Low-carb diets have never gained a foothold in professional sport for one simple reason; professional athletes are expected to perform consistently at a high level. Their very livelihood depends on it.

If their performance suffers, all hell breaks loose. Sports columnists start writing savage critiques, fans start calling for their heads, sponsors start wondering whether they should continue with lavish endorsements, and team selectors start sizing up other promising athletes as potential replacements.

So, apart from the occasional wayward athlete, low-carbohydrate diets are avoided like an infectious disease in the upper echelons of sport. Given that they’ve been repeatedly shown to kill performance in glycogen-dependent activities, it’s little wonder that top-flight athletes and their coaches avoid them like a bad smell.

Unfortunately, low-carb propaganda has swayed many amateur athletes and serious recreational exercisers who don’t enjoy the same professional advice available to elite athletes. As we learned in Part 1, these folks have been duped into believing the fallacious “fat adaptation” myth. Because they don’t have the kind of professional, financial and social pressures that would promptly terminate any elite athletic dalliance with low-carbing, many non-professional athletes have adopted these diets then struggled along in a state of denial, often for years on end.

If that’s you, then my advice is to have a change of clothes ready, because Coach Anthony is about to pour a big bucket of ice cold water over you and finally snap you out of your low-carb stupor.

Fat Adaptation and Other Low-Carb Fairy Tales

In order to justify use of a diet in athletes that science has repeatedly shown to be a complete crock, low-carb authors and Internet ‘gurus’ use a mix of pseudoscience and selective citation to support their case.

Let’s start with a study frequently cited by the fat adaptation believers, which examined the effect of a ketogenic diet in six moderately obese, untrained subjects. Stephen Phinney and his colleagues placed them on a zero-carb diet of lean meat, fish, or fowl for six weeks, supplemented with minerals and vitamins and providing 500-750 calories per day. At the start of the study, the subjects performed a treadmill endurance test with a mean workload of 76% VO2 max and a mean time to subjective exhaustion of 168 minutes. After six weeks, the subjects lost a mean 10.6 kilograms, were able to perform the test at only 60% VO2max, a lower heart rate, and a mean time to exhaustion on the treadmill of 249 minutes[1].

Wow, a performance increase of 81 minutes, simply by eliminating carbohydrates! Damn, I’m throwing out the noodles, changing my last name to Atkins-Moore-Dukan-Eades, and quitting my job to become a professional power-walker! London 2012, here I come, baby!

Oops, hang on a minute. I think I see a few problems with this study. Do you see them too?

--The study involved untrained and very unfit subjects. So the improved results at the end of the study could simply have been due to improved fitness and acclimation to the walking test, not to any special "fuel-mobilizing" effect of the low-carb diet;

---The tested activity was walking, which is about as low intensity a physical activity as they come. The lower the intensity of the exercise, the less of a factor glycogen depletion will be. But the fact remains that the fitness gains conferred by walking are limited, and most sport activities require a far higher level of exertion;

---There was no high-carbohydrate control group. How on earth can this study be used to argue for the comparative benefits of low-carb nutrition in physical activity when there was no comparison diet?

For someone to have to work at over 70% VO2max simply from walking indicates very poor starting fitness. Once the subjects experienced initial adaptation and fitness improvements, the intensity of the exercise was not increased commensurately. So what would have happened if the subjects were forced to keep performing at a higher level of VO2max, rather than the leisurely 60% that was observed in the second treadmill session?

What would have happened if there had been another group in the study following a high-carbohydrate diet?

These questions were addressed by a subsequent study also conducted by Phinney and co. This time, eight untrained, obese females followed either a zero-carb diet or a carbohydrate-containing diet for 6 weeks. Both groups ate lean meat, fish, or fowl. Margarine was given to the zero-carb group for extra fat, while the carb group received grape juice supplying seventy-five grams of carbohydrate daily. Both groups consumed 830 calories per day.

Unlike the previous study, the subjects performed their endurance tests on a stationary cycle. And unlike the previous study, the initial VO2max target was maintained for all subsequent tests. After one week, endurance at around 75% VO2max dropped by a whopping 50% in the zero-carb group - and that's where it stayed for the rest of the study. In contrast, the carbohydrate group experienced no change in their endurance performance. Glycogen levels in the thighs of the zero-carbers also plummeted by half, but remained unchanged in the carbohydrate group. Despite their markedly different carbohydrate intakes, both groups showed similar levels of ketones throughout the study (the minimum threshold for ketosis rises in vigorously exercising individuals, as we'll discuss shortly). Rather than ketosis, the decline in endurance was highly correlated with the decrease in muscle glycogen stores[2].

