with two of the patients spending a total of 48 days on each diet. No significant difference was noted in the rate of weight loss, although the researchers did observe short, transient increases in bodyweight upon commencement of the high carbohydrate diet phases. These increases of up to 2.5 kg would last up to 10 days before disappearing, at which point weight loss would continue on a downward trajectory. The researchers measured fluid balance during the study, and noted that the temporary swings in weight could be explained not by greater fat losses, but by variations in fluid status. Lean tissue, primarily muscle, is the primary storage site for glycogen. Indeed, Pilkington and his team noted greater nitrogen losses on the low-carb diets, indicative of greater lean tissue losses[Pilkington].

Commenting on the sloppy farce that is held as the gold standard of MAD research by sleazy low-carb shills, Pilkington et al noted: “Kekwick and Pawan (1956) showed similar swings and attributed them to changes in the metabolic requirements of their patients on different diets, but they produced no evidence of these changes.” [again, emphasis added for the benefit of Dr. Michael Eades and his not-so-bright MAD mates]

As evidence for the metabolic advantage theory, the Rabast studies are about as “robust” as a wet noodle. Their studies are a showcase of incomplete reporting, questionable methodology, and unwarranted assumptions. Their results are easily explained by greater glycogen and fluid losses.

BOOM!

THUD!

[Sound of pink-trunk wearing diet guru copping a knockout shiner and hitting the canvas]

DIING, DING, DING!!

“Ladies and gentlemen, the winner of this evening’s bout by knockout…scientific reality!!”

[Deafening cheers and roars of approval from crowd]

Popping Off More Irrelevant BS

Eades is a keen practitioner of the “if you can’t dazzle them with brilliance, blind them with bullshit” dictum. This battle of bad blood between myself and the grey-haired one has been dragging on for over 2 years. In that time, I have repeatedly requested that Eades and his demented MAD followers justify their abundant hostility and hyperbole with some actual tightly-controlled human evidence showing greater fat loss – not water, fecal, bone or lean mass losses - on isocaloric low-carbohydrate diets. At one point I even issued a $20,000 challenge to these schmucks, but even that failed to draw out a single supportive study.

The simple truth is that they do not have any such evidence.

Eades is back to waffling on about Karl Popper, a tactic he unsuccessfully tried two years ago. Of course Eades has hit the depths of desperation, and is not above dredging up past material in an attempt to save face.

According to Eades, Popper’s dictum that you only need one non-supportive study to disprove a hypothesis can be applied to support MAD. According to Eades, only one non-supportive study is all that is required to disprove the well-accepted fact that varying the carbohydrate content of isocaloric, isoproteinic diets has absolutely no discernible effect on fat loss.

There’s just one wee problem with this contention – as we have seen, Eades and his MAD cohorts do not have a single tightly controlled study showing greater fat loss on an isocaloric low-carb diet.

Eades’ citation of Popper is just a copout, pure and simple. It’s a thinly veiled smokescreen he is using in order to avoid having to discuss the large volume of research that in fact shows MAD to be a complete sham.

What Eades is really saying when he waffles on about Popper, white swans, black swans, blahblahblah is: “I don’t have a hope in hell of refuting all the evidence Colpo has presented, so I’ll get him with a red herring that allows me to simply ignore it.”

The red herring being the claim that only one non-supportive study is required to disprove a hypothesis. But there are a couple of important qualifications to this claim that Eades conveniently ignores.

1. The non-supportive study must be a high-quality one in which the results can reasonably be assumed to have not been influenced by design flaws, inappropriate participant behaviour (for example, cheating), or incompetence or impropriety on the part of the researchers conducting and reporting the study.

2. The results of said study must be able to be replicated by other researchers. If you, as a researcher, claim to have attained a finding, but other researchers who replicate your study in a similar - or superior – study repeatedly fail to confirm these findings, it usually means one thing: your findings were bullshit.

A classic example of this was the “calcium and dairy cause fat loss!” charade that occurred several years ago. It all started when a group of researchers fed a bunch of subjects dairy products and observed that they lost more weight than those who didn’t get the extra dairy. Overnight, the nutrition arena was rife with claims that dairy and calcium supplements could help you lose weight. The dairy industry even began a promotional campaign based on the results of this study.