Astute readers may be thinking: “OK Anthony, this study shows that zero-carb diets suck dirty workout socks when it comes to exercise, but 75 grams doesn’t exactly constitute a high-carb diet, either!”

Very good, my observant little grasshoppers. But remember, obese people are carrying a lot more body fat to use as fuel than their lean counterparts, and they tolerate severe calorie restriction far better, losing less lean tissue in the process. For lean folks engaged in regular strenuous exercise, a daily carbohydrate intake of seventy-five grams is nowhere near sufficient, as we’ll find out shortly.

Sprinting to Hell on a Zero-Carb Diet

Before we do that, let’s take a look at another study cited ad nauseum to support low-carb diets, this time involving a group of individuals participating in a sport dear to my heart: road cycling. According to the hyperbolic purveyors of low-carb bollocks, this study showed that four weeks on a zero-carb diet did not impair cycling performance.

Within seven to ten days of cutting carbs to zero, the cyclists experienced the well-known transient energy “crash” many folks experience soon after starting a ketogenic diet. During this time, the cyclists felt like crap and had trouble keeping up their training schedules. This passed, and after four weeks no decrease in endurance was allegedly noted when they were tested at 62-64% VO2max.

Cool. No carbs, no drop in performance! Who needs all that rice and post-workout dextrose, anyhow? I’m gonna start having me some whipped cream after a hard ride!

Oops, hang on - oh no, not again – another great-sounding result that’s not what it seems. Dammit, this always happens when I read the full text of a study for myself instead of believing the second-hand hogwash on Internet forums! Within minutes, I discover that someone’s been yanking our chains.

And so it is with the cyclist study. Here’s what you haven’t been told: While the performance of the cyclists at 62-64% VO2max was reportedly unaffected by the ketogenic diet, Phinney (also the head researcher of this study) admitted years later that their ability to perform more intense activity (sprinting) deteriorated[3]. Phinney, (a pro-low-carbohydrate commentator who recently co-authored an Atkins diet book with Atkins-sponsored researchers Eric Westman and Jeff Volek[4]), described the sprinting performance of the ketogenic cyclists as “constrained”.

That’s a rather subdued way of saying “their sprinting performance went down the toilet faster than a batch of amphetamines when the police knock on the door of an outlaw biker clubhouse”.

Telling a competitive cyclist that a zero-carb diet won’t affect his ability to perform moderate endurance exercise but his sprinting ability will be “constrained” is a bit like telling a bloke that lopping off his manhood won’t affect his general mobility but will “constrain” his sex life.

Hmmm, given that most cycling races are won only after a frantic sprint to the finish, the correct conclusion from Phinney’s study would be: “Zero-carb diets are pretty much useless for competitive cyclists”. In fact, they’d be useless for any sport that includes both an endurance component and short bouts of explosive activity which is like, um, almost every popular sport in the world.

It’s at this point that the low-carb shills will interject and complain that the cyclists’ poor sprint performance was due to a lack of fat adaptation. The cyclists needed longer to become fat adapted, bro, and then their performance would have been fine, man!

Yeah, right. And if you lob off a guy’s manhood, it will magically grow back if you wait long enough.

As we have already discussed, the subjects experienced the customary initial energy crash that frequently accompanies the fat adaptation process. This was accomplished within ten days, right at the start of the study. By the end of the four week study, the subjects were well and truly fat adapted, a fact confirmed by respiratory quotient (RQ) testing. Measuring RQ allows researchers to check how a person's fat adaptation is coming along, and is typically expressed on a scale ranging from 1.0 (pure carbohydrate oxidation) to around 0.7 (pure fat oxidation). At the completion of the study, Phinney’s elite cyclists displayed a mean RQ during testing at 60-65% VO2max of 0.72 – which is a bee’s cajone away from 0.7[5]. In other words, they were as “fat adapted” as they were ever going to be.

And that’s not all folks. The study abstract concluded “aerobic endurance exercise by well-trained cyclists was not compromised by four weeks of ketosis”. But even at the lower intensity used in this study, two of the cyclists did in fact experience significant declines in their time to exhaustion (-48 and -51 minutes). Another experienced a 3-minute increase, while two others experienced a 30-minute and a whopping 84-minute increase. Calling hogwash on a published finding is never a pleasant job, as it causes the individuals involved to develop a deep dislike of yours truly and purchase Anthony Colpo voodoo dolls that they then angrily stab repeatedly, causing me to experience inexplicable shooting pains in my torso when I’m sitting with my buddies watching The Wanderers for the 576th time.

Nonetheless, as your fearless caller-outer-of-hogwash, that’s exactly what I’m going to do here. No other controlled study supports the claim that any healthy, well-trained, weight stable individual who switches from a high-carbohydrate diet to an isocaloric ketogenic diet will increase his time-to-exhaustion by a massive 57%. So why would this study have found such a thing?

Let’s take a look at the way the study was performed. During the first week of the study, the cyclists consumed a high-carbohydrate diet supplying enough calories to keep their weight stable. The next four weeks were spent on an isocaloric zero-carb diet that also resulted in no weight change. At the end of weeks one and four, the cyclists performed their endurance tests. Unlike other studies, there was no familiarization test and the tests were not performed in random order. Everyone performed the first test after one week of the eucaloric high-carb diet, then the second test after four weeks of the zero-carb diet. Therefore, the improved performances may simply have been an artifact of test familiarization; that is, improved efficiency as a result of a learning effect when performing an unfamiliar test for the second time. As Andrew R. Coggan, Ph.D, an exercise physiologist, multi-sport endurance athlete and prolific published researcher, noted: "in my opinion, and those of many others, such large changes in performance are not believeable, suggesting that the pre-diet performance of [the cyclist who experienced an 84-minute increase] was greatly underestimated"[6].

So what we have from Phinney’s study is sprinting performance that promptly went down the crapper, worsening endurance performance in 2 of the cyclists even at low exercise intensity levels, no significant change in another of the cyclists, and extremely unlikely increases in “endurance” in the remaining 2 that are most likely an artifact of test familiarization. This, ladies and gentlemen, is the pinnacle study from which we are supposed to conclude that low-carbohydrate dieting will not hurt endurance cycling performance.

Thanks guys, but I think I’ll stick to mango over pork rinds any day…

'Non-Ketogenic' Low-Carb is Still Too Low

So at higher levels of VO2max, zero-carb diets clearly destroy physical performance in both untrained and trained subjects. But what about less-restrictive carbohydrate-reduced diets - what effect do they have in normal-weight individuals undergoing strenuous exercise?

A study answering this very question was conducted by Helge and colleagues at the University of Copenhagen. During the first seven weeks of this study, one group ate a high-carb diet, the other a low-carb/high fat diet. During the eighth week, both groups ate the high-carb diet. The subjects trained three times a week during the first 4 weeks, then 4 times a week during the last 4 weeks on stationary cycles, at a controlled exercise intensity that ranged between 60 and 85 percent. The workouts lasted 60-75 minutes.

During the first seven weeks, the low-carb/high fat group ate 177 grams of carbs and 217 grams of fat per day. The high-carb group ate 546 grams of carbs and 75 grams of fat per day. Both groups ate similar amounts of protein. While 177 grams of carbs may not typically be considered ‘low-carb’, keep in mind that exercise increases the carbohydrate threshold required to reach ketosis. Indeed, blood ketones rose markedly during the study in the low-carbohydrate group, and were far higher at seven weeks than in the high-carb group.

When time to exhaustion at 81% VO2max was tested at 7 weeks, the high-carb group improved their time by 191 percent, compared to only 68 percent in the low-carb group - a hefty 280 percent difference! After the eighth week, when both groups ate the high-carb diet, the low-carb group managed to improve their time by another 18 percent, but their average time to exhaustion was still much shorter than in the high-carbers[7].

The bottom line is that both zero-carb and low-carb diets are a disaster for those engaged in regular strenuous exercise. And for anyone with a sound knowledge of the biochemistry of energy production, this is no big surprise.

Low-carb diets will kill your cycling performance.

Low-carb diets will kill your cycling performance.

How Muscles Produce Energy, and Other Cool Stuff

Folks, I’m going to give you a very quick primer on how your cells produce energy. It will involve use of some big words, so if your vocabulary is usually limited to short bursts of SMS brilliance like “hey sxy wot u up 2 2nyte?” then try real hard to stick with me here, okay?

Awrighty, let’s start with Adenosine Tri-Phosphate (ATP), the ultimate and immediately usable form of chemical energy for all human work. It is stored in all cells, but like the nitrous in a 9-second drag car it exists only in small and quickly exhausted quantities. When ATP is used for energy, it loses a phosphate molecule and becomes Adenosine Di-Phosphate (ADP). To keep fuelling cellular activity, ADP must be restored back to ATP. There are three pathways for rebuilding ATP from ADP, and the one employed depends on both the intensity and duration of the physical activity.