Unfortunately, the results – although peer-reviewed and published in a reputable journal – were untenable. When other researchers went looking for a fat loss effect of dairy and calcium, they repeatedly failed to find it. Heck, even a subsequent study by the same group of researchers failed to confirm the results of the original study. The fat loss claims for calcium and dairy foods started to peter out, and the FTC ordered the dairy industry to cease and desist with making unfounded fat loss claims in their advertisements.

So just because a study disputes a hypothesis, that doesn’t even begin to disprove the hypothesis. The reality is that there could in fact be dozens of non-supportive studies, but if they exhibit the flaws described in points 1 and 2 above, then their impact on the hypothesis is nil.

For a study to disprove a hypothesis, it must be of high quality and its results must be able to be confirmed by other researchers. The two examples Eades cites – the Kekwik/Pawan and Rabast studies – fail miserably on both counts.

The Sad Parody That Is Dr. Michael Eades

The hypocrisy of Eades is absolutely astounding. Listen to the old prat as he jumps on his high horse and lectures others about negative traits of which he himself is incurably affected:

“Many scientists don’t want to hunt for black swans, however, because they don’t want to blow up their hypotheses. The easy way to bolster their hypotheses is to continue to tally up all the white swans they find and forget about looking for black ones.

Which, of course, is what our young friend AC has done and written about in his latest missive. He tallies up a bunch more white swans and ignores the black ones, even the black ones in hiding in plain sight in his own list of papers. This failure of his to try to puncture his own hypothesis leads me to believe there exists a large chasm of incomprehensibility between the way AC thinks and the scientific method."

In my book The Fat Loss Bible, I report the results of every metabolic ward study I could find lasting three weeks or more. No-one, I repeat no-one in the MAD camp has ever bothered to do this. They are quite content to simply cherry pick garbage studies that appear to support what they want to believe.

In Part 1 of the Smackdown, I presented several tightly controlled studies showing absolutely no increase in metabolism or DIT from low-carb diets or meals. I actually have more such studies in my files, and they all show the same thing. The grand total number of studies Eades has presented that compared metabolism or DIT on low- versus high-carb diets? A big fat zero.

He then accuses me of ignoring “black swans”.

Eades, you're a dick.

Futile Cycles and an Elephant’s Ass

Eades’ began the first of his three attempted rebuttals to Part 1 of my Smackdown by rambling on about “futile cycles”, which is quite appropriate given that his quest to defend MAD is one big futile attempt to save face whilst drowning in a sea of his own bullshit.

In his initial response, Eades also posts a picture of someone looking at an elephant’s ass, while in his second response, he posts a picture of a young child being hypnotized, continuing his long tradition of prefacing MAD articles with pictures that have absolutely nothing to do with MAD. I can just picture Eades as he posts these pictures, guffawing so hard at his own cleverness that he momentarily loses control of his bladder function and stains his diapers, but the reality is that crappy segues using totally irrelevant photographs don’t even begin to hide the indisputable fact that Eades still has no tightly controlled evidence for a fat loss metabolic advantage of low-carb diets.

Nothing has changed: MAD is still a sham, and Eades still has nothing in the way of tightly controlled evidence to dispute this.

What do these pictures have to do with MAD? Absolutely nothing.

Just like pictures of educational software, a kid being hypnotized,

an elephant’s ass, and Youtube parodies of ‘roid raging bodybuilders –

all of which the dimwitted Dr. Michael Eades has posted in his

bizarre attempts to discredit me.

Good on you Doc, I guess you really showed me!

My Farewell to Dr Sleaze

Eades finishes his March 10 bullshit-fest with more of his usual deluded self-praise, this time dressed up as a thinly disguised tribute to yours truly:

"So, to you, Anthony Colpo, I raise my hat. Had you not attacked me out of the blue, I would be less knowledgeable than I am today. I wouldn’t have bothered to dig into all the ‘white swan’ papers you posted trying to figure out why these researchers got the results they got. I, like you, would still be mired in the notion that metabolic ward studies are squeaky clean without any hint of sullied data as a consequence of cheating. Like you, I would still probably be confusing metabolic ward studies with metabolic chamber studies, which are horses of a much different color. Also, I thank you because I had kind of blown off the Kekwick and Pawan papers (there are others besides this one from The Lancet) as being too old to be worth studying. You forced me to take another look, and I was delighted at what I found. And, sad to say, like you, I, too, had read only the first part of the these studies, the parts about the diet comparisons. It wasn’t until your attack that I actually read this paper all the way through and found the gold mine in the latter pages.