The first pathway involves breaking down phosphocreatine to obtain phosphate for ATP production. But phosphocreatine is also in limited supply, restricting the usefulness of the ATP-phosphocreatine system to very short duration activities, such as a 10 second sprint, a heavy triple on the bench press, or kicking your back door when your roommates have locked you outside yet again.

The second pathway utilizes glycolysis, which kicks in after phosphocreatine can no longer supply the needed energy. Glycolysis occurs in the absence of oxygen and uses carbohydrate (derived from glycogen and blood glucose) as the fuel source. Glycolytic, or anaerobic, metabolism is limited by the buildup of excess acid in the cell. The 'burn' sensation you feel in your thighs as you run up a hill or perform a twelve-rep set of squats is caused by acid build-up.

The third pathway is the aerobic system, which predominates in low-intensity, longer-duration activities such as walking and jogging. The aerobic system is also the energy system most active at rest. During these activities, enough oxygen can be supplied to the cells via the lungs and bloodstream. This allows for glucose to be broken down completely, hence avoiding the build-up of acid. The aerobic system also relies heavily on fats for energy production. Increased fat use during aerobic exercise occurs as one becomes fitter, if one exercises in a fasted state, or follows a low-carbohydrate diet.

At higher (glycolytic) levels of exercise intensity, however, fatty acids simply cannot be utilized quickly enough to supply the high-energy phosphates needed to create ATP. Only muscle glycogen can meet this need[8]. Glucose is the most rapidly accessible energy source in the body, and muscle glycogen is the most important source of glucose for muscular contraction[9]. Vigorous physical exercise rapidly depletes muscle glycogen and the harder and longer you train, the greater the degree of depletion[10].

Now, if that all left you a little bedazzled, here’s the take-home message: Glycolytic (glucose-dependent) activities will always be glycolytic, because fat simply cannot be processed quickly enough to supply the needed energy. This will not change, ever. If a fat adaptation brainwashee tries to convince you otherwise, they’re essentially trying to rewrite the laws of nature.

Fat chance (excuse the pun).

Muscle Glycogen: A Critical Source of Energy

In contrast to fat, the body can only store limited amounts of glucose. While even very lean individuals still carry several kilograms of body fat, the average 75-kilogram adult only stores around 450 grams of glycogen in their body, most of which is stored in muscle tissue[11]. Successful carb-loading (a practice used by some competitive athletes) can temporarily double this figure, but even under such a best-case scenario, total bodily glycogen stores are still limited. If high intensity exercise is carried on long enough, these glycogen stores are exhausted. If these diminished glycogen stores are not fully restored prior to subsequent exercise bouts, then performance in future workouts will deteriorate.

High intensity cardiovascular exercise (you know, sparring, running fast, riding your bike up steep hills and using it to chase trucks up and down Portrush Road) reduces muscle glycogen stores to a much greater degree than weight training. In controlled studies, muscle glycogen levels typically fall 25-40% in response to a bout of weight training[12,13]. Meanwhile, a single thirty-second sprint can reduce thigh muscle glycogen by a third, while two 30-second sprints can produce a 47% drop (glycogen depletion tapers off significantly after the second sprint)[14-16].

Longer duration cardiovascular exercise, such as marathon running can completely exhaust muscle glycogen stores in a single bout, with depletion occurring more quickly at higher intensities (>70% VO2max) than lower intensities (65% VO2max)[17].

Some of you may be reading this and thinking, “Colpo’s full of it! I train with the weights twice a week, and then do billycart racing every weekend, and a low-carb diet hasn’t hurt my performance. In fact, last weekend I won the Puckston South Inaugural Billycart Championship!”

If this is what you’re thinking, then I have two things to say to you. Firstly, congratulations on your rapid ascent in the glamorous, high-stakes world of billycart racing, your parents must be very proud. Secondly, your overall volume of exercise is quite low and, lucky for you, it is not causing any meaningful degree of glycogen depletion. At least not enough to affect your billycart prowess.

But let’s say you buy yourself a new bike and start riding 2-3 times per week, 2-3 hours at a time. And then one of your buddies convinces you to come along to boxing classes every Thursday night and Saturday morning.

All of a sudden, your training volume has significantly increased. And all of a sudden, you start feeling weaker and more tired. You’re also becoming an increasingly grumpy SOB, shouting at the cat, shouting at other drivers, and shouting at whoever put the toilet roll the wrong way round. The last straw is when your billycart performance starts to flounder.

Dude, eat some carbs, because it only gets worse from here. You’re becoming glycogen depleted, and gorging on all the fat in the world won’t do diddly to correct the situation. You need c-a-r-b-s, the kind found in sweet potatoes, potatoes, taro, white rice, fresh fruits, and other wholesome foods that, contrary to the rantings of the Do-Do-like low-carb gurus (see Part 1) will not turn you into a morbidly obese, insulin resistant tub of adiposity.

But What about Mamo Wolde, Bjorn Ferry and Jonas Colting?

On Planet Earth right now, there are thousands upon thousands of world-class competitive athletes. But when you ask low-carb proponents for some examples of successful low-carbing athletes, they can at best muster three names: Mamo Wolde, Bjorn Ferry and Jonas Colting.

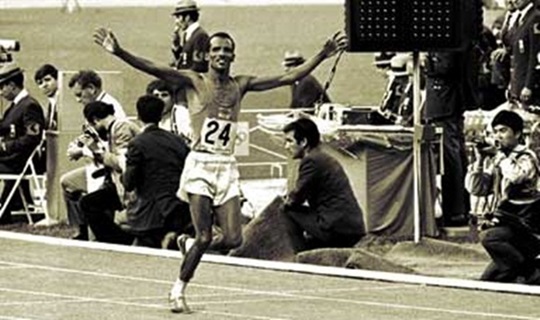

Don't Make False Claims about Mamo, You Momo

The late Degaga (“Mamo”) Wolde was an Ethiopian long distance athlete who won the 1968 Olympic marathon. Do a Google search, and you’ll find Wolde incessantly cited on low-carb websites and forums as proof that low-carb diets are great for serious athletes.

And how exactly did all these folks arrive at the belief that Wolde’s victory at the ’68 games was fueled by a low-carb diet? The source responsible is an article penned by British author Barry Groves, whose website is purportedly devoted to “Exposing dietary misinformation”.

This is what Groves has to say about Wolde’s victory in Mexico City:

“Now let’s look at a real athlete

It was 1968 at the Mexico City Olympic Games. The spectators at the marathon went wild as a relatively unknown Ethiopian, Mamo Wolde, won the marathon. Not only was the thirty-six-year-old runner the oldest man ever to win this prestigious event, he did it in a time that has not been bettered to this day [Anthony’s note: This is incorrect. Wolde’s time was not a record and has been beaten at every Summer Olympics since].

So what was Wolde’s secret?

Wolde grew up in an Ethiopian village. His life consisted of running after and hunting wild game on foot. His diet was one high in animal meat and fat, with practically no carbohydrate. Subsequent tests showed that Wolde’s body, under conditions of physical load, readily burned fat as its main energy source. Wolde had no concept of ‘hitting the wall’. It had never happened to him.”

I have searched high and low to find evidence of Mamo Wolde’s dietary habits during his competitive years, and have found nothing. If Groves has such evidence, he’s not sharing it with his readers. If anyone can confirm Wolde’s eating habits with something of more substance than unfounded conjecture on low-carb websites, I’d love to see it. Just because someone grew up in East Africa and hunted wild game at some point in their life, does not automatically mean they ate like a Masai warrior during their athletic career.

The only evidence Groves appears to cite in support of Wolde’s alleged low-carb ways is a study from a 1994 issue of Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise that had absolutely nothing to do with Mamo Wolde nor with low-carb diets[18]. This study in fact involved six American male collegiate runners whose endurance was tested on three different diets. The amount of fat used for fuel during exercise and time to exhaustion was reportedly increased on the “high-fat” diet. What Groves doesn’t mention is that the composition of said diet was 12% protein, 38% fat, and 50% carbohydrate – hardly the high-fat ketogenic affair he claims, without evidence, that Wolde followed.

This isn’t the first time Groves has cited research that does not say what he claims it does. Back in 2005, when I committed the heinous crime of truthfully stating that calories, not macronutrient ratios, were the final arbiter of fat-derived weight loss, I was besieged by smug low-carbers citing the following passage from Groves’ website:

“‘On a high-fat diet, 4703 to 8471 excess calories were required for each kilogram of added weight. On a low fat VLCD [very low calorie diet], replacing fat calories with 8g/day of equivalent carbohydrate calories reduced weight loss by 1.68kg, corresponding to 3300 calories of carbohydrate/kilogram, possibly 2500 calories per kilogram for carbohydrate alone.’”

Groves then went on to claim that these figures demonstrate a significantly higher amount of calories is required from dietary fat than from carbohydrates to induce the deposition of body fat.

Unlike the cultish followers of the low-carb religion that incessantly quoted this passage all over the Internet, I actually read the paper it was allegedly taken from (Groves referenced it to a 1975 NIH publication titled Obesity in Perspective).