So, AC, I sincerely hope the best for you; I thank you for pushing me into this exercise and wish you godspeed on your journey through life."

I wish I could say the same, that Eades was a worthy opponent who challenged me and pushed me to new heights of knowledge. But the truth is that I cannot view Eades as anything other than a dishonest intellectual featherweight. Throughout this entire debate, he has showed no interest whatsoever in objectively examining both sides of the argument before settling on a conclusion. He boasts about his new swan-enhanced state of enlightenment, but the truth is that Eades hasn’t learned shit – at least not when it comes to nutrition and fat loss. The only thing Eades has truly learned from our exchange is how to more effectively evade reality and shove his head even further up his ass.

For Eades, this entire exercise has been about vigorously avoiding the truth, no matter what degree of patently absurd mental contortionism is required. Eades appears to be a scared little man who simply cannot even begin to fathom the consequences of having to re-examine his beliefs. Instead, he does what all dogmatists do - he clings to his cherished beliefs come hell or high water and embraces only supportive evidence, avoiding contradictory evidence like he's violently allergic to it. When forced to confront contradictory evidence, he simply rolls out the hogwash and claims it says and show things that it clearly doesn't.

Throughout this whole exchange, he has repeatedly accused me of lying, of being deceitful, of selectively citing evidence. They’re fighting words, but I guess any little weasel can talk smack from the safety of his computer screen, thousands of miles away.

Dr. Michael Eades, how about you put your money where your big arrogant mouth is, and show me exactly where are the studies I allegedly ignored? Where on Earth are the tightly controlled studies showing metabolic rate or dietary induced thermogenesis to be greater on isocaloric low-carb diets/meals? Where on Earth are the tightly controlled studies with real live humans showing greater isocaloric fat loss on low-carb diets? I'm not interested in mice or rat studies where increases in metabolism due to the effects of a diet that rodents were never meant to eat explain the greater fat losses. As the research clearly shows, these low-carb-induced increases in metabolism simply do not occur in human beings.

So where is the human evidence, oh grey-haired one?

You and I both know the answer to that: it doesn’t exist.

The big mistake that Eades, Atkins and the rest of the MAD movement made is that they got way too excited from the findings of greater weight loss on low-carb diets in free-living studies. They were totally ignorant of the very real and well documented role that dietary underreporting plays in such studies. As such, they never bothered to stop and gather up all the metabolic ward evidence in its entirety to see what that showed before spouting their MAD mouths off.

Eades' further folly is that he has a long history of sneering and snickering at all those he disagrees with, and he's proven that he's not above acting like a defamatory misogynistic pig to get his point across. Unfortunately, his luck ran out when he weighed in on the MAD debate with a totally absurd and intellectually dishonest comparison of two totally incompatible studies, then capped it off by saying that anyone who thinks fat loss is all about calories is a "fool" and that I was wrong on the MAD issue. After two years of putting up with virulent hostility from his demented low-carb cohorts, I'd had enough. It was time to beat the MAD crowd over the head with their own bullshit.

So let that be a lesson folks. I didn't attack Eades “out of the blue”...he simply experienced the inevitable outcome of being an arrogant serial bully. You go shooting your mouth off around town, and sooner or later you're going to front up to someone bigger, smarter, and more tenacious. And when that happens, you'll get your ass kicked.

Just like what happened to Dr. Michael Eades.

Gimme a Ten-Speed, Not Godspeed

Eades, in his pious pseudo-tribute, wishes me “godspeed” (a Christian substitute to the allegedly sacrilegious "good luck"). Thanks Eades, but you're the one who needs all the luck he can get. Good luck with continuing to get up every morning and having to do something I've never had to do: look in the mirror and see a reality-evading sham staring back.

If there’s one thing that’s more important than all the money in the world, it’s the ability to be at peace with yourself in the knowledge that you are a man of character and a man who speaks the truth - no matter how 'controversial' and unpopular that may make you in certain quarters (including the low-carb portion of the Internet, a bizarre world filled with rotund blogging wankers and forum-inhabiting losers, all of whom need to push themselves away from their damn computer screen once in a while and get themselves a fucking life). No Lamborghini or poncey overpriced painting is worth more than a person who respects and values the facts far above the transient brain-dulling sense of relief that comes from avoiding reality. That kind of respect, Eades, is a feeling you may never know, and for that I truly pity you.