The paper did not contain that quote, and the study in that paper dealt with experimental weight gain, not weight loss! I emailed Groves about this, who subsequently removed the quote from his website. He explained he himself put that quote together – he had taken the weight gain/calorie intake data from the NIH paper, and some fat loss/calorie intake data from a paper published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Needless to say, mixing and matching data from two entirely different studies to create a custom-made quote that supports a pre-conceived conclusion is hardly sound science. If you want to compare the weight loss/gain effects of high versus low carb diets, you do it in the same study among a single sample, the members of which have been randomized to either a high or low carb diet. As I explain in Part 1, and at length in The Fat Loss Bible , when this has been done under tightly controlled metabolic ward conditions, there is no difference in fat-derived weight loss between high- and low-carb groups eating the same amount of calories.

What Elite East African Long Distance Runners Really Eat

Right below Ethiopa in East Africa sits Kenya, another nation known for churning out world class runners. A number of studies have been published detailing just what these elite athletes eat – and it sure as heck isn’t a 100% meat, zero-carb diet.

Mukeshi and Thairu examined the food intake of male Kenyan runners, for two days a week over a 3-month period, and found they consumed an average of 441 grams of carbohydrate daily (8.1 grams of carbohydrate per kilogram of bodyweight, approximately 75% of total caloric intake)[19].

Christensen et al studied adolescent Kenyan runners from the distinct ethnic group known as the Kalenjin. This group, hailing from the Great Rift Valley, produced a staggering 40% of winners of all major international middle- and long-distance running competitions between 1987-1997. The total mean daily carbohydrate intake of the adolescent runners was 476 grams (8.7 g/kg, 71% of total calories). Total intake of protein and fat was 88 and 45 grams, respectively[20].

The most recent study to look at the dietary habits of Kenyan runners also involved Kilenjin athletes. Researchers observed them during a training camp in the North Rift Valley, and found they ate three meals and 2 snacks daily. The staple foods were bread, boiled rice, boiled potatoes, porridge, cabbage, kidney beans, and a thick maize meal paste known as ugali. Meat (mainly beef) was served at the training camp 4 times per week, although the athletes were able to access more meat when at home. Generous amounts of tea (with milk) were consumed throughout the day.

When their intake data was tallied up, it was found that mean daily carbohydrate was 607 grams (10.4 g/kg, 76.5% of calories). Daily protein and fat intakes were 75 and 45 grams, respectively[21].

As it stands, there is no evidence whatsoever that Mao Wolde ate a low-carb diet, and any claim that elite East African runners shatter world records whilst eating nothing but meat and fat is total nonsense.

Mamo Wolde running to victory on what was almost certainly not a low-carb diet.

Mamo Wolde running to victory on what was almost certainly not a low-carb diet.

Bjorn Ferry

Björn Ferry is a gold medal-winning Swedish biathlete who claims to follow a low-carb diet. However, I’ve searched for details on his diet, and found very little. This article discusses a book he has co-authored with his advisor, and according to the English translation: “Ferry will not say it was only dietary change that gave him the gold. There were many factors that played a role.”

So exactly how many carbohydrates Ferry eats is a bit of a mystery. And even if he does follow a low- or even zero-carb diet, that pretty much proves nothing. In fact, given the overwhelming evidence against low-carb diets in the literature, we would be more than justified in suspecting that, if Ferry can succeed on a low-carb diet, he’d do even better on a higher-carb diet.

According to this article, Ferry experienced a lackluster 2009/2010 season. If Ferry upped his carb intake to ensure optimal glycogen stores, maybe his performances would become a whole lot more consistent.

Maybe his mental outlook would improve too, given that both glycogen depletion and low-carb diets have been shown in clinical trials to worsen anger and mood scores[22,23]. After all, this is a guy that "During the 2010 winter Olympics...was quoted saying he would not mind if athletes who use banned substances would get the death penalty or, "at least lots of kicks in the balls.""[24]

Hmmm, sounds exactly like the kind of wonderful, rational, balanced, clear thinking I've come to expect from low-carb devotees. The death penalty for people who kill, maim and torture innocent people? Sure. But for people who use ergogenic drugs?! Sorry folks, but that is certified screwball talk.

Bjorn Ferry's solution to doping in sports: "Kick 'em in the balls and kill the bastards!!" Please don't let this guy enter politics.

Bjorn Ferry's solution to doping in sports: "Kick 'em in the balls and kill the bastards!!" Please don't let this guy enter politics.

(Update June 3, 2013: Since originally posting this article, a couple of Swedish readers have written to assure me Bjorn is actually a nice guy, and nothing like the crazed noose-wielding image his anti-doping comments tend to portray. Also, in response to my recent article debunking the pseudoscientific smack talk of one Danny Albers, one of these readers also reported Ferry has a cookbook with low-carb recipes, which still doesn't tell me a whole lot about the actual diet he follows himself. According to Google’s English translation of his website, Bjorn’s diet is “Swedish, organic and high in fat” which, as I recently noted elsewhere, sure leaves a lot of wiggle room regarding his carbohydrate intake. Lastly, even if Ferry did follow a true low-carb diet leading up to his 2010 victory in the Winter Olympics biathlon, then that pretty much proves...nothing. How would he have fared if he was on a high-carb diet? As I wrote in the Danny Albers article, legendary triathlete Dave Scott won the grueling Hawaiin Ironman not once, but a stunning six times, while following a vegetarian diet. That would seem to be a pretty shining endorsement of vegetarian diets for athletic performance - until one watches the video of Scott reporting how much better and healthier he felt after adding poultry and fish back to his diet. Yep, sometimes athletes succeed in spite of their diets, not because of them...)

Jonas Colting

Jonas Colting is a Swedish athlete who is also cited as following a low-carb diet. However, after winning the Ultraman Hawaii , Colting admitted:

“Between stages I ate non-stop; Recovery drinks, rice pudding, bananas, Clif-bars, candy, chips, water, cookies and some normal meals like Thai food after the first day and fresh fish and mashed potatoes after day 2. My appetite was great all through out and I didn’t have any of that bloating that sometimes occurs during massive physical activity. Except for on the bike during the first day, but I know why that happened.”

When someone pointed this out on a website devoted to the unabashed adulation of all things low-carb, Colting himself replied:

"…you need to put that in context of the event of the Ultraman. It presents physical strains 99.9% of the population will never face and during any kind of event like this, the first priority is to promote digestion.”

Also, as this is an extremely hot and humid event the carbs loads the body on fluids as one gram om [SIC] carb binds four grams of water.

So although I did consume some fast and generally unhealthy carbs I also ate healthy foods and furthermore spent the hundreds and hundreds of days prior to the event maximizing metabolism and health through training and a balanced diet.

I´m not a die-hard low-carb person in every stretch but rather believe in the “train low-race high” concept which includes more carbs during ardous endurance events. None of the negative side effects of excess insulin etc will then occur."

Translation: "I did not eat a low-carb diet. I actually ate a truckload of simple and complex carbs during the event, and my diet leading up to the event was in no way a low-carb diet in the traditional sense. It was in fact a balanced diet featuring a lower-carb content than what is normally adhered to, followed by a high-carb intake prior to and during the event to maintain optimal muscle glycogen levels."

Colting is not a "die-hard low-carb person" because he knows full well that following a true low-carbohydrate diet will ruin his athletic performance.

Jonas Colting: The 'low-carber' who eats quinoa, sports drinks, rice pudding, bananas, Clif-bars, candy, chips, cookies, Thai food and mashed potatoes.

Jonas Colting: The 'low-carber' who eats quinoa, sports drinks, rice pudding, bananas, Clif-bars, candy, chips, cookies, Thai food and mashed potatoes.

Conclusion

Study after study shows that both low- and zero-carb diets are an extremely poor choice for highly active individuals. The best that low-carbers can do to defend their dying fat adaptation hypothesis is to cite a dead Kenyan runner who probably never followed a low-carb diet, a Swiss biathlete whose exact carb intake remains a mystery, and another Swedish athlete who does not follow a low-carb diet but rather a “lower-than-usual-carb” diet during part of the period leading up to a competitive event.

I think it’s safe to say that the evidence in favor of low- and zero-carb diets for athletes is next to non-existent. Do yourself a favour and start listening to real science rather than the performance-destroying pseudoscience spewing forth from the Bizarro world inhabited by misguided low-carb fanatics.

Ciao,

Anthony.

See also:

Sorry Danny Albers, But Low-Carb Diets Still Suck for Athletes!

—

Anthony Colpo is an independent researcher, physical conditioning specialist, and author of the groundbreaking books The Fat Loss Bible, The Great Cholesterol Con

and Whole Grains, Empty Promises.

References

1. Phinney SD, et al. Capacity for moderate exercise in obese subjects after adaptation to a hypocaloric, ketogenic diet. Journal of Clinical Investigation, Nov, 1980; 66 (5): 1152-1161.