Conclusion

The highly hyped metabolic advantage of low-carb diets does not exist, which no doubt is a big reason why the popularity of these diets peaked in 2004 and has been declining ever since (another major factor appears to be that people simply find these diets, like the one-dimensional sods that promote them, to be boring) [Warner]. That’s why Eades’ latest book is selling poorly despite, on paper, having every reason to succeed – i.e. promises of quick weight loss from authors with a previous bestseller and the backing of a large publisher.

As a diet ‘guru’, Eades’ time has come and gone. The future of weight loss belongs to those who understand that a calorie deficit achieved by exercise and/or calorie restriction is the key to weight loss, and that there are numerous dietary routes to this goal. Despite what low-carb dogmatists wish to believe, many people successfully lose weight on high- and moderate-carbohydrate diets. Whatever diet one chooses to follow should be based on the diet that is most appropriate for their personal preferences, health requirements, lifestyle and convenience considerations, and activity levels. Cultural factors also need to be considered here (try telling overweight Japanese they should stop eating rice or obese older Italians to avoid pasta…good luck with that!). Wherever possible, this choice should be made in conjunction with information disseminated by non-partisan commentators with a scientific orientation, not blatantly biased diet shills whose primary concerns are PR and profits.

My prediction is that the very low-carb and low-fat paradigms will continue to fall by the wayside, as people continue to gravitate toward the middle ground, where fresh meats and produce and low-glycemic, evolutionary-correct carbohydrate sources abound.

To view Part 1 of The Great Eades Smackdown, click here.

References

Kekwik A, Pawan GLS. Calorie intake in relation to bodyweight changes in the obese. Lancet, Jul 28, 1956; 271 (6935): 155-161.

Olesen ES, Quaade F. Fatty Foods and Obesity. Lancet, 14 May 1960; 275 (7133): 1048-1051.

Cox P. Insensible water loss and its assessment in adult patients: a review. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 30 Dec 2008; 31 (8): 771-776.

Bloom WL. Carbohydrates and Water Balance. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Feb 1967; 20: 157-162.

http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/reprint/20/2/157.pdf

Bloom WL. Inhibition of Salt Excretion by Carbohydrate. Archives of Internal Medicine, 1962; 109: 26-32.

Yang M, Van Itallie TB. Composition of Weight Lost during Short-Term Weight Reduction. Metabolic responses of obese subjects to starvation and low-calorie ketogenic and nonketogenic diets. Journal of Clinical Investigation, Sep 1976; 58: 722-730.

http://www.jci.org/articles/view/108519/pdf

Rabast U, et al. Dietetic treatment of obesity with low and high-carbohydrate diets: comparative studies and clinical results. International Journal of Obesity, 1979; 3 (3): 201-211.

Rabast U, et al. Loss of weight, sodium and water in obese persons consuming a high- or low-carbohydrate diet. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism, 1981; 25 (6): 341-349.

Kreitzman SN, et al. Glycogen storage: illusions of easy weight loss, excessive weight regain, and distortions in estimates of body composition. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1992; 56: 292S-293S.

http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/reprint/56/1/292S.pdf

Warner M. Is the Low-Carb Boom Over? New York Times, Dec 5, 2004. Available online here.

Comments and questions from readers are always welcome, but due to time constraints a response cannot be guaranteed. If you find lack of response to your correspondence offensive, please don’t write. Emails with offensive, argumentative, hostile or generally imbecilic content will be ignored.

Anthony Colpo is an independent researcher, physical conditioning specialist, and author of the groundbreaking books The Fat Loss Bible and The Great Cholesterol Con. For more information, visit TheFatLossBible.net or TheGreatCholesterolCon.com

Copyright © Anthony Colpo.

Disclaimer:

All content on this web site is provided for information and education purposes only. Individuals wishing to make changes to their dietary, lifestyle, exercise or medication regimens should do so in conjunction with a competent, knowledgeable and empathetic medical professional. Anyone who chooses to apply the information on this web site does so of their own volition and their own risk. The owner and contributors to this site accept no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any harm, real or imagined, from the use or dissemination of information contained on this site. If these conditions are not agreeable to the reader, he/she is advised to leave this site immediately.