2. Bogardus C, et al. Comparison of carbohydrate-containing and carbohydrate-restricted hypocaloric diets in the treatment of obesity. Endurance and metabolic fuel homeostasis during strenuous exercise. Journal of Clinical Investigation, Aug, 1981; 68 (2): 399-404.

3. Phinney SD. Ketogenic diets and physical performance. Nutrition & Metabolism, 2004; 1: 2.

4. Westman EC, et al. New Atkins for a New You: The Ultimate Diet for Shedding Weight and Feeling Great. Fireside, Mar 2, 2010.

5. Phinney SD, et al. The human metabolic response to chronic ketosis without caloric restriction: preservation of submaximal exercise capability with reduced carbohydrate oxidation. Metabolism, Aug, 1983; 32 (8): 769-776.

6. Dr. Coggan's comment was made in a 1995 post on the USENET newsgroup rec.sport.triathlon, which can be accessed here: http://www.rice.edu/~jenky/sports/coggan.html

7. Helge JW. Adaptation to a fat-rich diet: effects on endurance performance in humans. Sports Medicine, Nov, 2000; 30 (5): 347-357.

8. Van der Wusse GJ, Reneman RS. Lipid metabolism in muscle. In Handbook of Physiology. Exercise: Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems. Eds: Rowell LB, Shepherd JT. American Physiology Society, Bethesda, MD: pages 966-967.

9. Groop L, Orho M. Metabolic Aspects of Glycogen Synthase Activation. In: Molecular and Cell Biology of Type 2 Diabetes and Its Complications. Eds: Belfiore F, Lorenzi M, Molinatti GM, Porta M. Basel, Karger, 1998; (14): 47-55.

10. Ahlborg B, et al. Muscle Glycogen and Muscle Electrolytes during Prolonged Physical Exercise. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 1967; 70 (2): 129-142.

11. Olsson KE, Saltin B. Variation in total body water with muscle glycogen changes in man. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, Sep, 1970; 80 (1): 11-18.

12. Haff GG, et al. Carbohydrate supplementation and resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2003; 17 (1): 187-196.

13. Haff GG, et al. Carbohydrate supplementation attenuates muscle glycogen loss during acute bouts of resistance exercise. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, Sep, 2000; 10 (3): 326-339.

14. Esbjörnsson-Liljedahl M, et al. Metabolic response in type I and type II muscle fibers during a 30-s cycle sprint in men and women. Journal of Applied Physiology, Oct, 1999; 87 (4): 1326-1332.

15. Hargreaves M, et al. Muscle metabolites and performance during high-intensity, intermittent exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 1998; 84 (5): 1687–1691.

16. Spriet LL, et al. Muscle glycogenolysis and H+ concentration during maximal intermittent cycling. Journal of Applied Physiology, Jan, 1989; 66 (1): 8-13.

17. O’Brien MJ, et al. Carbohydrate dependence during marathon running. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, Sep, 1993; 25 (9): 1009-1017.

18. Muoio DM, et al. Effect of dietary fat on metabolic adjustments to maximal VO-2 and endurance in runners. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 1994; 26 (1): 81-88.

19. Mukeshi M, Thairu K. Nutrition and body build: a Kenyan review. World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics, 1993; 72: 218-226.

20. Christensen DL, et al. Food and macronutrient intake of male adolescent Kalenjin runners in Kenya. British Journal of Nutrition, 2002; 88 (6): 711-717.

21. Onywera VO, et al. Food and Macronutrient Intake of EliteKenyan Distance Runners. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 2004; 14: 709-719.

22. Keith RE, et al. Alterations in dietary carbohydrate, protein, and fat intake and mood state in trained female cyclists. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 1991 Feb; 23 (2): 212-216.

23. The research regarding low-carb diets and worsened mood outcomes is reviewed here: https://anthonycolpo.com/?p=89

24. 'Swedish biathlon star Bjorn Ferry on doping "Drugs cheats should get the death penalty!"'. Bilde.de. Available online:

http://www.bild.de/news/bild-english/news/swedish-biathlon-star-demands-death-penalty-for-drugs-cheats-11481888.bild.html

Copyright © Anthony Colpo.

Disclaimer: All content on this web site is provided for information and education purposes only. Individuals wishing to make changes to their dietary, lifestyle, exercise or medication regimens should do so in conjunction with a competent, knowledgeable and empathetic medical professional. Anyone who chooses to apply the information on this web site does so of their own volition and their own risk. The owner and contributors to this site accept no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any harm, real or imagined, from the use or dissemination of information contained on this site. If these conditions are not agreeable to the reader, he/she is advised to leave this site immediately.